“A Day in the Life of Daisy the Blouse Maker in 1916”: Storytelling as a Creative Research and Teaching Methodology in Fashion History

by Suzanne Rowland

abstract

The article presents a creative storytelling methodology for working with incomplete research materials where the desired outcome is to understand fashion’s design and manufacturing histories from the perspective of workers on the factory floor. Using an amalgamation of primary research from business archives, oral histories, trade papers, and contemporary fiction, a day in the life of a fictional blouse maker named Daisy is presented here as a short story. Written and continually refined during the process of my doctoral study, Daisy’s story pieces together the process of industrial blouse design and making in the ready-made industry in Britain in the second decade of the twentieth century. Drawing on ideas present in Actor-Network Theory, the maker and her machine form the basis of a conjoined historical ethnographic study. Finally, through pedagogical application, I suggest two approaches for teaching this technique to students to heighten engagement with research, stimulate new avenues of thought, and offer creative enjoyment during the process.

Volume 4, Issue 1, Article 3

Keywords

Storytelling

Story-making

Fashion

Blouse manufacturing

Research

Teaching

Actor-network theory

-

https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040103

-

Rowland, Suzanne. "'A Day in the Life of Daisy the Blouse Maker in 1916': Storytelling as a Creative Research and Teaching Methodology in Fashion History." Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2022, pp. 1-24, https://www.fashionstudies.ca/a-day-in-the-life, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040103.

-

Rowland, S. (2022). “A day in the life of Daisy The Blouse Maker in 1916”: Storytelling as a creative research and teaching methodology in fashion history. Fashion Studies, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.38055/fs040103

-

Rowland, Suzanne. “‘A Day in the Life of Daisy The Blouse Maker in 1916’: Storytelling as a Creative Research and Teaching Methodology in Fashion History.” Fashion Studies 4, no. 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.38055/fs040103.

The idea for writing the story evolved as a way to address the lack of evidence for the daily activities of working-class women’s labour practices in business archives and in company biographies. Blouse company archives are valuable assets for the study of business functions including marketing, managerial actions, property maintenance, equipment purchasing, and legal matters. They were never intended as repositories of the daily lives of workers with their attendant emotions, desires, and disorder. Instead, critical archive studies scholars Anne Gilliland and Michelle Caswell offer the term impossible archival imaginaries to explain how we might construe an archive story where “hoped-for contents are absent or forever unattainable,” importantly stressing that these imaginings are only useful if “drawn into some kind of co-constitutive relationship with actualized records.”[1]

[1] Anne Gilliland and Michelle Caswell, “Records and Their Imaginaries: Imagining the Impossible, Making Possible the Imagined,” Archival Science 16(1) (2016): pp.9-10.

Compiled from fragments of primary research discovered in business archives, advertisements, and editorials featured in trade publications, Daisy’s story is an assemblage of gathered facts and subsequent interpretations of these materials (Figure 2).[2] The purpose of Daisy’s story is to amplify the individual in the mass to understand what her working day was like, and crucially, how a blouse was designed and manufactured on the factory floor. The story is set in 1916 to help understand the role of civilian women making fashionable clothing during the war. Using a traditional beginning, middle, and end scenario, “a day in the life” provides a useful temporal framework for structuring the research.[3] Literary elements, such as the use of diction, syntax, and the names given to “characters” have been informed by the 1911 census, contemporary novels, and oral histories of former factory workers reflecting back on their experiences during the First World War.[4]

It is important to note the limitations of this story. Daisy’s snapshot of her day captures ready-made blouse production in an English town in 1916. While this is reflective of the industry in other industrial towns in Britain, it does not aim to comment on labour practices in the American shirtwaist industry, although it could be used for a future comparative study using Nan Enstad’s research into working class women’s physical, emotional, and cultural experiences as workers in the American shirtwaist industry, ably documented in her book Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, popular Culture, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century.

[2] This method, also known as narrative non-fiction, is used across a diverse range of disciplines, from banking-consumer relationships (Rooney, Lawlor, Rohan, 2016) to ethnography (Narayan, 2007), where it supports a substantial body of literature and methods. Lee Gutkind, founder of the journal Creative Nonfiction, is a significant influence in this area. My storytelling method applies the tools of narrative non-fiction as a historian to fill particular historical gaps and to integrate lived experience of overlooked and sparsely documented garment labourers into the historical record.

[3] Day-in-the-life structures are an established cultural form more formally known as circadian narrative devices. See for example, Annebella Pollen, Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life (London: I. B. Tauris, 2016).

[4] 1911 Census. Novels include Dorothy Whipple, High Wages, (London: Persephone Books, [1930] 2009). Individual oral histories are referenced in footnotes throughout this article.

As an academic research tool, creating a story can spark new ideas as it unites disparate fragments of primary research by inserting emotions and sensory experiences. In highlighting what is known, as well as what cannot be known, but is imagined by the researcher based on empirical experience and informed knowledge, the constructed story offers the researcher a creative and cognitive epistemological method of historical enquiry. Thus initially my aim was not to write a polished final story, but rather to discover and learn during the process of creating the story. This act of “story making” — as speculative designers Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby acknowledge — is a distinct practice to “storytelling” and as such it has the potential to unsettle narratives and liberate new ways of thinking.[5] To clarify, story-making in my practice was the process of research, thinking, clarifying, and the assemblage and re-assemblage of shifting narratives that were always in a flux. Storytelling was the end result of my story-making, the fixed narrative, even if it was only “fixed” for a short while. Thus, storytelling is the overarching term used throughout this article with the understanding that it is both the process and the result.

