Works Cited

“Alien.” Merriam-Webster, 2019, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alien.

Arvin, Mail, et al. “Decolonizing Feminism: Challenging Connections Between Settler Colonialism and Heteropatriarchy.” Feminist Formations, vol. 25, no. 1, 2013, pp. 8-34.

Bailey, Emily Grace. “Alien Beauty.” WGSN, 24 October 2018, https://www-wgsn- com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/content/board_viewer/#/81404/page/1.

Boucher, François. Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour, c. 1750, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour.” Wikimedia Commons, 17 November 2012, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jeanne-Antoinette_Poisson,_Marquise_de_Pompadour,_by_Francois_Boucher,_1750_with_additions_by_c.1750_and_by_1781_-_Fogg_Art_Museum_-_DSC02299.JPG.

---. Madame Bergeret, c.1766, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. “Madame Bergeret.” Google Arts & Culture, artsandculture.google.com/asset/madame-bergeret/TwFs06EqPBEgug.

Botticelli, Sandro. Birth of Venus, c. 1482, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy. “Birth of Venus,” Artstor, artstor.wordpress.com/2016/12/15/artstor-searches-highlight-women/scala_archives_1031314669/.

David, Jacques-Louis. Portrait of Madame de Verninac, c. 1799, Louvre Museum, Paris, France. “Portrait of Madame de Verninac.” Wikimedia Commons, commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_de_madame_de_Verninac_by_David_Louvre_RF1942-16_n2.jpg.

Gainsborough, Thomas. Mary Heberden, c. 1777, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. “Mary Heberden.” Google Arts & Culture, artsandculture.google.com/asset/mary-heberden/LQGnIwkNP3dJBA.

Gomel, Elena. Science Fiction, Alien Encounters, and the Ethics of Posthumanism: Beyond the Golden Rule. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Halpern, Daniel, et al. “‘Selfie-ists’ or ‘narci-selfiers’?: A cross- lagged panel analysis of selfie taking and narcissism.” Personality and Individual Differences, vol. 97, 2016, pp. 98-101.

Haraway, Donna. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. Routledge, 1991.

Hernandez, Gabriela. Classic Beauty: The History of Makeup. Schiffer Publishing, 2017.

Hungry. “The Official Website of Hungry (@isshehungry).” Hungry, https://www.isshehungry.com/bio/.

Ingres, Jean-Auguste-Dominique. Comtesse D’Haussonville, 1845, the Frick Collection, New York, New York. “Comtesse D’Haussonville.” Wikimedia Commons, commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean-Auguste-Dominique_Ingres_-_Comtesse_d%27Haussonville_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg#mw-jump-to-license.

Jowett, Victoria. “There’s a new Jeffree Star eyeshadow palette coming, and the internet can’t cope.” Cosmopolitan, 1 November 2018, www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/makeup/a24506408/jeffree-star-alien-eyeshadow-palette/.

Justice, Christopher. “Sidney I. Dobrin, ed. Writing Posthumanism, Posthuman Writing.”Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, vol. 32, 2017, pp. 1-4.

Kasriel-Alexander, Daphne. “Get Over It! #NoFilter Is Dead and Selfie Editing Empowers You.” Creative Contagious, 1 February 2018, medium.com/creative-contagious/let-selfie-editing-out-of-the-doghouse-whats-wrong-with-an-app-grade-628a5ea369dc.

Lonergan, Alexandra Rhodes, et al. “Me, my selfie, and I: The relationship between editing and posting selfies and body dissatisfaction in men and women.” Body Image, vol. 28, 2019, pp. 39-43.

Lupton, Ellen. Skin: Surface, Substance, and Design. Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.

MacCallum, Fiona, and Heather Widdows. “Altered Images: Understanding the Influence of Unrealistic Images and Beauty Aspirations.” Health Care Analysis, vol. 26, no. 3, 2018, pp. 235-45.

Maddox, Jessica Leigh. “Fear and Selfie-Loathing in America: Identifying the Interstices of Othering, Iconoclasm, and the Selfie.” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 51, no. 1, 2018, pp. 26-49.

Manet, Edouard. Olympia, c. 1863–1865, Musée D’Orsay, Paris, France. “Olympia.” Artstor, artstor.wordpress.com/2016/12/15/artstor-searches-highlight-women/lessing_art_1039490311/.

Mills, Hailey L. “Avatar Creation: The Social Construction of ‘Beauty’ in Second Life.” Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 95, no. 3, 2017, pp. 607-24.

Patzer, Gordon L. The Physical Attractiveness Phenomena. Plenum Press, 1985.

Plewka, Karl. “Subverting Selfie Culture.” Business of Fashion, 28 May 2018, www.businessoffashion.com/articles/beauty/pushing-boundaries-in-the-age-of-virtual-vanity.

