A Radical Alternative: Pursuing Size Inclusivity in the Indie Sewing Community

By Chloe Numbers

DOI: 10.38055/FS050104

MLA: Numbers, Chloe. “A Radical Alternative: Pursuing Size Inclusivity in the Indie Sewing Community.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-29, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050104

APA: Numbers, Chloe (2024). A Radical Alternative: Pursuing Size Inclusivity in the Indie Sewing Community. Fashion Studies, 5(1), 1-29. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050104

Chicago: Numbers, Chloe. “A Radical Alternative: Pursuing Size Inclusivity in the Indie Sewing Community.” Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2024): 1-29. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050104

Volume 5, Issue 1, Article 4

Keywords

Sewing

Indie sewing

Fat fashion

Size-inclusive fashion

Crafting

abstract

For those with underrepresented and misrepresented bodies, the ready-to-wear fashion industry has long been a frustrating and disappointing space to navigate. Though size inclusivity has been a topic of concern in the fashion space in recent years, the size ranges available at most fashion brands are very limited. Finding clothes remains frustrating and exhausting for people outside of a narrow spectrum of body types that exist within the privileged fashion ideal. Attempting to dress sustainably and ethically complicates dressing even further. In contrast to the ready-to-wear industry, businesses within the independent (or “indie”) home sewing community have consistently and earnestly improved in areas like size inclusivity, body positivity/radical self-acceptance, sustainability, and distribution of free information and education. In recent years, many of these small businesses have successfully and efficiently executed successful size expansion projects. As a result, options for sewists with larger bodies have rapidly increased, and there is a higher community standard for size inclusivity. I propose that the indie sewing pattern community exists as a “radical alternative” to the ready-to-wear industry, in that it offers community members an opportunity to opt out of the ready-to-wear fashion sphere in favour of participating in a more inclusive and progressive fashion system.

Introduction

Within the last decade, extended sizing options at ready-to-wear fashion brands have noticeably increased as the fashion industry creeps its way towards progress. More models with conventionally underrepresented bodies are featured in marketing content and on runways, and brands have introduced extended sizes to their collections. While this increase of representation and the wider variety of options for underrepresented bodies in ready-to-wear spaces are positive steps, there is still a tremendous amount of change that is necessary before the ready-to-wear fashion industry is engaged beyond the surface of inclusivity. Individuals of minoritized identities, including fat people, racialized people, disabled people, and people with otherwise non-normative bodies, continue to be systematically underserved by the ready-to-wear fashion industry.[1] Beyond the scope of body and access inclusivity, the environmental impacts of fast fashion, greenwashing, and opaque business practices within the fashion system present additional barriers to those hoping to dress sustainably.[2]

Since the mid-2010s, home sewing has experienced a thunderous revival.[3] The ubiquity of social media apps, YouTube, and blogging platforms has not only sparked interest in sewing by increasing visibility, but has also made sewing skills more accessible through the efficient dissemination of free information.[4] Through eschewing fast fashion options in favour of handmade garments, home sewists have built a thriving virtual community. Independent sewing pattern designers have prioritized size inclusivity in their pattern collections, which in turn increases the amount of individuals who are able to use these patterns to create well-fitting, stylish, and more eco-conscious garments. In this niche online creative space, home sewists and independent sewing pattern designers are creating radical solutions and movement towards progress.

[1] Peters, Lauren Downing. “You are What You Wear: How Plus-Size Fashion Figures in Fat Identity Formation.” Fashion Theory 18, no. 1 (2014), 48.

[2] Muenter, Olivia. “Fast Fashion Is Bad for the Environment. For Many Plus-Size Shoppers, It’s the Only Option.” Refinery29, November 20, 2021. https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2021/11/10781654/plus-size-fast-fashion-ethics.

[3] Bain, Jessica. “Darn Right I’m a feminist…Sew what?” the Politics of Contemporary Home Dressmaking: Sewing, Slow Fashion and Feminism.” Women’s Studies International Forum 54, (2016), 57.

[4] Russum, Jennifer Ann. “From Sewing Circles to Linky Parties: Women’s Sewing Practices in the Digital Age.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2016, 56

The intention of this project is to evaluate the state of the online independent sewing community in regards to the resources available to home sewists, how this community has spearheaded inclusivity and progress, and what steps could be taken to further this progress. This evaluation focuses specifically on an examination of size-inclusive indie sewing pattern companies, as well as exploring the tactics and strategies employed by these businesses to increase size inclusivity in their pattern collections. I argue that the indie sewing community exists as a “radical alternative” to the mainstream ready-to-wear fashion industry. “Radical alternative” in this context is defined as a means of voluntarily absenting oneself from a conventional system in favour of an alternative system that is fundamentally more progressive and inclusive. Members of the indie sewing community have the ability to substantially opt out of the ready-to-wear fashion space, as they are able to participate in a radically alternative system in order to dress themselves and participate in fashion in a significantly more progressive way.

The virtual nature of the online sewing community and PDF sewing patterns (the format of choice for most independent designers) affords individuals from around the world access to these products and this community. As I am primarily an English-speaker, this project is geologically oriented around evaluating companies and community spaces based in English-speaking regions, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

I am approaching this topic as a community member, and from a position of familiarity. As a woman living in a large body, clothes shopping has long been a source of trauma rather than a source of joy.

I was inspired by the idea of making clothes to fit my body rather than trying to fit my body into the limited and insufficient options provided by the mainstream fashion industry. Like many home sewists, I began to build upon the basic machine sewing skills I had acquired in childhood, with the goal of crafting a new wardrobe that met my own standards for style, fit, quality, and sustainability. Access to sewing patterns that were available in my size played a crucial role in this journey.

In my personal experience, the opportunity to sew my own clothes using well-drafted, proportionally graded sewing patterns from independent pattern designers gave me the power not only to control the style, fit, quality, and sustainability of my clothes, but also the power to choose when and how I participate in mainstream fashion spaces. In this way, the online community that these designers work within and serve with their patterns function as a radically alternative option to the mainstream, ready-to-wear fashion system.

Fauntly Foundations: The History of Sizing Systems and Pattern Grading in Ready-to-Wear Fashion

Fashion scholars widely acknowledge that the ready-to-wear fashion industry is currently, and has been historically, exclusionary.[5] Fat bodies have been marginalized in fashion spaces since the inception of ready-to-wear manufacturing in the mid-nineteenth century.[6] The industrialization of ready-to-wear fashion significantly changed the way in which larger individuals, and women in particular, were able to engage with the fashion system. Until this point in time, women would source their clothing from professional dressmakers or sew their own clothes.[7] The links between the thin ideal, the segregation of fat bodies in the fashion space, and the technology of clothing manufacturing can be traced to fundamental flaws in the ready-to-wear industry of the early-twentieth century.[8] The advent of ready-to-wear fashion resulted in a shift from reliance on bespoke garments specifically made for a particular body’s shape to mass-manufactured options based on standardized size charts.[9] Paolo Volonté explains in Fat Fashion that this reversal of the relationship between dress and the body reinforced the importance of bodily dimensions to a body’s fashionable status:

As mass production of clothing advanced, it became possible to think that body dimensions are important, that they are a key aspect of physical appearance and beauty, that they can be compared, and that it is necessary to be concerned with them. The standardization of clothes entails the standardization of bodies, and this is the condition for a standard based on size, such as thinness, to be raised to the state of a bodily ideal to be pursued.[10]

Research and analysis on these early standardized size charts demonstrate how the historical marginalization of fatness in fashion can be traced back to numerical data. In Lisa Hackett and Denise Rall’s 2018 article “The Size of the Problem with the Problem of Sizing: How Clothing Measurement Systems have Misrepresented Women’s Bodies, from the 1920s to Today,” the authors argue that “western” sizing charts were not initially created with the general population in mind, that they have historically been and continue to be inconsistent, and that they have not evolved alongside the societies that they exist in.[11]

In the United States, for instance, some of the earliest sizing surveys that were used to inform standardized sizing charts were conducted at Smith College, Vassar College, and the Pratt Institute. The data compiled in these surveys was not representative of a wide spectrum of body types, considering the participants were mostly affluent, thin, young, white women.[12]

[5] Volonté, Fat Fashion: The Thin Ideal and the Segregation of Plus-Size Bodies, 20.