[5] Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013) 88.

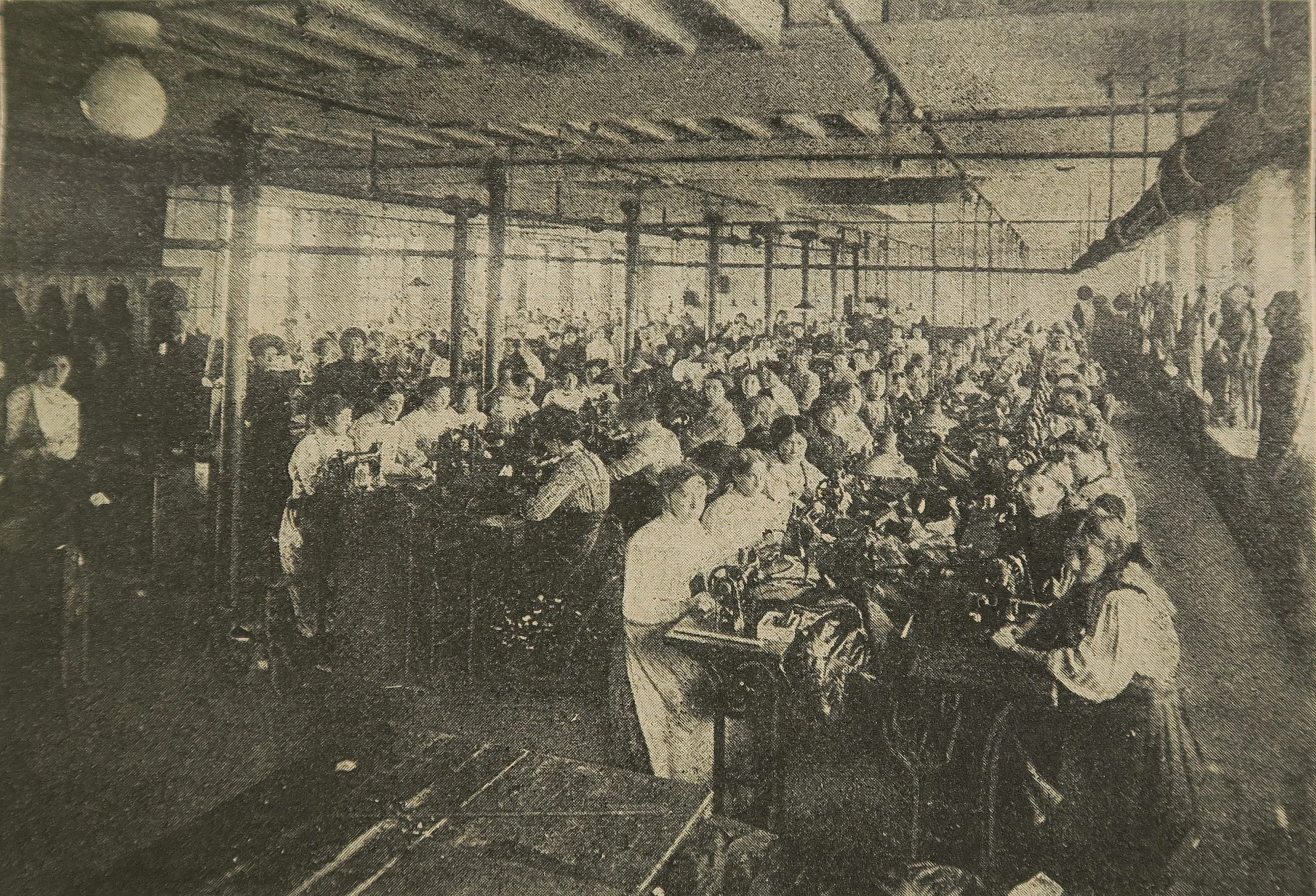

Figure 1

Photograph of 2,500 workers at Corah’s St. Margaret’s Works, Leicester. 350 women worked in a separate blouse factory on the same site. The Drapers’ Record 9 September 2011: iii. © EMAP and the London College of Fashion Archive.

Bruno Latour’s ethnological methodological foundation for researching everyday practices and pursuits is made through first-hand observation of social worlds.[6] For the historical researcher, observations of everyday activities can instead be made through the traces of surviving objects and printed materials. ANT suggests a further way forward through what John Law describes as “story-telling” or “method assemblages.”[7] For Law, emotional and sensory experiences are released through storytelling thus allowing the researcher to connect with the irrational and the non-textual, or “realities enacted in other ways.”[8] In Daisy’s story embodied connections between the human workers and their non-human machines emerge as synchronous and rhythmic motions that enable maximum productivity. We discover, for example, how the designer, who was also the cutter, skilfully manoeuvres her hand-operated mechanical cloth cutter, conscious of not wasting a scrap of cloth to minimize waste and profit loss.[9]

[6] Joanne Entwistle, “Bruno Latour Actor-Network-Theory and Fashion,” Thinking Through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists, eds. Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016) 281.

[7] John Law, After Method: Mess in Social Science Research (London: Routledge, 2004) 122, 126.

[8] John Law, After Method, 97.

[9] The bandsaw, prevalent in high volume ready-made tailoring, proved unsuitable for cutting lightweight blouses. Ideally, for the light silks, crepes and muslins favoured by the blouse industry, handheld cutting machines enabled the operator to cut a lay quickly without manoeuvring the cloth. Cutters in tailoring were usually men. In lightweight blouse making, however, cutters were more likely to be women. During the First World War market leaders the Eastman Machine Company, based in Buffalo, New York, advertised cutting machines suitable for “any girl” to use.