Proulx, Mikhel. “Protocol and Performativity: Queer selfies and the coding of online identity.” Performance Research: A Journal of Performing Arts, vol. 21, no. 5, 2016, pp. 114-18.

Solarin, Ayoola. “Juno Birch makes an art out of taking the piss.” Dazed Magazine, 29 June 2018, www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/40526/1/juno-birch-makes-an-art-out-of-taking-the-piss.

Thompson, Gregory. “15 Most Stunning Aliens in Star Trek.” Screen Rant, 20 October 2017, screenrant.com/star-trek-steamiest-aliens/

Tirosh-Samuelson, Hava. “Transhumanism As A Secularist Faith.” Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, vol. 47, no. 4, 2012, pp. 710-34.

Weinstock, Tish. “This make-up artist is redefining beauty with her extreme looks.” i-D, 3 May 2018, i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/a3yxdb/this-make-up-artist-is-redefining-beauty-with-her-extreme-looks.

Whitelocks, Sadie. “Eight hours getting ready for a night out? Powerful self-portrait series reveals male photographer’s elaborate party looks.” DailyMail, 25 November 2013, www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2513315/Ryan-Burkes-self-portrait-series-reveals-photographers-elaborate-party-looks.html.

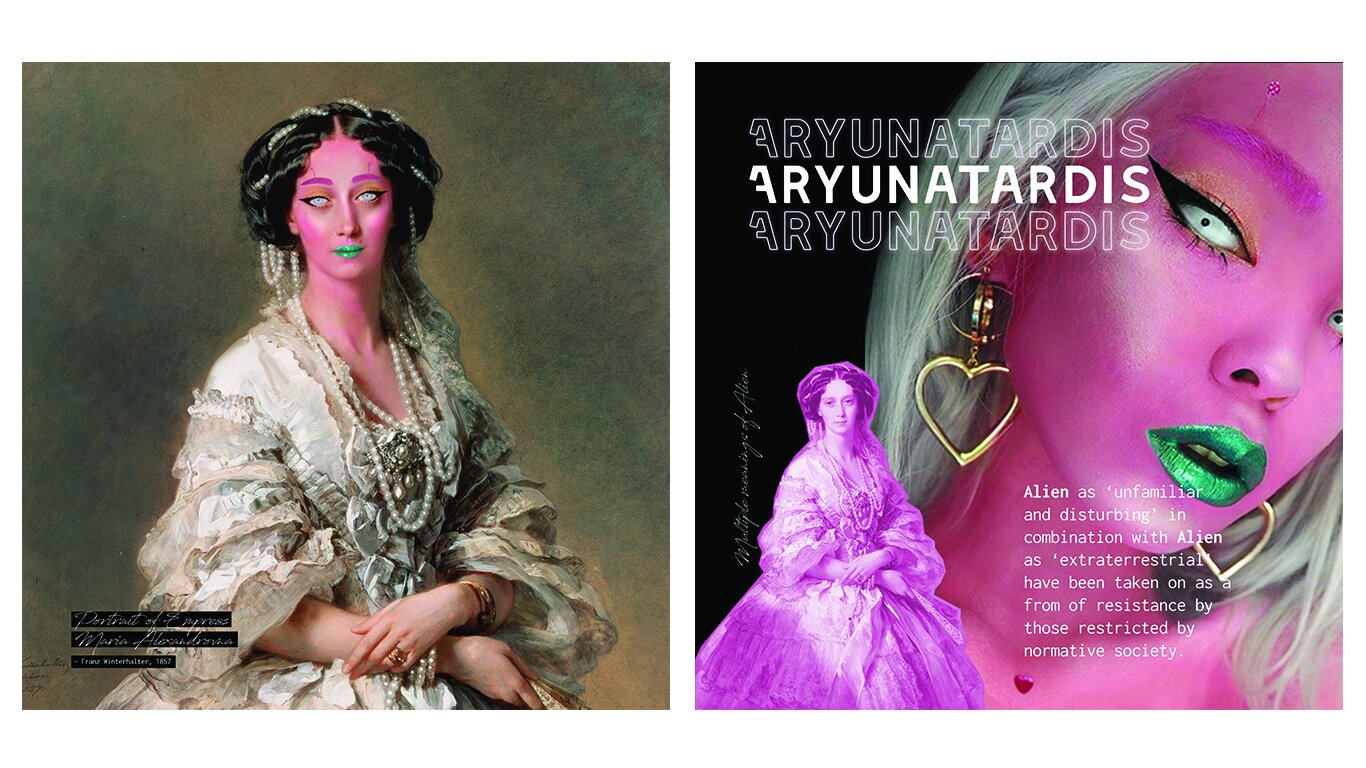

Winterhalter, Franz Xaver. Portrait of Empress Maria Alexandrovna, c. 1857, State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia. “Maria Alexandrovna.” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maria_Alexandrovna_by_Winterhalter_(1857,_Hermitage).jpg.