[6] Keist, “How Stout Women Were Left Out of High Fashion”, 26.

[7] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 1.

[8] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 121.

[9] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 1.

[10] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 12.

[11] Hackett and Rall, “The Size of the Problem with the Problem of Sizing: How Clothing Measurement Systems have Misrepresented Women’s Bodies, from the 1920s to Today”, 263.

[12] Kidwell, Claudia and Christman, Margaret, Suiting Everyone: The Democratization of Clothing in America, 108. Quoted in Peters, “Flattering the Figure: Fitting In”, 170.

Early sizing charts were informed by numerical data based on the bodily measurements of survey participants, and the patterns from which clothing is cut and sewn are also based on these bodily measurements and ratios. Patterns and pattern blocks have been used in a variety of forms for both the mass manufacture of clothing, in bespoke dressmaking, and in home sewing, dating back to at least the eighteenth century.[13] In the context of mass manufacturing, pattern grading processes have prioritized thinner bodies for economic and efficiency reasons. Ideally, for manufacturers, a pattern used for ready-to-wear, size-standardized clothing will be based on one initial pattern block. For each size in a given size chart, the pattern would be scaled up or down according to a mathematical algorithm.[14]

Historically, there was no singular mathematical standard for how pattern blocks were graded and sized; rather, manufacturers developed their own processes, independently and without cohesion.[15] In the early-twentieth century, the majority of clothing manufacturers used a base pattern block with a 36-inch bust, with proportionally graded bust and hip measurements. Commonly called the “perfect 36” within the industry, this pattern block was a physical manifestation of bodily ideals within pattern making. The “perfect 36” pattern block system led to an increasing amount of fit issues that emerged as patterns were scaled from the initial block.[16] Early ready-to-wear clothing manufacturers attempted to scale patterns using complex proportional theories, but these theories did not accurately account for the ways in which larger bodies change shape.[17] This process meant that achieving a precise fit for all consumers seeking to buy ready-to-wear clothing in a standardized size was virtually impossible.[18] At a certain point, size grading from the “perfect 36” would fail to accommodate certain bodies. As these technological limitations in pattern grading resulted in a strong incentive to limit the number of sizes produced, the thin ideal was reinforced in early ready-to-wear fashion manufacturing.[19]

[13] Moore, Jennifer Grayer. “A Brief History of Patternmaking”, 15. In Patternmaking History and Theory, edited by Jennifer Grayer Moore , 11–30. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

[14] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 131.

[15] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 145.

[16] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 116.

[17] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 116.

[18] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 116.

[19] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 132.

This continues in modern manufacturing, where initial pattern blocks are usually designed between a size zero and size four. This block will then be scaled using automatic and digitized grading techniques.[20] The scaling limits of this system reach to about a size twelve or size fourteen; after this limit, larger sizes begin to suffer from grading inaccuracies if a larger pattern block is not introduced into the system.[21] This requires additional time, funds, and attention to detail, which impacts the profitability of mass-manufactured fast fashion.[22]

Early critics of this system included stoutwear manufacturer Albert Malsin, co-founder of plus-sized fashion brand Lane Bryant.[23] As early as the 1910s, Maslin criticized how size standardization techniques were not functional for producing clothing for larger women.[24] Maslin, along with other members of the Associated Stylish Stout Wear Makers, proposed multiple alternative sizing algorithms that could be used to properly grade large-sized clothing, known as “stoutwear.” Though members of this association endeavoured to use their expertise to manufacture well-fitting garments for larger women, Peters explains in “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder” that stoutwear manufacturers often used the shortcomings of the “perfect 36” sizing system to promote their own “scientific” solutions for fitting larger bodies.[25] In this way, the fat body was continually commodified and framed as a problem in need of an advanced solution, even by the stoutwear industry’s own advocates.

While the stoutwear industry of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries provided a variety of options for ready-to-wear clothing for women with larger bodies, these options were designed to intentionally make the wearer appear as thin as possible. In her research on the stoutwear industry, Peters describes that stoutwear discourses “were underpinned by a slenderness imperative’” that both prioritized and idealized thinness aspirations.[26] The relationship between stoutwear and the “slenderness imperative,” as described by Peters, is reflective of how early ready-to-wear options for “average” sized women and larger women differed both in what was available for purchase and in how the garments were conceived of and designed.

[20] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 132.

[21] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 131.

[22] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 132.

[23] Keist, “The New Costumes of Odd Sizes”, 34.

[24] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 131.

[25] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 118.

[26] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 1.

Though often problematic in nature, the discourses of the early stoutwear industry existed specifically because there was such an industry that provided ready-to-wear clothing options for larger women. In fact, in the early twentieth century, fat women actually had multiple choices when considering where to purchase clothing. As hostility towards fatness grew through the 1920s and 1930s, the economic impact of the Great Depression led to the decline of the stoutwear industry. It would be several decades until extended-size garments re-emerged as an influential topic of discussion in “western” fashion spaces, and the segregation of plus-sized bodies in the fashion system was reconsidered in a significant capacity.[27] [28]

Historical Background: Home Sewing and Indie Patternmakers

Home sewing has experienced a widespread revival over the past decade. In response to this revival, scholars have begun to map the reasons why home sewing is experiencing a surge in popularity at this moment in time.[29] In her 2016 article “‘Darn Right I’m a feminist…Sew what?’: the Politics of Contemporary Home Dressmaking: Sewing, Slow Fashion and Feminism,” Jessica Bain argues that the resurgence of home sewing is not an example of post-feminist retreatism; rather, it is a nuanced and complex example of domestic revival as a demonstration of discursive activism, feminism, and democratized access to fashion.[30]

Home sewing, once considered an essential skill for women, underwent a significant transformation in the mid-nineteenth century when access to domestic sewing machines dramatically reduced the time it took to sew a garment.[31] In the 1860s, the introduction of commercial sewing patterns allowed for the creation of much more complicated garments. Around this time, four sewing pattern companies– Butterick, McCall’s, Vogue, and Simplicity– began selling paper patterns, and thus, the home sewing pattern industry was born.[32] Although the home sewing industry was significantly impacted by the rise of the ready-to-wear clothing industry, it was common for women to sew clothing for themselves and their families through the 1960s and into the 1970s.[33] The high prices of ready-to-wear clothing, as well as apprehension about the quality of ready-to-wear, kept home sewing alive and well in “western” homes.