Daisy’s story questions where power lies in the factory. It has long been taken for granted that power and agency resided with entrepreneurs. Countless histories of large corporations and biographies of men of business have informed this narrative. By constructing an alternative narrative, a bottom-up view of history emerges to show how more subtle forms of agency resided with the workers, their machines, and the daily work-related processes they enacted together. As consumers and workers in the British blouse industry — and despite the chaos of the war years — women were vital to the rise of wholesale blouse manufacturing, which grew significantly in the 1910s; and yet their contributions have been unacknowledged. Imagining individual designers, machinists, cutters, packers, and checkers, so essential to production, provide an embodied factory world replete with characters and plot lines. In the rediscovering lost clothing stories through storytelling, the dress historian creates characters like Daisy to stand in for those who are absent. Here the temptation is to create sympathetic personalities that are interesting to work with. In fact, when real people present themselves through memoirs or diaries, as Carolyn Steedman acknowledges, there can be a range of emotions for the researcher from sincere admiration for their politics to irritation at disagreeable traits in their personalities.[10]

Communications scholar Tony Adams notes that in addition to physical experiences, a complex range of emotions is also present for both the researcher and those being studied.[11] How can the researcher of historical subjects reflect on and capitalize on their emotions? One way is to draw on our own experiences, if applicable, while being aware that the legitimacy of adding personal experiences may be called into question if they are not relevant. In Daisy’s story, I used my professional experiences of working with industrial cutting and sewing machinery to compose sensory details, such as the noise in the machine room.[12] Perhaps this connection is understandable because, as Steedman suggests, every historian’s relationship with the archive is personal, inasmuch as individual researchers draw on memories to interpret and construct histories from archival materials.[13]

The story should be read alongside the evidence provided in footnotes.

[10] Steedman’s views on campaigning socialist Margaret McMillan (1860–1931). Carolyn Steedman, Everyday Life of the English Working Class (Cambridge University Press, 2013) 2.

[11] Tony E. Adams, Autoethnography (Oxford University Press, 2014) 11.

[12] As a professional costume maker for film and theatre.

[13] Steedman, Dust, 77. See also Jules David Prown, Art as Evidence: Writings on Art and Material Culture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001) 255.

[14] As Latour explains in ANT research: “The only question one may ask is whether or not a connection is established between two elements […] a network has no outside.” Bruno Latour, “On Actor-Network Theory. A few clarifications plus more than a few complications,” Bruno Latour, blog, 1990.

A Day in the Life of Daisy the Blouse Maker in 1916

At 8:00 AM Daisy began work at William Baker’s blouse factory, knowing she had to work until 9:00 PM that evening to keep up with orders.[15] She already worked six days a week, so extra evening shifts left her feeling exhausted. The military commission for khaki flannel shirts for soldiers had more than doubled the factory’s workload.[16] Nearly half of all blouse makers had been moved onto army shirts. The dull khaki cloth was so tiring for the eyes.[17] Daisy was relieved to still be on blouses. In the long, cramped workroom, she edged down between long rows of sewing machines to find her hard and uncomfortable seat (Figure 2).[18] All machines sat in a line and were all powered from the same source, which sometimes caused problems for the workers.[19] Daisy’s friend Flossie worked in the same section and when her machine broke down last week the whole line of thirty machines had to stop while the fault was repaired. As Mr. Barker, the factory owner, often shouted, “time is money” and so any break in production made Daisy and the others anxious.[20] Daisy’s machine was one of the latest Singer models able to sew 3,500 stitches per minute.[21] To start with she couldn’t get used to the speed so she made a few mistakes and had to unpick her stitching, but now she understood just how much pressure to apply to the treadle. She could not afford to slow down for any reason. Because of the Trade Boards Act, most manufacturers had put their machinists on a basic weekly wage and if they did not earn more than that wage through additional piece work, they were threatened with losing their jobs.[22] Daisy believed this was legalized sweating and had written a letter to the local paper calling for girls to join a union and for all Leicester manufacturers to give workers the advantage of shorter working hours. She signed her letter “ONE OF THE SWEATED” to remain anonymous in case Mr. Baker found out and dismissed her.[23] The threat of dismissal was a daily worry. Mr. Baker even kept a notice pinned to the workroom wall saying any girl with loose hair could be instantly dismissed. Keeping up with the latest fashions wasn’t easy under Mr. Baker’s watchful eye. The girls often shared a copy of their favourite penny weekly Home Chat to look for ideas. Today Daisy wore a fashionable striped blouse with a plain, navy skirt. Hanging on a peg nearby was her best burgundy velour hat with ostrich feather trim — a “copy of a French model” bought from Heringtons’ millinery department.[24]

[15] Overtime slip detailing a blouse maker’s hours as 8:00 AM–9:00 PM, 1916, William Baker uncatalogued archive, Special Collections, De Montfort University, Leicester.

[16] 70% of Leicester manufacturer Corah’s output during WW1 was commandeered for the military. Blouse makers were moved onto army shirts. C. W. Webb, An Historical Record of N. Corah & Sons Ltd. Manufacturers of Hosiery and Outerwear St. Margaret’s Works, Leicester (Leicester: Adams Bros & Shardlow Ltd., 1948) 59.

[17] “Women in the Khaki Trade,” The Queen, 6 March 1915: 387.

[18] Annual Report of the Chief Inspector of Factories and Workshops for the yar 1919 (London: H.M Stationary Office, 1920). House of Commons Parliamentary papers Online. “The stitching trade is […] equipped with seats, although the hard, small pedestal seat, so often supplied for the machinist, cannot be very comfortable.” 78-79.

