Boots on the Ground: Footwear, the Body, and Loss

By Laura Levitt

DOI: 10.38055/FCT040102

MLA: Levitt, Laura. “Boots on the Ground: Footwear, the Body, and Loss.” Corpus textile, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040102

APA: Levitt, L. (2025). Boots on the Ground: Footwear, the Body, and Loss. Corpus textile, special issue of Fashion Studies, 4(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040102

Chicago: Levitt, Laura. “Boots on the Ground: Footwear, the Body, and Loss.” Corpus textile, special issue of Fashion Studies 4, no. 1 (2025): 1-20. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040102

Special Issue Volume 4, Issue 1, Article 2

Keywords

Grief

Loss

The body

Holocaust Memory

Auschwitz

Abstract

This essay is about entanglements, trips and tripping. The body speaks when there are no words; the death of a beloved parent and a pilgrimage to Auschwitz and its landscape of destruction. It is about the numbness of loss and how it is embodied. This came together for me in Auschwitz as a palpable discomfort, an undoing that I could not otherwise touch. This is a story I am still piecing together, a narrative whose logic is associative. It takes its title from a phrase bound to battle, troops in combat, storm trooper invading and claiming ground. My battle, an internal struggle, grief and loss as expressed in a rib that broke after my father died, and a pair of boots that fell apart in Auschwitz.

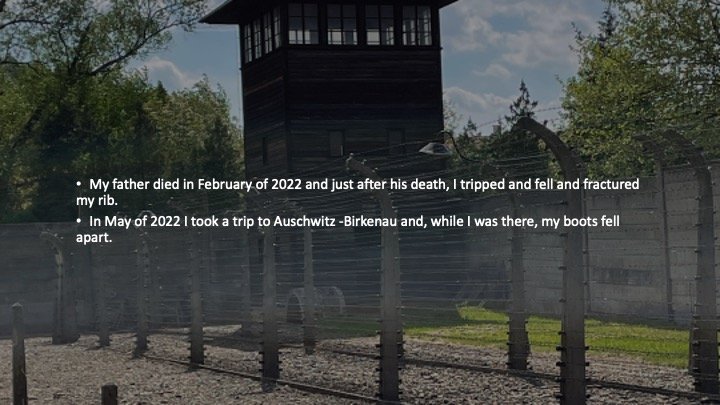

Figure 1

Author's photograph.

Figure 2

My father, some of his books, one of his paintings, Author’s photographs, Portrait of Irving Levitt by Gary A. Knox, 2017.

Figure 3

Shoes, Corsets, and Prosthetics. Author’s photograph.

Boots, shoes, corsets, and clothing are prosthetic devises, extensions of the body.[1]

The body speaks when there are no words.

Grief, loss, and trauma are bound up with each other.

Different losses are often experienced together.

Losses are embodied, bound together in the body.

This essay is about entanglements, trips and tripping. The body speaks when there are no words; the death of a beloved parent and a pilgrimage to Auschwitz and its landscape of destruction. It is about the numbness of loss and how it is embodied. This came together for me in Auschwitz as a palpable discomfort, an undoing that I could not otherwise touch. This is a story I am still piecing together; a narrative whose logic is associative. It takes its title from a phrase bound to battle, troops in combat, storm trooper invading and claiming ground.

Faltering Narratives

This is a nested tale told through the powerful enabling words of others. To write this faltering narrative, I have found myself in the company of Judith Butler and Maggie Nelson. I come to Butler belatedly through Nelson’s reflections on her own struggle to tell the story of “the trial of the man accused of murdering [her] aunt,” a tale that enabled me to write about my rape in The Objects that Remain, and now in a different way about my father’s death and this trip to Auschwitz.

As Nelson explains in her essay “The Call” (2022), she kept Judith Butler’s Precarious Life (2004) “close by her side” as she struggled to find words to write about what it was like to be in that Michigan courtroom in 2005 witnessing not only the testimony but the physical remains, the evidence from her aunt’s 1969 murder almost 40 years later.[2] Seeing that evidence, a pair of pantyhose, a wool jumper, a raincoat, and the autopsy photographs of her aunt’s limp body—recognizing her mother and herself in those remains—was her undoing. Maggie Nelson had just published Jane: A Murder (2005), a book of narrative poems about her aunt’s life and death when, in an uncanny turn of events, there was a break in that very cold case. The story came back to life, and Butler’s words were there with her in that courtroom offering some company.