[27] Peters, “Stoutwear and the Discourses of Disorder”, 360.

[28] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 145.

[29] Bain, Jessica, “Darn Right I’m a feminist…Sew what?”, 57.

[30] Bain, Jessica, “Darn Right I’m a feminist…Sew what?”, 58.

[31] Martindale, Addie. “Home Sewing Transformed: Changes in Sewing Pattern Formats and the Significance of Social Media and Web-Based Platforms in Participation”, 149. In Patternmaking History and Theory, edited by Jennifer Grayer Moore , 149–162. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

[32] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 150.

However, in the mid-1980s, gradually decreasing prices and increased access to ready-to-wear fashion eventually made purchasing clothing more cost-advantageous than sewing it at home.[34] Home sewing became less popular and sewing pattern companies faced economic challenges as a result. Multiple buyouts and mergers amongst the “Big 4” sewing pattern companies changed the landscape of the dwindling home sewing space. Marketing efforts emphasized sewing for crafts, Halloween costumes, and home decór projects, instead of for garment sewing.[35] Some independent pattern companies began to emerge in the 1980s and 1990s, providing small collections of specialty patterns for maternity and nursing clothes, heirloom children’s styles, and specialty clothing niches like equestrian wear and folkwear.[36]

It was not until the advent of the internet that sewing experienced a significant increase in popularity. In the 2000s and throughout the 2010s, the internet enabled low-cost and easily accessible sewing training through classes and tutorials, which dramatically lowered the entry barriers for home sewing education.[37] The internet has also allowed for online sewing spaces to form across geographic barriers, fostering the social connections within sewing communities.[38] This form of social engagement has been identified by Addie Martindale as a crucial factor in the resurgence of home sewing.[39]

Martindale notes in “Home Sewing Transformed” that these online communities have been the key to continued participation in home sewing.[40]

[33] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 150.

[34] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 150.

[35] Emery, Joy Spanabel. “New Challenges: 1960s–1980s”, 188. In A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The Home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution, 178–194. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

[36] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 150.

[37] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 151.

[38] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 153.

[39] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 154.

[40] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 156.

Access to well-fitting clothing options is perhaps the most significant factor in the home sewing resurgence. In a 2018 study published in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Addie Martindale and Ellen McKinney evaluated the decision processes of women who had the option of purchasing or sewing their own clothes.[41] The repeated sentiment that resulted from this study was the ability to exercise control over the way garments fit one’s body. Dissatisfaction with the fit of ready-to-wear clothing is described as a “key reason” for why women continued to choose sewing over shopping. Participants of all sizes, including those with larger bodies, reported that ready-to-wear options did not fit their bodies well.[42] As explained in the previous section, the sizing systems of the modern ready-to-wear fashion industry were born of a fundamentally flawed pattern grading process that inherently privileged bodies with measurements close to a “bodily ideal.” When one has the ability to choose a sewing pattern that is adjusted to fit their body size, they are empowered to reject ill-fitting ready-to-wear options in favour of garments that fit their body more accurately and more comfortably.

In a similar study conducted by Martindale and McKinney in 2018, home sewists expressed that sewing their own clothing enabled them to present themselves in a more authentic and desirable way.[43] Improved garment fit was a critical control factor to nearly every woman who participated in the study, and the desire to have properly fitting clothing was a universal reason for sewing participation amongst those surveyed.[44] Martindale and McKinney also reported that survey participants cited four main factors in how sewing allowed them to exercise control over their appearance: the amount of clothing sewn, control over the styles of clothing, quality control, and fit control.[45] Martindale and McKinney concluded that the information gathered in this survey established notable benefits to home sewing, as it increased participant’s satisfaction with their appearance and their self-presentation to the public.[46]

[41] Martindale, Addie and Ellen McKinney. “Sew Or Purchase? Home Sewer Consumer Decision Process.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 22, no. 2 (2018), 176

[42] Martindale & McKinney, “Sew Or Purchase? Home Sewer Consumer Decision Process.”, 183.

[43] Martindale, Addie & McKinney, Ellen, “Exploring the inclusion of home sewing pattern development into fashion design curriculums”, 556. (2018) International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 11:1.

[44] Martindale & McKinney, “Exploring the inclusion of home sewing pattern development into fashion design curriculums”, 567

[45] Martindale & McKinney, “Exploring the inclusion of home sewing pattern development into fashion design curriculums”, 569.

[46] Martindale & McKinney, “Exploring the inclusion of home sewing pattern development into fashion design curriculums”, 574.

Independent pattern designers are another major contributing factor to the current resurgence of home sewing. In contrast to the vast majority of “Big 4” patterns, “indie” pattern companies usually offer their patterns in a PDF format (in addition to traditional paper patterns, which some indie designers continue to produce). PDF sewing patterns allow instantaneous access to purchased patterns, as the tiled format files can be printed and pieced together at home.[47] Indie pattern designers are also known for providing detailed instruction booklets, which often contain pictures or drawings of each step in the sewing process, in-depth instructions and tops, and thorough cutting instructions provided in both metric and imperial measurements.[48] In contrast, Martindale notes that traditional instruction booklets found in “Big 4” patterns are much more sparse, and that these instructions are difficult to understand for beginner sewists.[49] Martindale also notes the increased access to pattern designers, who often make themselves available on social media platforms and through contact forms on their websites. This access to the designer provides opportunities for questions about the patterns, pattern adjusting and alterations, and sewing advice.[50]

This existing research on home sewists and the virtual sewing community demonstrates how members of the online sewing community experience benefits from increased access to low-cost educational resources, stylish and accessible sewing patterns, control over garment fit and construction, and engagement with other sewists who share common interests.[51] Independent designers are perceived as being engaged with their customers and community members, who are invested in creating quality and accessible patterns that meet the needs of home sewists.[52]

Existing Resources

The indie sewing community as a whole has prioritized size inclusivity as a standard expectation for businesses in this space.[53] Building on Dr. Bain’s theorizations on the home sewing resurgence, I argue that the online indie sewing community is reclaiming access to fashion in a way that is radically alternative to forced engagement with a problematic fashion system. While size inclusivity has received more attention in the fashion industry in recent years, the fashion industry remains highly problematic in regard to fatness and accessible extended-size clothing options. In the spring of 2022, Vogue Business published its size inclusivity report on Fashion Week from the autumn/winter 2023 season. Out of 9,137 looks from various designers across 219 shows held in New York, London, Milan, and Paris, 0.6% were plus-size (US 14+), 3.8% were “mid-size” (US 6-12), and 95.6% of looks presented were worn by models wearing a size US 0-4. Throughout the season, only 17 brands featured one or more “plus-sized” looks.[54] Though the designer fashion space represented at Fashion Week is notoriously exclusive when it comes to body diversity, these statistics are reflective of the continuing discrimination against those with non-normative bodies in the fashion industry. Fatness continues to be marginalized as something ugly and undesirable, and body size continues to be weaponized as a barrier that prevents larger people from accessing and engaging with fashion.[55] It is commonly believed by those involved in the plus-sized fashion space that plus-sized clothes are lacking in aesthetic quality; namely, they are not ‘“fashionable.”[56] Poor quality in design, poor quality in materials, and poor fit are some of the most frequently noted deficiencies in ready-to-wear plus-size clothing options.[57] In contrast, fat sewists, who are otherwise excluded from the slim-centered ideal of the mainstream fashion industry, are enabled to subvert these obstacles by making their own clothes.[58]

Independent pattern company Muna and Broad is an excellent example of a radically alternative option. Since its debut in 2019, Muna and Broad has led the sewing community in size inclusivity, intentional design, and community access. Dr. Leila Kelleher and her business partner, Jess,[59] started Muna and Broad with the intention of creating sewing patterns specifically for fat bodies, with a size range that begins where many other pattern companies’ size ranges end. Dr. Kelleher, who is the patternmaker and drafter for Muna and Broad, has served as an Assistant Professor of Fashion Design and Social Justice at Parsons School of Design since 2022. With a PhD in Functional Movement and a focus in studying how different bodies move and function, Dr. Kelleher’s expertise deeply informs the patternmaking process for fat bodies.[60]

[47] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 159.