[19] Line-shaft benching was a group drive system that powered a row of machines concurrently, rather than each machine having an individual power source.

[20] Hilda Marlow recalled how Leicester hosiery and blouse manufacturers Wolsey employed a mechanic with poor skills resulting in repeated break downs. She learnt to fix and maintain her own machine to avoid using him. Some factories would not pay the full basic wage during this waiting time. Oral history, University of Leicester.

[21] Singer’s Class 95-1 model was most commonly advertised as suitable for making blouses. “Class 95-1,” The Drapers’ Record, 13 April 1912: 79.

[22] Letter from “One of the Sweated,” The Leicester Daily Mercury, 10 March. 1911. The Trade Boards Act did not apply to blouse making at this time, which suggests this manufacturer acted illegally by imposing a minimum wage.

[23] Notice from the blouse factory wall, William Baker archive, “On and after this date any girl found working a machine with her hair not fastened up, is liable to be INSTANTLY DISMISSED, March 15, 1905. WILLIAM BAKER.”

[24] Advertisement for Heringtons’ millinery, The Leicester Daily Post, 3 November 1916: 5.

Figure 2

Example of a typical workroom with long rows of machines. “Raven Blouse Room,” The Drapers’ Record, 6 July 1912: 7. © EMAP and the London College of Fashion Archive.

Daisy gathered the pieces to make her first blouse of the day — a smart striped voile design dotted with tiny roses. Each blouse was stitched in the same order — shoulders or yokes (depending on the style), side seams, followed by sleeve seams. Sleeves were inserted next, followed by the cuffs, or sleeve edging. The collar was last. When all machines were in use, the noise was deafening. Daisy felt the physical vibration in her body.

Once Daisy’s first dozen blouses were machined, they were handed to Maud, the new finisher. Fourteen-year-old Maud had recently left school. She struggled to sew curved blouse hems, leaving far too many tucks and gathers for the forewoman’s liking.[25] Despite a fortnight’s tuition on the machine, mostly sewing round shapes on paper, Maud’s machining was not improving.[26] Maud’s hand sewing was not much better. Newey’s metal hooks and bars were sewn on by hand. Luckily for Maud, Newey’s had been commissioned to make gun belts for the soldiers, so made fewer hooks and bars to sew on blouses.[27] Buttons were used more these days, and they were easier to sew. Connie was the buttonholer who operated the noisiest machines in the room. It was also dangerous. The buttonhole was stitched and then a sharp blade sliced the hole open. It’s a wonder Connie hadn’t lost the tips of her fingers. Connie was leaving her job when her fiancé could get leave from the Front so they could marry. Connie’s job was going to the “runabout” Hilda Marlow, who could not wait to leave the drudgery of sweeping the floors and running about for the girls to earn more money as a machine operative.[28]

[25] Poorly sewn hems were observed on many museum blouses and demonstrating how young and inexperienced finishers developed their skills.

[26] Using paper to practice was experienced by a khaki cap maker at Schneider’s garment factory in London, 1914–1919. Jane Cox, “Oral History,” Margaret Brooks, 1975, Imperial War Museum.

[27] “Newey’s,” The Drapers’ Record, 17 July 1915: xx.

[28] Hilda Marlow started work as a “runabout” at Corah’s in Leicester at the age of 14 in 1923. Hilda Marlow, “Interview with Hilda Marlow,” A. Money, 1988, My Leicestershire History, University of Leicester.

At midday the dinner bell rang. The canteen opened and animated talk turned to the latest fashion tips in Home Chat for tulle brimmed hats. Daisy unwrapped bread, marg, and a hardboiled egg brought from home. After half an hour the bell rang again to signal the beginning of the long afternoon shift.

The factory produced medium to best class blouses. This was a reference to the difference in quality of fabric rather than the standard of stitching. Still, Daisy had to sew every blouse to the same high standard. Worryingly, a pair of sleeves in her batch of blouse pieces was warped. Sometimes when one layer of fabric was wrinkled or had a slight fold this happened.[29] Daisy held the sleeves up to show the new Forewoman. She would take them to be recut. The designer, who was also the cutter, was called Miss Downing. She always wore smart flannel blouses with high collars, and a gold watch pinned by a lover’s knot.[30] Miss Downing worked for a London blouse manufacturer for five years before coming to Leicester. Before that she had been a machinist who worked her way up by taking evening classes in drawing and cutting at a trade school.[31] She created one hundred “perfect fitting” new designs for each Spring and Autumn season, sometimes more if there was a special order (Figure 3).[32] The illustrator sketched copies of her designs for the firm’s brochures and for advertising in the trade papers and fashion magazines.

[29] A roller machine was used to layer lengths of fabric, one on top of another, on the cutting table, they were clipped in place and known as a “lay.” If a wrinkle or fold was not spotted during the laying process it resulted in a distorted garment piece.

[30] Dorothy Whipple, High Wages, 22.

[31] The Shoreditch Institute provided training for girls wishing to work in the clothing industries. Clementina Black, The Economic Journal, vol. 16, 1906: 454.

[32] The number of blouses stated in St. Margaret blouse brochures between 1910 and 1919.

Figure 3

“St. Margaret” Blouses for 1916 [detail], The Drapers’ Record, 29 January 1916: xxiii. © EMAP and the London College of Fashion Archive.