Nelson would later tell this faltering narrative of the trial in her memoir, The Red Parts (2007). As I tried to write about my rape, I held tight to both of Maggie Nelson’s books, Jane: A Murder and, most especially, The Red Parts. They were my companions as I considered the missing evidence in my case—my sweatpants, the blanket and sheets taken from my bed—items that would never make their way to any courtroom.

And so, as I headed off, in the summer of 2005, to the trial of the man accused of murdering my aunt, I kept Precarious Life close by my side. Its observations about grief and storytelling--'I tell a story about the relations I choose, only to expose, somewhere along the way, the way I am gripped and undone by those very relations. My narrative falters, as it must' (23)--offered me not only insight and comfort, but also formal inspiration as to how one might allow narrative faltering to act as a powerful presence while one is trying to relay a story." (Nelson, “The Call” 59)

For Nelson, “the red parts” not only referred to the viscera of her aunt’s mutilated body, but also to the blood of Jesus, his body on the cross and its transubstantiation; she references the 19th century Red-Letter Bibles in which the words of Jesus were printed in red, as if soaked in his very blood.[3] The interplay between violations that cannot be redeemed and the hope against hope that there will be life after death is something I learned about from Nelson; something she both points to and resists in The Red Parts. What I could not have anticipated after the publication of my own book was how this more recent essay by Nelson could both bring me back to those red parts while also helping me relay this story about losing my father and going to Auschwitz.

I read “The Call” (2022) just before I left for Poland. At that time, I did not yet make these connections. Almost a year later while teaching Nelson’s essay in my graduate research seminar I began to recognize these connections. I had my students read a few of the essays from the special issue of Representations, “Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler” (2022), alongside the Butler texts cited by the contributors. Nelson’s was one of the essays I assigned. In preparation for the class, I decided to read Butler’s “Violence, Mourning, Politics” from Precarious Life first before rereading Nelson.

Reading Butler’s essay, I was struck by a strange sense of familiarity. It was as if I already knew these arguments intimately. So taken by a few key moments in the text, I wrote about them at length. I did this before rereading Nelson’s essay. Once inside Butler’s text, I began to appreciate its proximity to Nelson’s writing. The passages I had singled out were the very ones Nelson had cited: “I tell a story about the relations I choose, only to expose, somewhere along the way, the way I am gripped and undone by those very relations. My narrative falters, as it must” (Butler 23, qtd. in Nelson 59). Finding Nelson writing about her aunt’s murder trial in this new piece, I was startled. I had not taken in this reference when I first read “The Call.” It was only later that I appreciated this connection. Because Nelson had had Butler with her then, I had Butler and Nelson with me in the wake of my father’s death and this trip to Auschwitz. As I groped for inspiration as to how to convey this faltering doubled narrative of violence and mourning, I now had both of these writers with me. And with their help, this essay is a kind of enactment that aspires to reveal some of what a faltering narrative can convey.

These experiences of loss and grief are dreamlike and the close proximity in time between the events of my father's death and this belated visit to Auschwitz, mean that I cannot easily disentangle them—and maybe I should have already appreciated this. After all, I had already written a book, American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust (2007), about my father and the Shoah. But at that time, he was still alive. This was a new reckoning.

[1] For more on this connection between embodiment and clothing, especially shoes, see Ellen Sampson, Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear. For a haunting reading of the empty shoes in the context of the Holocaust, see Ellen Carol Jones’ “Empty Shoes”, a meditation on the figure of these shoes in art and poetry of the Holocaust and beyond.

[2] Given the allure of this text and its power over me, I mistakenly called the text “The Calling” and not “The Call.” I thank Laura Pycock-Kassar and Anne Létourneau for finding this mistake and appreciating how it speaks to the argument I am making.

[3] For more on these issues, the various implications of “the Red Parts” see Laura Levitt, The Objects that Remain, chapter 2, 29-38.

In the camp it was not just that one of my travel companions was there with a family story; a story of a grandfather close to my father's age who was there as a political prisoner and survived, or the fact that my father was a WWII veteran, or that his parents came to the United States just as the gates to immigration were closing in the early 1920s, that they had more distant relatives still in Eastern and Central Europe during the Holocaust, or the fact that my father grew up in a Yiddish-speaking home but never spoke the language himself, instead learning German in school.