[48] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 159.

[49] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 159.

[50] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 159.

[51] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 162.

[52] Martindale, “Home Sewing Transformed”, 158.

[53] Note: ‘Size-inclusive’ is an imperfect term, as true size inclusivity is rarely possible. Superfat and infinifat people, for example, are regularly unable to access options that are labeled as “size-inclusive.”

[54] “The Vogue Business Autumn/Winter 2023 Size Inclusivity Report.” Vogue Business. March 13, 2023.

[55] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 143.

[56] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 141.

[57] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 145.

[58] Bain, Jessica, “Darn Right I’m a feminist…Sew what?”, 60.

[59] Jess has not publicly disclosed their last name.

[60] Kelleher, Leila, & Jess. “About Us”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.munaandbroad.com/pages/about.

Muna and Broad patterns are currently offered in a size range that covers a 40-64" bust and 41.5-71.5" hip. If a sewist has measurements that are larger than the covered size range, Muna and Broad will grade any of their patterns up to that sewist’s custom measurements at no extra cost.[61] In theory, this approach can be considered the only way to be truly and completely size inclusive, as any set size range is inherently exclusive of those who measure outside of the largest available size. As Calla Evans notes in “You Aren’t What You Wear: An Exploration into Infinifat Identity Construction and Performance through Fashion,” fashion options “drop off dramatically for women larger than a US dress-size 28 and become almost non-existent for those who are a size 32 or larger.”[62] A customization option allows anyone who falls outside of a given size range to still access the product in a size that fits their body.

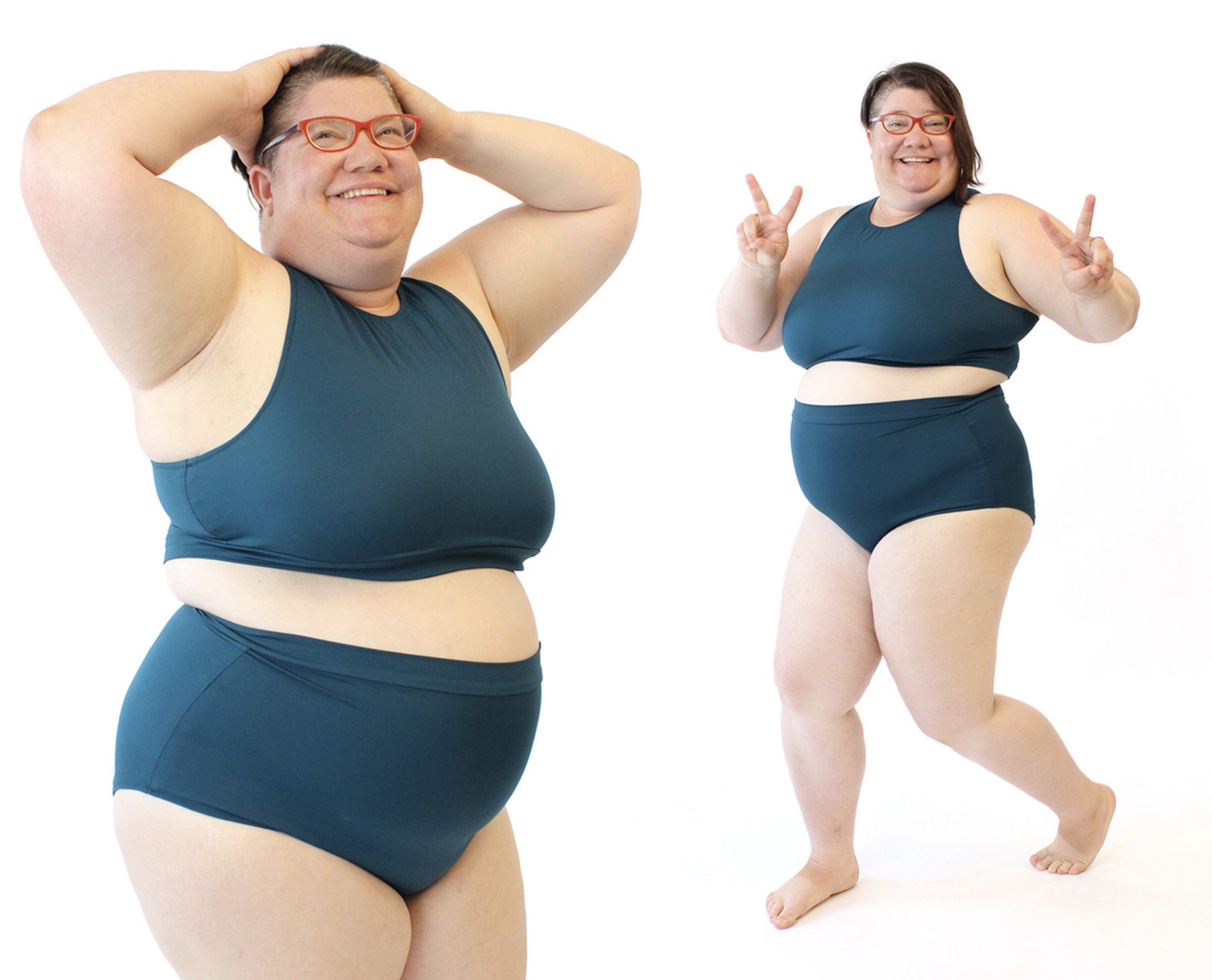

All Muna and Broad pants patterns are drafted specifically to account for an overhanging belly shape, which reduces the need for fit adjustments in this area (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In contrast to most other pattern companies, which grade patterns from one or two pattern blocks, Muna and Broad use a new block for every few sizes.[63] This close attention to detail and fitting mechanics caters to the specific fit needs of larger bodies, which scale according to different proportions from smaller bodies.[64] As a result, sewists who may need to make multiple adjustments to patterns scaled up from a much smaller pattern block will likely be able to utilize Muna and Broad patterns without making several adjustments.[65] This simplifies the sewing process, and makes the Muna and Broad patterns more accessible to beginner sewists who may not yet have the necessary skill set to make complex fit adjustments. A service like Muna and Broad’s, that not only centres but specifically caters to the unique shapes and needs of fat bodies, stands in stark opposition to the experience of ready-to-wear shopping for fat customers.

[61] Kelleher, Leila, & Jess. “Additional Sizes: Grading up our Patterns for you”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.munaandbroad.com/pages/custom-grading-for-larger-sizes.