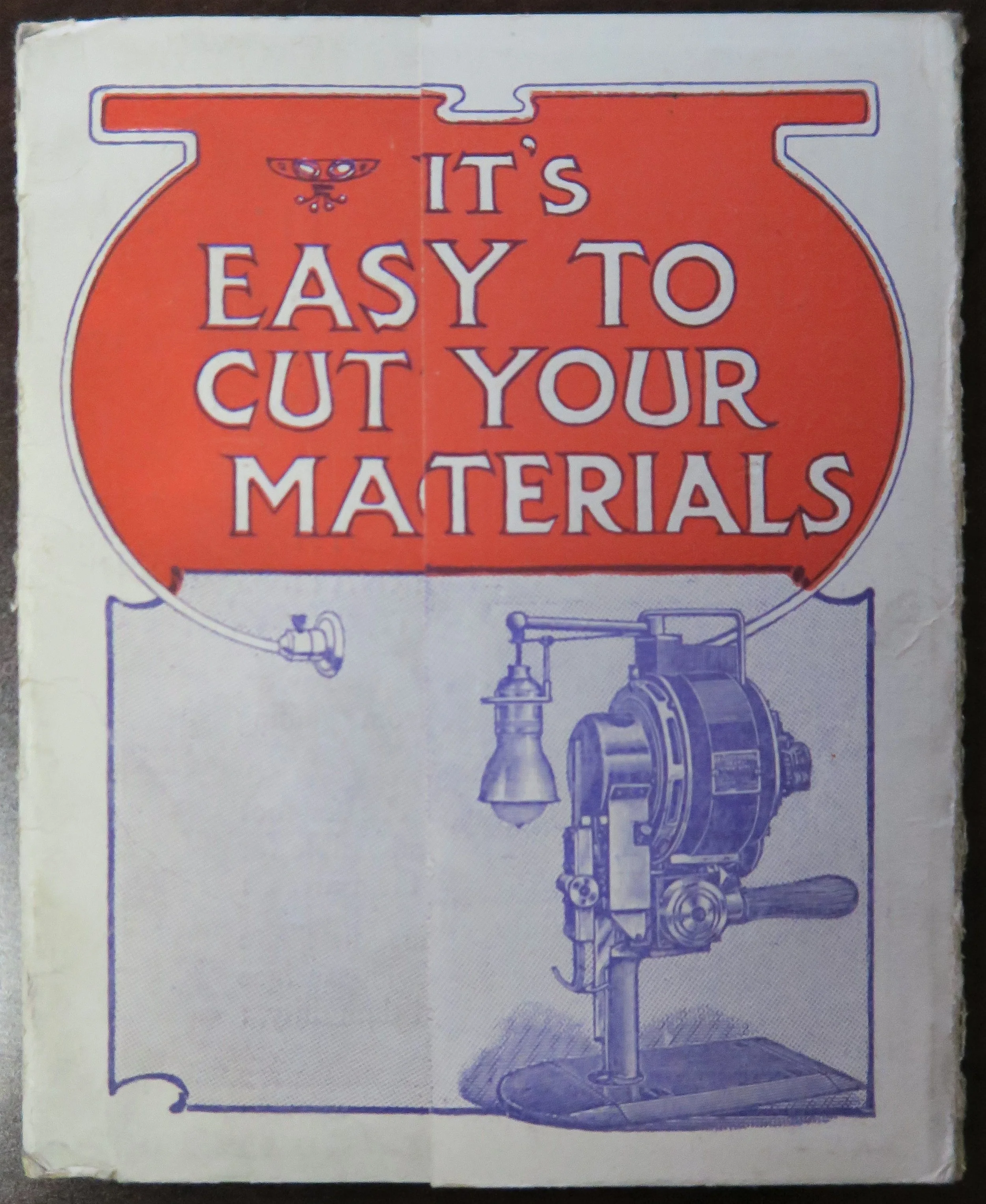

Miss Downing’s small power-machine — the Eastman Cloth Cutting machine — was controlled by a single lever (Figure 4). She said, “any girl can learn how to use it in a few moments.”[33] But Daisy understood that it was a huge responsibility. With up to two hundred layers of fabric to cut through at one time there was always the chance of making a slip and wasting cloth, which of course wasted money. The blade of the machine had to be held upright because any tilting and the sizing of a batch would be out. Mr Baker’s motto, pinned to the factory wall, was “a perfect fit and finish.” Another notice next to it in large print showed exactly what each finished section of the blouse should measure — length of front 22 inches, length of sleeve 19 ½ inches, shaped collar, “2 ¼ inches in front and at back, and 3 inches at side…”[34]

[33] “Cloth and Cost Cutting,” The Drapers’ Record, 26 January 1918: 8.

[34] Factory wall sign, William Baker archive.

Figure 4

Front cover Eastman brochure, “It’s Easy To Cut Your Materials” c.1913. Private archive.

Each batch of a dozen finished blouses were bundled together and dropped in a cart. They were unwrapped, checked, pressed, and folded ready for packing by Winnie.[35] She was meant to pull out rejects, but she knew this resulted in a deduction in the girls’ wages to supposedly cover the cost of the ruined blouse. This was illegal since the Truck Act, but it still carried on at Mr. Baker’s factory.[36]

Blouses were sent to be boxed by Ethel in the packing department. Medium class blouses were boxed by the dozen and the smarter, best class blouses were boxed individually. Then, they were sent down the squeaking conveyor belt to the warehouse where van driver Stanley checked each order was addressed correctly. As petrol was rationed, the van had to be filled to capacity before it could leave, so there was pressure on Daisy and the others to work quickly in the blouse room.[37]

As the long shift drew to a close, Daisy wrapped her woollen shawl tightly around her shoulders, pulled on her velour hat. and walked out into the bitterly cold night air. She felt exhausted and weighed down by the miserable thought of repeating this same day tomorrow, and for days to come until orders had been met and overtime ended.