What I tried to show in that book was how different losses, even incommensurate experiences of grief, can and do inform each other. The iconic landscape of Auschwitz was a part of my father's visual repertoire—all that barbed wire, all those watchtowers, the dark foreboding gloom of so many black and white images in books all around our home as I was growing up but also as repeated figures in my father’s own drawings and paintings despite that fact that he had never been there.

There is a small watercolor painting I have in my office at Temple that depicts just these things. The painting includes no faces, my father’s usually ubiquitous signature as an artist. Instead, it simply shows a snippet of this dark landscape. The mood is ominous. The watercolors are in shades of black, deep olive green and brown. Returning to this small painting, I note a streak of red on the horizon.

My father’s painting feels connected to this photograph I took in Auschwitz (see Figure 5), my attempt to place myself in this strangely familiar place. The ubiquitous barbed wire fencing and those watch towers are in so many of my photographs from that day. I think it was their familiarity that made me take all those pictures.

Figure 4

My Father’s Painting. Author’s photograph, Irving Levitt watercolor, undated, circa 1990.

Figure 5

The author at Auschwitz, Author’s Photograph.

This photograph stands out among the many I took that day; a partial rendering. You can see only a portion of my face but what is clear is the backdrop. Behind and beside me is Auschwitz, a small sliver. But unlike the Auschwitz of my imagination, the watchtower is captured in the light of day. And yet, despite the brightness of the sky, my eyes are down cast, at least the eye in view appears this way. My brow is furrowed. The lines on my face are pronounced, the grey in my eyebrow and my now curly hair are quite evident. This is a late shot.

My father never imagined this place in the warm light of spring as I was seeing it. Yet, here I am. I am in this place and not another.

I promised to talk about boots on the ground.

My Boots

The relationship between the self and the garment, simultaneously bodily and not of the body, may be encapsulated in the verb “to cleave.” To cleave… means both to join together and to spilt apart. We may refer to things cleaving together and also cleaving apart (Sampson 119).

Before I went to sleep one night while writing a version of the talk that would become the basis for this essay, what insinuated itself into my internal recitation of this narrative was the memory of an 8mm film my father made in the 1950s, a film I had written about in American Jewish Loss. I started thinking about “the feet”—my boots, my feet and the film’s title, The Thud of His Defeat—an homage to a poem by Stephen Crane about the fragility of justice, and also about death, a strangely Christian poem.[4] But it was not so much the poem or the film's narrative that came back to me, rather, it was a small moment in the reel—the director's, my father’s, signature.

In this silent 8mm production, there is a scene when the protagonists, desperate and poor, clothes in tatters, stumble through the streets of Albany, NY and cross paths with a dapperly dressed gentleman. Just after offering them some money, this debonair character, about to cross the street, trips at the curb, loses his footing and stumbles. This is my father, his projection on the screen in what is otherwise a film he worked on behind the scenes as writer, producer and director. This stumble was not scripted but remains a part of the final cut. The scene depicts “the thud of his the/de feet" as a performance studies scholar once suggested to me as I presented these frames at NYU many years ago.[5] What are these connections—feet, tripping, taking a trip, boots and shoes, but also the fear of falling, an actual fall, and the return to my own fears about falling as my boots came apart in Auschwitz?[6] Slowly, these musings brought me back to this halting narrative about my father’s death and Auschwitz.

I bought this pair of boots at a small consignment shop that I had, at the time, only recently discovered, three years before my trip.[7] These were practical boots and once I learned that the weather in Auschwitz would be rainy, I decided to take them with me.

I wore the boots on the flight to Poland. In retrospect, I remember noticing that the lip at the front of one of them seemed a little loose, but nothing to worry about. The boots seemed fine. I now suspect that this small clue may have been the beginning of their coming undone; although I am not sure how to explain both boots coming apart.

Figure 6

My boots. Author’s Photograph.

[4] See Laura Levitt American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust for more about the film and the poem. See especially chapter 3, 85-146. The Christian resonances also resonate with Nelson’s engagement with the words of Jesus written in red.

[5] Laura Levitt, “Telling Stories Otherwise (or Revisiting My Father’s Visual Archive)”.

[6] I thank one of my anonymous reviewers for helping me appreciate that one of the associative strands of my argument throughout this essay has to do with homophony, of words that sound alike but hold different meanings. Here these are not simply a coincidence, although I have always found coincidences meaningful but following Lacan, in these connections, the unconscious speaks. For more on this see, Russell Grigg, “On Linguistry and Homophony,” PyschoanalysisLacan Volume Three Papers, Lacan circle of Australia, https://lacancircle.com.au/psychoanalysislacan-journal/psychoanalysislacan-volume-3/on-linguistry-and-homophony/.