[62] Evans, Calla. “You Aren’t What You Wear: An Exploration into Infinifat Identity Construction and Performance through Fashion.” Fashion Studies 3, no. 1 (2020), 3.

[63] Kelleher, Leila, & Jess. “Our Sizing”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.munaandbroad.com/pages/our-sizing.

[64] Volonté, Fat Fashion, 131.

[65] Kelleher, Leila, & Jess. “Our Sizing”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.munaandbroad.com/pages/our-sizing.

Figure 1

Product Photograph for Kapunda Undies Sewing Pattern, Muna and Broad. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www.munaandbroad.com/collections/frontpage/products/kapunda-undies-sewing-pattern-pdf.

Figure 2

Product Photography for Noice Jeans Sewing Pattern, Muna and Broad. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://www.munaandbroad.com/collections/frontpage/products/noice-jeans-sewing-pattern-pdf.

Sew Outdoorsy, founded by indie pattern designer Claire Birnie, also offers a custom sizing option for those who fall outside of the size range offered by the pattern company. Sew Outdoorsy patterns are offered in sewing sizes 14-42, with a size range that covers hips measuring 46"-73". Sewists with hips larger than 73" can have their patterns professionally graded by Birnie for no extra cost.66 Sew Outdoorsy is unique, in that it offers patterns for specialty technical wear. Birnie reflected on her motivations for starting her pattern company in episode 214 of the Love to Sew podcast:

It was completely born of a need for myself. I’m a very fat person. I have a 62 inch hip, and I’m at the top end of most indie patterns. And obviously, I enjoy sewing for myself and sewing clothes. And I have a great range of designers now I can choose from, but there was nothing for my hobby…so I thought, if no one else is [gonna] do it, be the change you want to see.67

Further in her interview with the Love to Sew podcast, Birnie explained that designing plus-size patterns for hiking clothes necessitates special attention to waistband construction, room in the abdomen and thighs, and overall ease (the amount of room left between a garment and one’s body), because fat bodies move and morph differently than slim ones when moving actively.68 In this way, Birnie constructs her patterns to cater specifically to maximize comfort and utility for fat body shapes. This is an example of how indie pattern designers can improve upon the traditional and faulty pattern grading methods that are utilized by ready-to-wear brands.

66 Birnie, Claire. “Home Page”. Sew Outdoorsy, 2023. “https://www.sewoutdoorsy.co.uk/.

67 Wilkinson, Helen & Somos, Caroline, hosts. “Episode 241: Sew Outdoorsy with Claire Birnie,” September 23, 2023, in Love to Sew, producers Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos, podcast, MP3 audio, 59:00, https://lovetosewpodcast.com/.episodes/episode-241-sew-outdoorsy-with-claire-birnie/.

68 Wilkinson, Helen & Somos, Caroline, hosts. “Episode 241: Sew Outdoorsy with Claire Birnie,” September 23, 2023, in Love to Sew, producers Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos, podcast, MP3 audio, 59:00, https://lovetosewpodcast.com/episodes/episode-241-sew-outdoorsy-with-claire-birnie/.

Figure 3

Product Photograph for Auburn Blazer Sewing Pattern, Cashmerette. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://www.cashmerette.com/products/auburn-blazer-pdf-pattern.

Indie company Cashmerette also specializes in sewing patterns for fat bodies, with a specific focus on those with larger breasts (Figure 3). The first page of the Cashmerette website states, “We empower sewists with big boobs to create a dream wardrobe that actually fits.”69 In 2015, founder Jenny Rushmore launched Cashmerette with a size range covering sizes 12-30 and cup sizes C-H.70 In 2021, Cashmerette expanded their size range to cover sizes 0-32. Rushmore recently authored Ahead of the Curve, a sewing book that teaches the intricacies of perfecting fit for larger bodies and breasts.71 Cashmerette’s specific focus on patternmaking for bodies with larger breasts is an example of how indie sewing pattern companies often cater to body types that are underrepresented in mainstream fashion. For instance, Closet Core Patterns’ size 14-32 block specifically caters to “pear-shaped” bodies.72 Cashmerette patterns often include separate pieces specifically designed for both larger hips/backsides and fuller abdomens, offering further options for customization and fit.73

Rushmore is also one of the founding members of the Curvy Sewing Collective, an online platform dedicated to fostering community for plus-sized sewists and addressing the issues and challenges they often face. The Curvy Sewing Collective website contains a comprehensive list of pattern companies that sell plus-size patterns, as collections of community resources, book lists, fitting tutorials, educational blog posts, and pattern reviews.74

69 Rushmore, Jenny. “Cashmerette: Sewing for Curves.” Cashmerette, 2022. https://www.cashmerette.com/.

70 Rushmore, Jenny. “Cashmerette: Sewing for Curves.” Cashmerette, 2022. https://www.cashmerette.com/.

71 Rushmore, Jenny. Ahead of the Curve. London. Quadrille by Hardie Grant, 2021.

72 Lou, Heather. “Size Chart.” 2022. https://closetcorepatterns.com/pages/size-chart.

73 Rushmore, Jenny. “How to Choose your Pelvis Fit in Cashmerette Patterns”. October 14, 2020. https://blog.cashmerette.com/2020/10/how-to-choose-your-pelvis-fit.html.

74 Rushmore et. all. “Curvy Sewing Collective.” Curvy Sewing Collective, 2022. http://curvysewingcollective.com/.

A similar community can be found within the Fat Sewing Club, which describes itself as “A radical fat corner of the sewing Instagram.”75 In addition to managing the aforementioned Instagram account dedicated to fat sewists and their experiences, the Fat Sewing Club maintains a collective blog written by fat sewists from the community. A recent blog post shared on the Fat Sewing Club blog, titled “Help Wanted: Plus Size People Need Adaptive Clothes Too” by author Val L., addresses the need for more adaptive sewing patterns. Val writes:

This is my plea to plus sized pattern drafters, adaptive clothing pattern drafters and ready to wear adaptive clothing brands: We are here. We need to be clothed. We deserve to be included. We deserve comfortable, easy to wear and stylish clothing. I can’t survive a Canadian winter in an oversized cotton-polyester housedress.76

In their post, Val detailed various ways in which adaptive clothing differs from non-adaptive clothing, and concludes with a call to action for indie pattern designers to incorporate more adaptive options into their pattern lines. There are currently some, albeit limited, options for specifically adaptive sewing patterns. For example, Rad Patterns, an indie pattern company with patterns for both adults and children, offers a line of intentionally adaptive patterns covering sizes XXS-6X.77 These patterns are designed with features such as access points for breastfeeding and devices like feeding tubes and insulin pumps, adaptive closures and openings, alterations for wheelchair use, and adaptations for limited arm mobility.78

75 Fat Sewing Club, Instagram. Accessed April 2, 2022. https://www.instagram.com/fatsewing.club/

76 L., Val. “Help Wanted: Plus Size People Need Adaptive Clothes Too.” Fat Sewing Club, 21 May 2021, http://fatsewing.club/. Accessed 1 Apr. 2022.