[35] “Blouses and Robes. Young Lady, to supervise Examining, Ironing, and Folding. &c. Must be capable Controller.” “Situations Vacant,” The Drapers’ Record, 21 August 1915: 282.

[36] Reported criminal trial of a blouse and pinafore manufacturer who forced girls who damaged work, either to purchase the goods or buy replacement material. “The Truck Act,” The Drapers’ Record, 3 March 1917: 460. The Truck Act (1831), amended in 1886 to protect against deductions taken from workers’ wages.

[37] Government monopoly of the railways combined with the requisition of useful lorries made transporting goods extremely difficult for factories. “Transport Troubles,” The Drapers’ Record, 24 April 1915: 149.

Reflections on Daisy’s Story

Daisy’s story performed multiple functions in my research: firstly, it established loose parameters for understanding the process of blouse design and manufacturing, and then it acted as an informal introduction to my PhD thesis, to be referred back to when other forms of research were missing.

Significantly, fashion emerged as a key aspect of Daisy’s everyday life as she and her colleagues were introduced to new blouse designs before they were made available to retailers. As Cheryl Buckley and Hazel Clark acknowledge, “fashion was embedded and contingent in the practices of people’s everyday lives” taking place in familiar spaces, in this case the factory floor.[38] Young women like Daisy understood everyday fashion and, due to an increase in overtime and wages during the war, they had at least some disposable income to buy the cheap ready-made blouses they stitched in the factory. The cross-class appeal of the blouse, especially the ready-made blouses purchased by busy working women, was a key reason for the overall success of the trade in this period.

By creating a social world in the factory, structured into periods of time governed by strict rules, I began to understand how Daisy’s working life was burdened by hidden anxieties. Small setbacks like the breakdown of a machine or a miss-shaped blouse sleeve resulted in the loss of earnings for a worker paid by the piece. There were also lingering threats of dismissal, injury from machinery, or illegal fines for spoilt work. Exhaustion was also evident from long working hours spent sitting on uncomfortable stools in the noisy workroom. Creating a social world with rules and practices embedded in everyday life helped to uncover how vital Daisy’s interaction was with her new highspeed sewing machine. She carried out maintenance and adjusted her seated body to control the machine’s speed for maximum functionality. Time and speed were important facets of everyday life in the factory, as Ben Highmore argues, as this everydayness “is a synchronization based on minutes and seconds.”[39] We see this clearly in Daisy’s story when during the brief lunchbreak hurried discussions turn to the latest millinery fashions in Home Chat. Michel Foucault’s work in Discipline and Punish stresses the factory “as an apparatus for transforming individuals” to adapt to the will of authority.[40] In applying Foucault’s thinking, workers become a homogenous mass lacking in agency.[41] Daisy’s story challenges this narrative by locating the individual within the mass to construct factory life from her perspective. By interpreting Foucault’s later thinking in Technologies of the Self, the agency of the worker is recognized as a way to “transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immorality.”[42] So, although Daisy’s freedom at work was restricted on many levels, she still engaged deeply with fashion. Exposure to new blouse designs potentially influenced and defined her mode of dressing, as did keeping abreast of the latest styles in magazines. By visually signalling tacit sartorial knowledge through her new velour hat and striped blouse, Daisy was rebuffing the subservience expected of her in her working day and instead redefining herself as both fashionable and culturally aware.[43]

[38] Buckley and Clark, Fashion and Everyday Life, 9.

[39] Ben Highmore, Everyday Life and Cultural Theory: An Introduction (London and New York: Routledge, [2002] 2010) 6.

[40] Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin [1977] 1991) 233.

[41] Foucault is criticized for attributing power solely to institutions and not recognizing that it also lies with individuals. Jane Tynan, “Michel Foucault,” Thinking Through Fashion, eds. Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016) 187.

[42] Michel Foucault “Technologies of the Self,” Technologies of the Self, ed. Luther Martin et al. (London: Tavistock Publications, 1988)18.

[43] With reference to Nan Enstad’s claims about American working women’s experiences as consumers of fashion and fiction. Nan Enstad, Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure (New York; Columbia University Press) 50.

Pedagogical Applications of Storytelling

The pedagogical applications of using storytelling to teach fashion’s histories are starting to be explored in new and interesting ways.[44] For example, Sarah Cheang and Shehnaz Suterwalla’s article in Fashion Theory explains that in order to decolonize, challenge, and reframe fashion history, students’ own lived experiences can be drawn upon through the practice of storytelling.[45] Using a range of creative approaches — including zine making and student-led events — Cheang and Suterwalla’s students at the Royal College of Art in London were invited to combine history and theory with their own experiences. In practice, inevitable challenges occurred as students mined difficult and emotional experiences, which involved “a clear responsibility for the group’s wellbeing” for Cheang and Suterwalla as teachers.[46]

[44] See, for example, Dr. Amy Twigger Holroyd’s Fashion Fictions project https://fashionfictions.org/.

[45] They warn however, that “The use of personal experience and lived experience can be used to ask new questions about the familiar if this can be positioned as lived problematics rather than romantic essentialism.”

Sarah Cheang & Shehnaz Suterwalla, “Decolonizing the Curriculum? Transformation, Emotion, and Positionality in Teaching,” Fashion Theory 24:6 (2020): 893.

[46] Ibid.