[7] The shop did not have a huge amount of merchandise but there were some lovely higher-end items and some nice shoes. The boots were on sale, and so I bought them. They are a simple black leather pair with a small heel and zippers that make it easy to take them on and off. They carry a Stuart Weitzman label. They were a good addition to my boot collection. Other pairs I had were either over the knee or short booties, more shoes than boots.

My Trip to Auschwitz

My father died in early February of 2022. His death was difficult and confusing. I had worried a great deal about his fragile health and had assumed that he might be in hospice care by spring, but no one on his care team thought he would be dying anytime soon. He had just seen the lung specialist and they were working on a treatment for the fluid that had built up in and around his lungs, a side effect of Parkinson’s, the inability to swallow food properly. Although it’s an ultimately incurable condition, they were confident that the procedure would be effective. He was scheduled for an X-ray; between the minutes when the X-ray technician stepped out and returned, my father was gone. The physician on duty called me; I heard in his voice how startled he was by my father’s sudden death. I was just beginning to take in the news of his prognosis and treatment. We thought we still had time.

Shocked by his sudden death, I could hardly feel anything, then I tripped. Within two days of my father's death, I stumbled, tripped, and fell while walking my dog, and it hurt. It hurt so much that I called my doctor who insisted that I go to the hospital for a series of chest X-rays. She wanted to be sure that I had not broken a rib. I had the X-rays my father was supposed to have had, and they showed that I had indeed fractured a rib on my right side. The pain was sharp and persistent it was my way out of the numbness, out of any rehearsed but unfelt grief. It was my body's way of expressing my pain. It seems I could not get there any other way.

Yet, his death made space for this trip. I headed to Poland in early May.

I had been to only one other concentration camp before going to Auschwitz. I went to Sachsenhausen outside of Berlin with my partner. That was about five years ago. We took a train from Berlin and then walked to the camp from the station. We did this on what turned out to be an extremely sunny and warm summer's day. It was too hot, too dusty, and too sunny to be at a concentration camp.[8]

The whole experience made me extremely anxious. I obsessed over the train schedule. The trip was delayed; our train arrived late at the station. It was an inauspicious beginning. The walk was long and incongruous. We made our way through the lovely small town and into a residential area adjacent to the camp. The houses in this neighborhood all had beautiful gleaming tile roofs and lovely flower gardens. As we got closer to the camp, there was a police training facility. It was right next to the entrance to the camp complex. We did not have a guide. We put on the headsets and took the tour on our own. For the first half-hour or so of being there I could not get my headset to work. I kept listening to the first few descriptions over and over again until I finally got the tape to work. It was irritating. We spent some time in the cemetery near the opening gate into the camp proper and also looked in briefly at the museum across from the cemetery. This camp had been in the former East Germany and its Soviet and communist history were everywhere apparent, including in the stained-glass window in the entryway to the museum. That liturgical window depicted a red soldier as savior at its center, standing in his red cape where one might have expected to find an imagine of Jesus. This heroic account of the Soviet army as liberators and saviors became even more prominent in the grand workers' monument inside the campgrounds.

Much of what was once the camp is no longer standing. Some barracks were reconstructed; a few other buildings remain standing including the kitchen and the medical facility. There was an ugly and frightening exhibit in the medical barrack that included a detailed account of the medical crimes committed in this place.[9]

It was very hot and there was no shade in the heart of the camp which made walking around more difficult especially with my partner who has to be extremely careful in the sun. What I remember feeling most while I was there was confusion and frustration. I felt guilty about not getting to everything and exhausted by all that there was to see. In one of the reconstructed Jewish barracks, I felt I had to open each and every drawer out of respect for all who had perished in this horrible place, but I got tired. We never made our way through the museum. I did walk up inside one of the guard towers and was again aghast at how close those idyllic houses, with their lovely shiny roofs and pretty gardens, were to this camp. The ramp to the gas chamber was so very close to those homes; right next door, it seemed to me.

Figure 7

En route to Auschwitz. Author’s Photograph.

[8] Somehow it was never supposed to be sunny in a concentration camp. This was outside of my imagination that such places could be bright, and light-filled.

[9] For more on the chilling exhibition in the medical barrack, see “Medical Care and Crime. The Infirmary of the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp 1936-1945,” https://www.sachsenhausen-sbg.de/en/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/medical-care-and-crime/.