77 Thiel, Stephanie. Rad Patterns, 2022. https://www.radpatterns.com/about-me/.

78 Thiel, Stephanie. Rad Patterns. “Category: Accessible”. 2022. https://www.radpatterns.com/about-me/.

In another Fat Sewing Club blog post titled “What fashion school didn’t teach me: Learning to ‘see’ fat beauty,” author Ruby Gertz details her personal frustration with finding clothes to fit her body. Gertz, founder of the pattern company Spokes & Stitches, sells gender-neutral sewing patterns in two expansive fit shapes, with a size range covering a 30"-75" hip. On their website homepage, Spokes & Stitches encourages potential customers to opt out of fast fashion by sewing their own clothes.79

Gertz credits online indie sewing spaces like Fat Sewing Club and Curvy Sewing Collective with helping her to heal from the toxic and fatphobic culture she experienced in fashion school, as well as helping her to form a more loving relationship with her own body. In response to the fatphobia she experienced in the fashion industry, Gertz writes:

But if the root of our cultural reverence for thinness is capitalism, and it is now common knowledge that there is a massive chunk of the population that wants garments and sewing patterns in larger sizes, why aren’t designers eagerly throwing themselves at this white space in the market? Does fatphobia prevail over making money?

Gertz concludes her post with the statement: “It’s true that we weren’t taught to ‘see’ fat beauty, but we can now choose to teach ourselves. And it is possible, if you are willing, to retrain your eye and recalibrate your perspective. And fat liberation benefits everybody, no matter what size you are.”80

Gertz’s negative experiences in the fashion industry are heavily substantiated by research and evidence. Plus-sized fashion design is, more often than not, simply not taught to students. A 2015 study by Jeffrey Mayer, professor of Fashion Design at Syracuse University, could not identify a single dedicated design course for plus-sized clothing at any fashion design program worldwide.81 Likewise, textbooks focused on plus-sized fashion design are extremely rare, and often outdated or out of print.82 Those that do exist are driven by a “slenderness imperative” strategy, where the objective of the designs is not to create fashionable apparel but clothing that aims to make the wearer appear as small as possible.83

79 Gertz, Ruby. “Spokes & Stitches: Sewing Patterns for Solarpunks”. Spokes & Stitches, 2022 https://spokesandstitches.com/.

80 Gertz, Ruby “What fashion school didn’t teach me: Learning to “see” fat beauty.” Fat Sewing Club, February 5, 2021. http://fatsewing.club/.

81 Pipia, Alexa. “The push for plus: How a small part of the fashion industry hopes to make big changes to the plus-size women’s fashion market.” (2015). Cited in Fat Fashion by Paolo Volanté, pg. 152.

82 Volanté, Paolo. Fat Fashion: The Thin Ideal and the Segregation of Plus-Size Bodies. Bloomsbury, 2022. 152.

83 Peters, Lauren Downing. “Flattering the figure, fitting in: The design discourses of stoutwear, 1915-1930.” Fashion Theory 23, no. 2 (2019). 187.

Though mainstream fashion brands have made marginal improvements in their extended size offerings in the past several years, ready-to-wear fashion remains far from size inclusive. Shoppers who wear above a size 22 are frequently unable to access the plus-sized lines that popular brands have introduced, as the size options have only marginally increased, often only to a 2X or 3X.84 Evans explains, “Clothing options for bodies in the small to mid-fat range continue to increase at a rate that is disproportionate to any increase in options for those in the super to infinifat range.”85 Companies that do offer plus-sized lines often fail to offer access to their plus-sized options as effectively as they do with their straight-sized offerings, with many retailers only offering their plus-size options online. Retailers that do offer plus-sized options in-store lack effective geographical distribution, as urban brick-and-mortar stores rarely stock plus-sized options, which are relegated to more rural and less accessible locations.86 Volonté notes that “regular-size fashion brands that do make plus-size lines to sell in their own stores…never display plus sizes in their windows and may end up shunting them to low-visibility nooks…where stocks may not be replenished often.”87 Though size inclusivity has begun to gain traction in the ready-to-wear fashion industry, the mainstream fashion sphere remains sizeist and highly size exclusive.

While even the largest independent home sewing pattern businesses are dwarfed in comparison to ready-to-wear conglomerates, they have been more proactive and effective in making progress towards size inclusivity in their businesses. In the indie sewing space, online discussions about the need for substantial size range improvements among pattern companies escalated on a community-wide scale in 2018. At this point in time, some pattern companies had already spearheaded expansion processes. Megan Nielsen Patterns, one of the original independent online sewing pattern companies, announced in June of 2018 that they had started expanding their patterns to sewing size 30 with the launch of their new Curve size band.88 Once online discussions around size inclusivity reached a fever pitch in late 2018/early 2019, several other indie pattern brands heeded to the community’s call for increased size inclusivity and began to launch their own size expansion projects.89

84 Tullio-Pow, Sandra, Kirsten Schaefer, Ben Barry, Chad Story, and Samantha Abel. “Empowering Women Wearing Plus-Size Clothing through Co-Design.” Clothing Cultures 7, no. 1 (2020;2021;): 102.

85 Evans, “You Aren’t What You Wear”, 11.

86 Volanté, Paolo. Fat Fashion, 155

87 Volanté, Paolo. Fat Fashion, 156.

88 Nielsen, Megan. “Introducing Extended Sizing.” Megan Nielsen Patterns, June 29, 2018. https://blog.megannielsen.com/2018/06/introducing-extended-sizing/.

89 Sewcialists blog.”Curvy Sewing, One Year Later: Where Are We Now?” Sewcialists, February 21, 2020. https://thesewcialists.com/2020/02/21/curvy-sewing-one-year-later-where-are-we-now/.

Helen Wilkinson, founder of Helen’s Closet Patterns, announced in November of 2018 on the company’s blog page that they would be expanding their size range to a women’s sewing size 30.90 Wilkinson cited the progressive nature of the sewing community as a motivating factor for this decision, along with her own experience of becoming “plus-sized” as an adult. She wrote:

Am I really at the top end of the size range in stores? Am I really the end of the line for fashion?... shopping in 90% of stores isn’t even an option anymore. When I look in the mirror, I just see a person. A 30-year-old woman, who, for reasons baffling to me now, can’t go into a store and buy a pair of pants.91

Preliminary research on the demographics of sewists who would use the extended size range was done in the form of a detailed survey which Wilkinson called the “Curvy Sewing Survey.” The results of the survey were quite thorough, providing data compilations on height, measurements, body shapes, cup sizes for sewists with breasts, ready-to-wear size averages versus sewing size, body descriptor preferences, and sizing terminology preferences.92

Wilkinson compiled the data from the survey into multiple graphs and charts, so that the information could be easily shared with and interpreted by the sewing community. Throughout the survey data, Wilkinson included blog sections in which she made multiple commitments regarding the quality of the size expansion operation. These commitments included scaling and grading the expanded sizes proportionally to minimize fit problems commonly found in ready-to-wear garments, ensuring that every size in the updated size range was tested by a sewist of that size.93 Wilkinson also committed to prioritizing models with underrepresented bodies in her product photos. The Helen’s Closet Curvy Sewing Survey was initially compiled in January of 2019, and within 18 months, Helen’s Closet had re-released all existing patterns in the updated size range, as well as several new patterns.94 As of April 2022, Helen’s Closet Patterns has further extended their size range up to size 34 (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and has also updated the language used in all pattern materials to be gender-neutral.95

90 The author of this article was employed at Helen’s Closet Patterns, Inc. in 2019, as the company initially expanded its size range.

91 Wilkinson, Helen. “Curvy Sewing Survey Results”. Helen’s Closet Patterns, January 25, 2019. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/.