In my teaching practice I have used storytelling as a pedagogical tool for inciting new thinking in students where research is fractured, and voices are missing. In 2019 I led a workshop entitled “Storytelling as a Research Method” for fellow PhD students at the Techne Congress: Poetics of Method conference at the University of Brighton on the south coast of England. I began by reading Daisy’s story and showing images of my research as evidence for various elements of the story. This was followed by a 45-minute participatory workshop, which focused on creating semi-fictional characters and stories from fragments of the participants own archival research. Using a series of prompt questions, participants were invited to visualize one of the characters inhabiting their research landscape. Working in a lecture theatre with a large group posed many challenges, yet in response, an amazingly detailed story of the day in the life of a domestic servant was shared by one member of the group. Although I was not expecting the re-telling of stories to be an intrinsic part of the process, as this workshop showed, to read aloud and to share storied research with others was a valuable exercise. As social scientist Rob Kitchen argues, storytelling is an “engaging and accessible register for communicating ideas and [providing] a critical lens to reflect society.”[47] Following the workshop, I further developed the list of prompt questions as aid to the story-making process:

Firstly, identify an issue — what do you want to find out?

Find or create a main character. Name them and create a brief backstory.

Find image(s) of your character and of other significant people in their world — you might use existing paintings, anonymous photographs, advertisements, etc.

Who or what else is important? This might be other characters, objects, or events.

Imagine a scenario — this could be a day in the life of one person, or a meeting between two or more people, an interaction with an object, or even a pivotal event.

Imagine a conversation between your key character and someone else — how are they dressed, where are they, what time is it, is anyone listening in…? Think about the atmosphere in the room/sounds/smells/tension/laughter/silences… How do they interact with their surroundings?

What happens next?

How does your story end?

Reflect on your findings. Has this method helped you discover something previously hidden?

What were the limitations of this method? What do you still want to discover?

[47] Rob Kitchen, “Writing Fiction as Scholarly Work,” Blogs.LSE.ac.uk 11 Dec. 2011:1.

I further developed this idea for a workshop called “Re-constructing Fashion Histories through Storytelling” in 2021 for first year undergraduates at Rose Bruford College of Theatre and performance, situated on the outskirts of London.[48] Using a collection of black and white photographs of anonymous sitters purchased from antique shops and online retailers and dating from c.1890 to1920, I set students a series of tasks using autoethnography as a methodology for relating to and understanding what was being worn (Figure 5).[49] The idea was to build a general picture of everyday clothing practices in this period by inviting students to reflect on the decisions they made when getting dressed on that particular day. Based on Lynda Barry’s engaging ethnographic approach presented through her creative sketchbooks, the students were asked to answer a series of questions by writing in full sentences.[50] This involved imagining they were a character or an observer in the image and describing their surroundings. Further details were required, including adding sensory perceptions when describing details of clothing — smells, textures, and colours. As with Barry’s work, sketching, doodling, and list making were suggested as part of the creative process.[51] The second half of the workshop required students to layer these descriptions with contextual details taken from primary sources. Old Bailey court records online and online newspaper archives provided storylines and background details. Hard copies of weekly women’s journal Home Companion, dating from 1912, provided fashion references (Figure 6). Here, students could find, for example, an advertisement for a John Noble fashionable “Tailor-Cut,” gored, serge skirt, available in cream, navy and black.[52] In practice, contemporary references to attitudes to the body, unusual treatments for ailments, and recipes for unfamiliar foods were amongst the most popular findings which added an element of fun to the research process.

Participants were invited, if comfortable, to read their stories aloud. At the end of the session, students completed a survey so that we could all assess how useful, or not, the session was to their studies, and how likely they are to use it in future fashion history research. A comments box enabled a broader range of thoughts and ideas. Here, comments ranged from the enthusiastic “I was surprised how my story flowed and I had so much more to say” to the less enthusiastic “interesting but not personally my cup of tea.” On reflection, the workshop required more time than the constraints of a one-off session allowed. Nevertheless, I am grateful to the students for their generous participation and for advancing my thinking. As Cheang and Suterwalla concur, in reshaping the teacher/student relationship “we can listen and learn from each other in our efforts to also listen better ourselves.”[53]

[48] With thanks to Dr Veronica Isaac for inviting me to deliver this workshop.

[49] For an explanation of the process of autoethnography and a broad range of applications see Tony E. Adams, Autoethnography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[50] Lynda Barry, What it is (Montreal, Quebec: Drawn and Quarterly, 2008) 143-146. Cited by Tony E. Adams, Autoethnography: 76.

[51] Barry, What it is: 76.

[52] “Graceful Designs,” Home Companion, 15 June 1912: ii.

[53] Cheang & Suterwalla, “Decolonizing the Curriculum?,” 896.

Figure 5

Black and white photograph of 5 unknown sitters, c.1912. Author’s collection.

Figure 6

Front cover Home Companion, 15 June, 1912. Author’s collection.

Conclusion

The workshops and ideas presented in this article are put forward in the hope that they will contribute to a dialogue in fashion studies and dress history that embraces storytelling as an additional way into academic research and interpretation.[54]

Using story-making, or the broader termed “storytelling” as a creative research method — as Dunne and Raby acknowledge — engages the imagination in what they term “thought experiments” to not only approach problems in unique ways but to hopefully find enjoyment in the process.[55] As an enjoyable and creative outlet for the historian of fashion, creating a non-fictional narrative can be a welcome contrast to the more formal aspects of academic writing, even though, as Kirin Narayan admits: “The word ‘enjoyable’ almost seems guiltily at odds with the professional duty that presses us forward.”[56] For my writing practice, on days when I had writer’s block, spending time revising Daisy’s story was often a first “warm-up” step into academic writing.