I kept wanting there to be a right way to honour what happened in this place. I wanted something solid to hold onto, a correct procedure, and I didn't have it; we didn't have it. I left feeling nauseous and irritated. I did not want to come back and spend more time. I wanted out. But Auschwitz was the camp of camps and as a scholar of Holocaust memory, I felt compelled to go there at least once in my life, and this time, I was prepared. My friend hired an excellent guide, and we spent the day with him making our way through both Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau.[10]

I felt like I was walking on pieces of rock that were stuck to the bottom of my shoes. The grounds at both Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau are, in fact, covered with gravel. When I initially began to feel this discomfort early on at Auschwitz I, I turned over the foot in question and checked the sole of my boot to be sure that there weren't stones stuck to the bottom, like what happens when you step on a piece of chewing gum and other things begin to accumulate. There was nothing there but still I kept feeling those stones. They became an abiding irritant, a part of my experience at Auschwitz.

It was only as we stopped at the cafeteria for a bowl of soup before leaving Auschwitz I that I was able to examine my boot more carefully. I slowly realized that gravel had wedged into the welt, the leather rim sewn around the edge of the boot’s upper to which the sole is attached. Using my hands, I worked the rocks out and hoped that, more conscious of the problem, I could avoid this happening again as we made our way through Birkenau. Despite my optimism, the situation worsened. By the time we worked our way back from the Sauna Building at the far end of the camp, both of my boots began to flap. The gravel had unhinged both soles. It would have been funny, clownlike, had it not been so dangerous. I was increasingly worried about tripping as we made our way back to the car.

At the end of the day, I was grateful that I had brought a pair of sneakers with me. What I cannot explain is why I did not change into those sneakers on the way to Birkenau.

For this essay, I asked my friend in Poland to send me her pictures. I was hoping to see my boots on the ground. When her images arrived, I was struck by the fact that I had not remembered what I was wearing. There is something strange about seeing unfamiliar images of oneself but especially in this place.

There were not many pictures of me outside that show my full body and boots on the ground among those she sent. The only one I have is this one taken at the entryway into the remaining crematorium at Auschwitz I. We were near the gate that leads to the house of the Kommandant where his children once played.[12] This proximity has always upset me having read about it and seen it depicted on film but being there and seeing it for myself was even more devastating, especially on a bright sunny day.

These jarring juxtapositions are part of why the beautiful light, the warm weather, and the lilacs in bloom at Auschwitz I were so upsetting. This place should be in black and white, or at least in dark and somber colors like my father's paintings. But it is not. In the photograph (see Figure 8), I am with my colleague Matt. I am holding my lower back. I don't know if my back hurt, but the gesture feels familiar. You can see our backs as we are about to enter this underground space.

[10] The Auschwitz complex is made up of two main camps 2.5 kilometers apart from one another. The original, Auschwitz I created in an abandoned series of Polish army barracks is just outside the city of Oswiecim. The camp began in April of 1940. The killing center of Birkenau or Auschwitz II-Birkenau is located just over three kilometers from the original camp and construction began in 1941. For more on the camps and the even larger camp complex of many subcamps, see the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s online publication, The Holocaust Encyclopedia, “Auschwitz,” accessed October 16, 2023.

[11] See “Welt,” Oxford Language Dictionary, accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.google.com/search?q=Welt&rlz=1C5CHFA_

[12] Jonathan Glazer’s award-winning 2023 film, “The Zone of Interest” was released after I wrote this essay. It is a meditation on the quotidian horrors of Auschwitz and its Kommandant, Rudolf Höss, and his family living in such close proximity to the death camp; literally within what the Nazis call “the zone of interest” and as I explain, the Höss family lived just steps away from the camp.

Figure 8

Laura and Matt walking outside. Author’s photograph, by Karolina Krasuska

Figure 9

Wall of Pictures in the Sauna Building. Author’s photograph, by Karolina Krasuska.

This is a photograph taken in the former Sauna Building, the last place we stopped on our tour. It is a bit off the beaten track, but of course the track, even out there, was covered in rubble, those same insinuating rocks and my boots were already in pretty bad shape. In this picture, I think I can see the accumulation of dust all over them.

I am standing in front of a vast wall of family photographs. These are images from the last Polish transport to Auschwitz that I wrote about at length in American Jewish Loss. It felt right for me to be there with them. Before this trip, I had a hard time imagining what a Sauna Building might actually look like and how the images would be displayed.