92 Helen’s Closet Patterns, “Curvy Sewing Survey Results.”

93 Helen’s Closet Patterns, “Curvy Sewing Survey Results.”

94 Helen’s Closet Patterns, “Curvy Sewing Survey Results.”

95 Wilkinson, Helen. “Introducing the Jackson Tee and Pullover”. Helen’s Closet Patterns, January 22, 2021. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/.

Figure 4

Product Photograph for Cameron Button Up, Helen’s Closet Patterns. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/product/cameron-button-up/.

Figure 5

Product Photograph for Sandpiper Swimsuit, Helen’s Closet Patterns. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/product/sandpiper-swimsuit/.

Following suit, independent pattern designer Friday Pattern Company expanded their size range in 2019.96 Friday Pattern Company’s expanded size range is one of the widest offered by indie sewing pattern companies, covering sizes XS-7X, or from a 34"-63" hip. Friday Patten Company has also embraced gender-neutral fashion options and currently offers two intentionally gender-neutral sewing patterns (Figure 6 and Figure 7).97

Helen’s Closet and Friday Pattern Company are representative examples of companies that paved the way in the indie sewing space by proactively providing size ranges for sewists who require options outside of those typically covered by ready-to-wear brands.98 As a result, the standard for size inclusivity was raised in this niche community, and larger sewists now have expanded access to high-quality, intentionally designed, and graded sewing patterns. While the ready-to-wear fashion space has experienced an “increased buzz” surrounding size inclusivity, this “buzz” should be viewed with suspicion, as it is often market-driven rather than driven by a genuine desire to be inclusive.

As Volonté explains, “the various recent cases of fashion ‘opening up’ to fat bodies should rather be regarded as marketing episodes in a fairly stable context.”99 In contrast, these small home sewing businesses have genuinely put in the work to make their products permanently more inclusive.

96 Gurnoe, Chelsea. “Expanded Size Range Update.” Instagram, March 21, 2019. hhttps://www.instagram.com/p/BvSpkXfnG9a/.

97 Gurnoe, Chelsea. “Friday Pattern Company.” Friday Pattern Company, 2022. https://fridaypatterncompany.com/.

98 As of fall 2023, other pattern companies with partial or complete size ranges up to at least size 30 include (but are not limited to) Closet Core Patterns, Megan Nielsen Patterns, By Hand London, Grainline Studio, True Bias, Paper Theory Patterns, Artist Patterns, Sew Liberated, Sew House Seven, Rad Patterns, Chalk and Notch Patterns, House Morrighan, Seamwork, Itch to Stitch, Daughter Judy Patterns, Sew DIY Patterns, Charmed Patterns, Unleashed Patterns, and Tilly and the Buttons.

Figure 6

Product Photograph for Ilford Jacket, Friday Pattern Company. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://fridaypatterncompany.com/products/the-ilford-jacket-pdf-pattern.

Figure 7

Product Photograph for Elysian Bodysuit, Friday Pattern Company. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://fridaypatterncompany.com/products/elysian-bodysuit-pdf-pattern.

Becoming Radically Alternative: What Can Improve?

Designers like Helen Wilkinson and Chelsea Gurnoe consistently manage to accomplish well-researched, data-driven, highly tested size expansions with far fewer resources than those available to ready-to-wear fashion brands. Therefore, the indie sewing space could currently be categorized as radically alternative.

There is still room for further progress towards a more impactful radical alternative in the indie sewing space. Several well-intentioned pattern companies are simply too small to have the financial resources required to produce patterns covering as wide a size range as more prominent pattern companies do. Pattern companies that do have extensive size ranges are still limited to a certain capacity, as individuals with body measurements above a pattern’s largest size will remain excluded from their size range.

As the indie sewing space is perpetually community-minded, a community resource-sharing system could be developed to help these smaller companies, which often only have one employee making patterns outside of their full-time jobs, expand their size ranges to be more inclusive. This could involve creating a financial fund that larger companies contribute to on a regular basis through a percentage of pattern sales, which would then be redistributed to support smaller companies. Moreover, more pattern companies with the resources to do so could adopt the custom grading policy employed by Muna and Broad and Sew Outdoorsy, and offer free pattern grading to fat sewists who are outside of their size ranges. Pattern companies should respond to the call made by Val L. in her piece for Fat Sewing Club and work with disabled sewists and/or disabled fashion consulting resources to develop adaptive patterns or free adaptive expansion packs for their existing products. As customization is inherent in the act of sewing, creating adaptive solutions is a tangible and achievable way that indie sewing pattern designers can continue to increase inclusivity in the community.

Sewing influencer Samantha, who advocates for increasing accessibility in sewing and crafting spaces, suggested in an interview with the Love to Sew podcast that sewing pattern designers can make patterns more adaptable by using visual representations of how garments fit on models who utilize mobility aids on their packaging and in their marketing materials.100 Samantha states in the interview:

A lot of people with disabilities using wheelchairs or mobility aids, they already know…adaptations they need to make for their patterns. So it’s things like they want the top to be more cropped so that when they’re in the wheelchair, it’s not bunching across the tummy…it’s not necessarily making adaptations to the patterns, but it’s also showing the patterns on people with disabilities as well. If you’re…not using a disabled model, including seated photos, that’s a key part of accessibility.101

Figure 8

Product Photograph for Marie Dress, By Hand London. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://byhandlondon.com/products/marie-shirt-dress-pdf-sewing-pattern-uk-2-38.

While some pattern companies, like By Hand London, are already using product images showing disabled sewists who use mobility aids (Figure 8), other companies could prioritize hiring disabled models to increase representation in their marketing materials. Pattern companies could also include more imagery of seated models, as Samantha suggests. In addition to making product photos more adaptable and useful for disabled sewists, seated photos can help fat sewists to discern how garments will fit their bodies in seated vs. non-seated positions.

While the indie sewing community is generally very welcoming to Trans individuals and the LGBTQIA+ community, the aesthetics of indie sewing patterns trend significantly feminine. Pattern designers could invest more resources into designing patterns with more “gender-neutral” and masculine aesthetics. This lack of masculine-oriented patterns results in men having fewer options to choose from should they decide to pursue utilizing indie patterns to sew their own clothes.

It must also be acknowledged that garment sewing is no longer a ubiquitous skill, and that many people simply will not have the time to learn to make their own clothing. While access to sewing education resources has vastly improved over the last several years, the attributes of this community’s efforts towards size inclusivity cannot be utilized by those who are unable to spend their time learning a new skill, or who are not able to afford the necessary equipment. For these reasons, indie sewing patterns cannot replace the need for size inclusive ready-to-wear fashion. An ambitious way to extend the benefits of indie sewing pattern access to those who are not able to sew their own clothes would be to form a community organization wherein sewists donate their time and sewing skills to create custom garments for others in exchange for financial compensation or skill trades. An organization like this would benefit the pattern designers, as their products would be purchased by customers who otherwise would not be supporting their businesses. It would also benefit home sewists who want to practice their craft without accumulating more clothing in their personal collections. These suggestions are merely a few ideas that could push this community closer to becoming a truly radical alternative to the existing fashion system.