To write for the self, as if no one will read what is being written, is arguably a liberating experience. Yet, as I discovered through my teaching practice and through re-telling Daisy’s story as a way of communicating the crux of my PhD to others, to realize the full potential of the story it should be shared and read aloud. As a method for research and for teaching there is still much to discover as Narayan’s conclusion suggests:

As ethnographers, we are usually trained to set forth arguments, rather than to write narrative. We learn to use illustrative anecdotes, but not how to pace our representations of events to hold a readers’ interest. As we seek ways to craft narratives from field work materials, it is useful to remember how stories gain power by piquing our basic curiosity about what happens next.[57]

Hopefully, this brief investigation of storytelling as a method for both research and teaching has offered something new to fashion studies and historians of fashion. This method has potential to enable practice-based fashion students from diverse educational and geographical backgrounds to connect contextual histories and critical theories and with their studio practice. For researchers, it has potential to unlock silent voices that have been marginalized, forgotten, or ignored.

[54] See Dr Amy Twigger Holyroyd’s project “Fashion Fictions” for an alternative creative method of storytelling https://fashionfictions.org/.

[55] Dunne and Raby Speculative Everything: 80.

[56] Kirin Narayan, “Tools to Shape Texts: What Creative Nonfiction Can Offer Ethnography,” Anthropology and Humanism, 32:2 (2007): 141.

[57] Ibid.

Bibliography

Adams, Tony E. Autoethnography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. Book.

Alexander, Lynn. M. Women, Work, and Representation: Needlewomen in Victorian Art and Literature. Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2003.

Black, Clementina. The Economic Journal (1906, voll. 16): 454.

Buckley, Cheryl and Clark, Hazel. Fashion and Everyday Life: London and New York. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Cheang, Sarah and Suterwalla, Shehnaz. “Decolonizing the Curriculum? Transformation, Emotion, and Positionality in Teaching.” Fashion Theory (2020): 879-900.

Enstad, Nan. Ladies of Labour, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

Entwistle, Joanne. “Bruno Latour: Actor-Network-Theory and Fashion.” Rocamora, Agnès and Smelik, Anneke. Thinking Through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists. London, New York: I.B.Tauris, 2016. 269-284.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin, [1977] 1991.

Foucault, Michel. “Technologies of the Self.” Martin, Luther. Technologies of the Self. London: Tavistock Publications, 1988.

Gillibrand, Anne and Caswell, Michelle. “Records and Their Imaginaries: Imagining the Impossible, Making Possible the Imagined.” Archival Science (2016): 53-75.

Highmore, Ben. Everyday Life and Cultural Theory: An Introduction. London, New York: Routledge, 2002.

Kitchen, Rob. “Writing Fiction as Scholarly Work.” 11 December 2011. Blogs.LSE.ac.uk. Web. 16 January 2021.

Latour, Bruno. “On Actor-Network Theory. A few clarifications plus more than a few complications.” 1990. Bruno-latour.fr. 28 January 2020.

Law, John. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London: Routledge, 2004.

Narayan, Kirin. “Tools to Shape Texts: What Creative Nonfiction Can Offer Ethnography.” Anthropology and Humanism (2007): 130-144.

Pollen, Annebella. Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life. London: I.B. Tauris, 2016.

Raby, Anthony Dunne and Fiona. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013.

Rooney, T, Lawlor, K, Rohand, E. “Telling Tales; Storytelling as a methodological approach in research.” The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods (2016): 147-156. Web.

Rowland, Suzanne. “The role of design, technology, female labour, and business netwroks in the role of the fashionable, lightweight, ready-made blouse in Britain, 1909-1919.” University of Brighton, 2021.

Steedman, Carolyn. Dust. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001.

—. Everyday Life of the English Working Class. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Tynan, Jane. “Michel Foucault: Fashioning the Body Politic.” Agnès Rocamora, Anneke Smelik. Thinking Through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists. London: I.B. Tauris, 2016. 184-199.

Webb, C.W. An Historical Record of N. Corah & Sons Ltd.,. Leicester: Adams Bros & Shardlow Ltd, 1948.

Whipple, Dorothy. High Wages. London: Persephone Books, [1930] 2009.

Acknowledgements

For generous support in the creation of this article, thanks to Dr. Veronica Isaac, Professor Annebella Pollen, and my PhD supervisors Dr. Charlotte Nicklas and Dr. Damon Taylor at the University of Brighton. I am grateful to the students who participated in my workshops and taught me so much about the process of storytelling.

Author Bio

Dr. Suzanne Rowland is a lecturer in fashion and dress history in the School of Humanities and Social Science at the University of Brighton.

She is a member of the university’s Research Interest Group Tailoring for Women 1750–1930 and was organizer of the two-day online conference held in September 2021 entitled Women’s Tailored Clothes Across Britain, Ireland, Europe and the Americas, 1750–1920. Her AHRC/Design Star funded doctoral thesis, completed at the University of Brighton in March 2021, addressed the role of design, technology, and women’s labour in the rise of wholesale blouse manufacturing in Britain, 1909–1919. She is a committee member of 19th Century Dress and Textiles Reframed, and current Chair of the Association of Dress Historians Awards Sub-Committee (2020–2022).

Article Citation

Rowland, Suzanne. "'A Day in the Life of Daisy the Blouse Maker in 1916': Storytelling as a Creative Research and Teaching Methodology in Fashion History." Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2022, pp. 1-24, https://www.fashionstudies.ca/a-day-in-the-life, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040103.

Copyright © 2022 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)