Figure 10

The Names. Author’s photograph, by Karolina Krasuska.

The photograph my friend finds most compelling was taken at Auschwitz I. Here, the names of all those who perished are documented. Like a huge over-sized collection of phone books all arranged in alphabetical order, the names go on and on.[13] The pages are vast. They remind me of a perverse version of Helène Aylon's The Book that Will Not Close.[14] In the picture, I am standing with our guide at the far end of the display. The photograph shows the compendium on the left, a long display of manila pages, but the size and vastness of the exhibit is confusing. Is this some kind of sculpture tangibly signifying the magnitude of the horror? What about all those names? My body at the far end of the room makes clear the scale of this memorial.

In “The Call,” Maggie Nelson writes about becoming undone as a political act. Like Judith Butler, she draws connections between intimate injury and loss, her mentor and my friend Christina Crosby’s broken neck and paralysis, and grand political and social disasters, 9/11 and patriarchy. My grief is both about my father and about Auschwitz. Nelson writes:

Figure 11

Maggie Nelson Quote from “The Call”, Author’s photograph.

[13] These are the names of Jewish victims specifically, and it is famously noted that many victims were not included due to lack of information. This compendium spans all camps/ghettos/etc., not just Auschwitz. Book of Names was a project by Yad Vashem. It is continuously updated as new information surfaces (latest 2023). “The Book of Names- New at Yad Vashem”, https://www.yadvashem.org/museum/book-ofnames.html#:~:text=Yad%20Vashem's%20Book%20of%20Names,with%20memorial%20sites%20and%20more%20%E2%80%93. For more information about the version of this memorial in Auschwitz I, see “Shoah, Block 27,” https://www.auschwitz.org/en/visiting/national-exhibitions/shoah-block-27/.

[14] This piece was part of Aylon’s “The Liberation of G-d” project. For more on Aylon’s life and her work, Helène Aylon, Whatever is Contained Must Be Released: My Orthodox Jewish Girlhood, My Life as a Jewish Feminist Artist.

This last piece from Nelson’s essay brings me back to my experience at Auschwitz. My numbness comes, at least in part, from all of the expectations that I brought with me, all of the lessons and understandings of this place that already shaped what I was supposed to enact—to do, to feel. I think I wanted to be open to what it was that I felt and perhaps the lack of sensation in that encounter that was only slowly growing in intensity as my feet began to hurt and my boots began to fall apart. This was my way in.

As Sampson explains, these vestiges of once vibrant lives can’t help but remind us of those who once wore them. All those lost pairs of shoes continue to cleave to those now long-absent bodies. The open bins of shoes on display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC—shoes that regularly make their way back and forth between Poland and the United States—bring visitors there into proximity to this horrific place and that time.[15] Perhaps having finally seen all of these shoes on permanent display at Auschwitz I, my own boots could not bear the weight of this reckoning.[16]

What is the legacy of Auschwitz, of the Holocaust? Is it really already known? I don’t think so. I think we need to let it undo us, to feel this for ourselves. Without doing so, we simply reiterate a familiar litany. We don't allow ourselves to feel our own vulnerability. We don’t take in what Auschwitz means for us now in the present. And perhaps, more importantly, what we take with us as we leave this place. What I am trying to get at is the slow process of undoing, of unravelling even what we thought we knew. This is part of what it means to perhaps commemorate the Holocaust in the present noticing the small things that are our own experiences of being in Auschwitz. Perhaps this is, in part, what we need to say and do now in order not to be complacent with the litany, the ones we already know. Part of what I take away from my trip to Auschwitz is the way that even knowing about “the Holocaust” or writing about it at this distance of time and geography does not stop us from being undone in the present, but only if we pay attention to what might appear to be the small things, a pair of boots whose undoing offer a clue to what it means to submit to a transformation, “the full results of which cannot be known in advance” (Butler 21, qtd. In Nelson, 60).

My undoing at Auschwitz was slow. It began small—an irritation—and then grew larger and larger so that by the time I was leaving Birkenau, at the end of our long day's visit, I could hardly walk in my own boots. I felt my precarity keenly. I was afraid of tripping and falling. I had to carefully navigate my way back to the car.