99 Volanté, Fat Fashion, 174.

100 Wilkinson, Helen & Somos, Caroline, hosts. “Episode 203: Colour, Print, and Patchwork with Samantha of Purple Sewing Cloud,” April 4, 2022, in Love to Sew, producers Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos, podcast, MP3 audio, 01:12:00, https://lovetosewpodcast.com/episodes/episode-203-colour-print-and-patchwork-with-samantha-of-purple-sewing-cloud/.

101 Wilkinson, Helen & Somos, Caroline, hosts. “Episode 203: Colour, Print, and Patchwork with Samantha of Purple Sewing Cloud,” April 4, 2022, in Love to Sew, producers Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos, podcast, MP3 audio, 01:12:00, https://lovetosewpodcast.com/episodes/episode-203-colour-print-and-patchwork-with-samantha-of-purple-sewing-cloud/.

Conclusion

When contemplating the mainstream fashion industry, envisioning true progress towards sustainability, representation, and inclusivity is a bleak endeavor. The ready-to-wear fashion space is hesitant to make visible changes towards meaningful size inclusivity, and the snails-pace progress we have seen in this area has been thoroughly underwhelming. Within the indie sewing space, however, meaningful progress feels much more tangible.

References

Bain, Jessica. “Darn Right I’m a feminist…Sew what?” the Politics of Contemporary Home Dressmaking: Sewing, Slow Fashion and Feminism.” Women’s Studies International Forum 54, (2016): 57-66.

de Castro Peake, Elisalex. “Marie Shirt & Dress”. By Hand London, 2023. https://byhandlondon.com/products/marie-shirt-dress-pdf-sewing-pattern-uk-2-38

Emery, Joy Spanabel. “New Challenges: 1960s–1980s.” In A History of the Paper Pattern Industry: The Home Dressmaking Fashion Revolution, 178–194. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Evans, Calla, Mindy Stricke, Ben Barry, and May Friedman. “Sizing Up Gender: Bringing the Joy of Fat, Gender and Fashion into Focus.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 12, no. 2 (2021): 229-260.

Evans, Calla. “You Aren’t What You Wear: An Exploration into Infinifat Identity Construction and Performance through Fashion.” Fashion Studies 3, no. 1 (2020).

Gurnoe, Chelsea. “Friday Pattern Company.” Friday Pattern Company, 2022. https://fridaypatterncompany.com/.

Kelleher, Leila, and Jess. “Muna and Broad”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.Munaandbroad.com/.

Kelleher, Leila, and Jess. “Additional Sizes: Grading up our Patterns for you”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.Munaandbroad.com/pages/custom-grading-for-larger-sizes.

Kelleher, Leila, and Jess. “About Us”. Muna and Broad, 2022. https://www.Munaandbroad.com/pages/about.

Martindale, Addie & McKinney, Ellen. (2018) “Exploring the inclusion of home sewing pattern development into fashion design curriculums”. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education.

Martindale, Addie. “Home Sewing Transformed: Changes in Sewing Pattern Formats and the Significance of Social Media and Web-Based Platforms in Participation.” In Patternmaking History and Theory, edited by Jennifer Grayer Moore , 149–162. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

Martindale, Addie and Ellen McKinney. “Sew Or Purchase? Home Sewer Consumer Decision Process.” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management 22, no. 2 (2018): 176-188.

Mitchell, Allyson. “Sedentary Lifestyle: Fat Queer Craft.” Fat Studies 7, no. 2 (2018): 147-158.

Moore, Jennifer Grayer. “A Brief History of Patternmaking”, 15. In Patternmaking History and Theory, edited by Jennifer Grayer Moore , 11–30. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

Muenter, Olivia. “Fast Fashion Is Bad for the Environment. For Many Plus-Size Shoppers, It’s the Only Option.” Refinery29, November 20, 2021. https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2021/11/10781654/plus-size-fast-fashion-ethics.

Nielsen, Megan. “Introducing Extended Sizing.” Megan Nielsen Patterns, June 29, 2018. https://blog.megannielsen.com/2018/06/introducing-extended-sizing/.

Peters, Lauren Downing. “Flattering the figure, fitting in: The design discourses of stoutwear, 1915-1930.” Fashion Theory 23, no. 2 (2019).

Peters, Lauren Downing. “You are What You Wear: How Plus-Size Fashion Figures in Fat Identity Formation.” Fashion Theory 18, no. 1 (2014): 45-71.

Russum, Jennifer Ann. “From Sewing Circles to Linky Parties: Women’s Sewing Practices in the Digital Age.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2016.

Rushmore, Jenny. “Cashmerette: Sewing for Curves.” Cashmerette, 2022. https://www.cashmerette.com/.

Rushmore, Jenny. Ahead of the Curve. London. Quadrille by Hardie Grant, 2021.

Sewcialists blog.”Curvy Sewing, One Year Later: Where Are We Now?” Sewcialists, February 21, 2020. https://thesewcialists.com/2020/02/21/curvy-sewing-one-year-later-where-are-we-now/.

Thiel, Stephanie. Rad Patterns, 2022. https://www.radpatterns.com/about-me/.

Thompson, Emma. “Labour of Love: Garment Sewing, Gender, and Domesticity.” Women’s Studies International Forum 90, (2022).

Tullio-Pow, Sandra, Kirsten Schaefer, Ben Barry, Chad Story, and Samantha Abel. “Empowering Women Wearing Plus-Size Clothing through Co-Design.” Clothing Cultures 7, no. 1 (2020;2021;): 101-114.

Volanté, Paolo. Fat Fashion: The Thin Ideal and the Segregation of Plus-Size Bodies.Bloomsbury, 2022.

“The Vogue Business Autumn/Winter 2023 Size Inclusivity Report.” Vogue Business. March 13, 2023.

Wilkinson, Helen. Helen’s Closet Patterns, 2022. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/.

Wilkinson, Helen. “Curvy Sewing Survey Results”. Helen’s Closet Patterns, January 25, 2019. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/.

Wilkinson, Helen. “Curvy Sewing Survey”. Helen’s Closet Patterns, November 27, 2018. https://helensclosetpatterns.com/.

Wilkinson, Helen & Somos, Caroline. “Episode 203: Colour, Print, and Patchwork with Samantha of Purple Sewing Cloud”. Produced by Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos. Love to Sew, April 4, 2022. Podcast, 01:12:00. https://lovetosewpodcast.com/episodes/episode-203-colour-print-and-patchwork-with-samantha- of-purple-sewing-cloud/.

Wilkinson, Helen & Somos, Caroline. “Episode 241: Sew Outdoorsy with Claire Birnie”. Produced by Helen Wilkinson and Caroline Somos. Love to Sew, September 25, 2023. Podcast, 00:59:00. https://lovetosewpodcast.com/episodes/episode-241-sew-outdoorsy-with-claire-birnie/.

Author Bios

Chloe Numbers (she/her) is a graduate of the MA Fashion program at Toronto Metropolitan University. Her major research project focused on embodiment theory and the fashioning of fatness in 1930’s women’s fashion media. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in Film Studies and from the University of British Columbia. Her primary research interest is fashion history, particularly in relation to the fashioning of women’s bodies. Chloe’s additional research interests include fashion and fatness, the history of sewing and other domestic crafts, historical footwear, and fashion history in the Jewish diaspora.

Article Citation

Numbers, Chloe. “A Radical Alternative: Pursuing Size Inclusivity in the Indie Sewing Community.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-29, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050104

Copyright © 2024 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)