The dismantling of unjust systems is a long, slow process. We experience it through accretion. Although accretion suggests a building up, in this case, it is an unbuilding, layer by layer. Undoing is not about easy slogans like the Holocaust-inspired slogan against genocide, “never again”; it takes time, and it demands that we not try to fix it or to tidy it up. Witnessing this history in this place is a form of grieving. We need to feel our vulnerability in the face of the profound injury that haunts this place. My boots brought me to this understanding. They forced me to confront my own vulnerability. After we left the camp, I wrapped up my broken boots and carried them home where I had them repaired. And when I wear them now, I remember.

Boots, shoes, corsets, and clothing are prosthetic devises, extensions of the body.

The body speaks when there are no words.

Grief, loss, and trauma are bound up with each other.

Different losses are often experienced together.

Losses are embodied, bound together in the body.

[15] On the movement of the shoes between Poland and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC and as part of the permanent exhibit in Washington, DC, see The Objects that Remain, 104-112.

[16] For more on the power and display of shoes as a form of Holocaust commemoration and memory, see Jeffrey Feldman, "The Holocaust Shoe: Untying Memory: Shoes as Holocaust Memorial Experience" and Ellen Carol Jones, “Empty Shoes”.

Works Cited

“Auschwitz”. The Holocaust Encyclopedia, n.d. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/auschwitz.

Aylon, Helène. Whatever is Contained Must Be Released: My Orthodox Jewish Girlhood, My Life as a Jewish Feminist Artist. 2012, The Feminist Press at SUNY.

“The Book of Names-New at Yad Vashem,” https://www.yadvashem.org/museum/book-of-names.html#:~:text=Yad%20Vashem's%20Book%20of%20Names,with%20memorial%20sites%20and%20more%20%E2%80%93.

Butler, Judith. “Violence, Mourning, Politics.” Precarious Life: The Power of Mourning and Violence, 2004, 19-49. Verso.

Feldman, Jeffrey. "The Holocaust Shoe: Untying Memory: Shoes as Holocaust Memorial Experience." Jews and Shoes (Edna Nahshon, Ed.), 2008, 119-130. Berg Publishers.

Gedenkstätte und Museum Sachsenhausen. "Medical Care and Crime. The Infirmary of the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp 1936-1945. https://www.sachsenhausen-sbg.de/en/exhibitions/permanent-exhibitions/medical-care-and-crime/

Glazer, Jonathan, director. Zone of Interest. A24, Extreme Emotions, Film4Productions, House Productions, 2023. 1:45.

Grigg, Russell, “On Linguistry and Homophony”. PyschoanalysisLacan Volume Three Papers, n.d. Lacan Circle of Australia.

Jones, Ellen Carol. “Empty Shoes” Footnotes: On Shoes (Sherrie Benstock and Suzanne Ferriss, Eds.), 2001, 197-232. Rutgers University Press.

Levitt, Laura. American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust. 2007, NYU Press.

Levitt, Laura. The Objects that Remain. 2020, Penn State University Press.

Levitt, Laura. “Telling Stories Otherwise (or Revisiting My Father’s Visual Archive).” [Distinguished Lecture]. The Center for Religion and Media, March 2006, New York University.

Nelson, Maggie. “The Call.” Proximities: Reading with Judith Butler, special issue of Representations, vol. 158, 2022, 57-63.

Nelson, Maggie. Jane: A Murder. 2005 [reissued 2016], Soft Skull Press.

Nelson, Maggie, The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial. 2016, Greywolf Press.

Nelson, Maggie. The Red Parts: A Memoir. 2007, Free Press.

Sampson, Ellen. Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear. 2020, Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

“Shoah, Block 27,” accessed February 6, 2025. https://www.auschwitz.org/en/visiting/national-exhibitions/shoah-block-27/.

“Welt.” Oxford Language Dictionary, n.d. https://www.google.com/search?q=Welt&rlz=1C5CHFA_

Author Bio

Laura Levitt is Professor of Religion, Jewish Studies, and Gender at Temple University. She is the author of The Objects that Remain (2020); American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust (2007); and Jews and Feminism: The Ambivalent Search for Home (1997) and a co-editor of Impossible Images: Contemporary Art After the Holocaust (2003) and Judaism Since Gender (1997). She is currently writing about the offering left at The Tree of Life Synagogue and at George Floyd Square while working on a book about the former East German writer Christa Wolf. https://lauralevitt.org/

Article Citation

Levitt, Laura. “Boots on the Ground: Footwear, the Body, and Loss.” Corpus textile, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040102

Copyright © 2025 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)