Clothing Norms in Nigerian Universities: Negotiating Fashion Towards Social Hegemony

By Adaku Agnes Ubelejit-Nte

DOI: 10.38055/FS050109

MLA: Adaku, Agnes Ubelejit-Nte. “Clothing Norms in Nigerian Universities: Negotiating Fashion Towards Social Hegemony.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-26, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050109

APA: Adaku, Agnes Ubelejit-Nte (2024). Clothing Norms in Nigerian Universities: Negotiating Fashion Towards Social Hegemony. Fashion Studies 5(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050109

Chicago: Adaku, Agnes Ubelejit-Nte. “Clothing Norms in Nigerian Universities: Negotiating Fashion Towards Social Hegemony.” Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2024): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050109

Volume 5, Issue 1, Article 9

Keywords

Clothing Norms

Social body

Social hegemony

Fashion

Visual markers

abstract

Public discourse and scholarship espouse the subjective influence of clothing norms over the natural body as visual markers of the social boundaries of fashion. As a backlash to student fashion on campus with growing incidences of immodest dressing, most tertiary institutions, particularly in Nigeria, introduced dress standards. Scholars have elaborated on how fashion has been used to negotiate social boundaries of power, identity, status, gender, etc. However, these scholars differed on the approval/acceptability and disapproval/unacceptability of the institutional control over clothing behaviour of adults. This article underscores the role fashion plays as an effective driver of social control and hegemony by underpinning sartorial practices in conformity to established institutional expectations and standards of appropriate nuances of formal dressing in institutions of higher learning. From an ethnographic standpoint, the study analyzed the institutional standards of formal dressing or dress codes of different tertiary institutions in Nigeria as posted on their websites in addition to the participant method. This information is equally published in the students' handbooks of these institutions. The post-structural Foucaultian approach to “Discipline and Punishment” is applied as an analytical framework. This approach explains disciplinary power as a mechanism of social control of the body in contemporary society through conformity to approved dress standards in a formal environment like the university. Overall, it is argued that Foucault’s framework provides an understanding of the significance of social control that may be hampered by misconceptions about what other people think of clothing norms.

Introduction

All human organizations (both public and private) are guided by rules that prescribe expected and inappropriate behaviour at any given time and place. These rules are referred to as norms which may either be considered important (mores) with violations that are severely punished or insignificant (folkway) with less severe punishments. The norms considered important are moral obligations usually backed by conventions or laws. Norms vary from place to place and are therefore culturally relative. Clothing/dress norms are institutional rules that regulate dressing behaviour and appearance through the specification of appropriate and inappropriate body supplements and modifications in tertiary institutions.

In response to growing incidences of immodest dressing among students on campus, most tertiary institutions, particularly in Nigeria, introduced clothing standards (Fayokun, Adedeji and Oyebade, 2009). Johnson, Lennon and Rudd (2014) affirm that dress and physical appearance play a critical role in shaping peoples' impressions of others. People are judged based on the way they dress because sartorial practices shape, influence and portray one's self-identity, personality, preferences, tastes, and styles (Lurie, 1981; Tseelon, 1989; Entwistle, 2015). Wearing stylishly torn jeans trousers (crazy jeans), sagging dirty inner wears, or attending lectures in pyjamas with a pair of bathroom slippers may elicit strong social disapproval. In addition to conveying one's affiliation or orientation, the messages communicated by dress are both complex and paradoxical. Dress is characterized by ambivalence as it both liberates and controls the body (Calefato, 2004). Clothes express people’s distinctive social and personal traits.

Regulation of physical appearance and the way bodies are dressed was not unique to the early beginnings of fashion. Dress and body grooming serves as reference points for analyzing the abstract process of social control (Arthur, 1997). Religious groups such as Muslims, Hindus, Judaists, and some Christian groups perceive clothing as symbolic for visible collective identity, maintenance of hierarchical relations, control of sexuality, and the facilitation of conformity to group ideologies (Hume, 2013). Clothing has formed a formidable strategy in navigating ethno-religious boundaries among the Hutterites, Mennonite, and Hasidic Jews. As an important constituent of social control, dress codes are enforced by religious groups to openly symbolize morality and secretly restrain sexuality (Arthur, 2000).

Black and Findlay (2016) acknowledge the growing academic attention to dress standards since Entwistle's (2001) assertion that clothing is “a situated bodily practice.” Glickman (2016), Rabi (2010), Arns (2017), and Meadmore and Symes (1997) problematize the social constructions of the school as a gendered institution and clothing standards for the maintenance of socially constructed gender roles for males and females. Arns (2017) highlights the intersectionality of gender, race, and class in relation to the subjective influence of restrictive dress codes in American high schools, particularly on female Black students. The role of clothing as a medium of internalization and reinforcement of symbolic values and social control is embodied by restricted dress codes such as school, military, or religious uniforms (Crane and Bovone, 2006).

Friedrich and Shanks (2021) investigated the broad shifts in the modes of power through documented uniform policies in Scottish state secondary schools, from disciplinary techniques to shaping students' human capital. The study focused on the complex workings of power through compulsory uniform and dress codes as body techniques used to groom students into disciplinary fashion and as future members of the respectable workforce. The authors analyzed the contents of these uniform policies using the Foucauldian approach to power without examining their applicability in the institutions. Dress codes indicating appearance standards vary according to institution, particularly in service-oriented organizations (Nath, Bach and Lockwood, 2016). Jenkins’ (2014) study adopted the Bourdieusian framework to explain why hospital staff conformed to clothing norms in an institution with few formal dress guidelines. The code of conduct in the Nigerian banking industry stipulates that individuals and corporate members of the industry shall dress in accordance with the dress code of their institution without provoking the other sex (Chartered Institute of Bankers, 2014).

Currently, there is an explosion of research on gender-restrictive dress codes in higher institutions of learning within and outside Nigeria (Dairo, 2023; Pogoson, 2013). Dairo (2023) asserted that dress codes in Nigerian universities were “initially a female problem.”

Some disciplines, especially law, hospitality management, nursing, medicine, and others, require their students to dress more corporately than others. Dress codes have become a common feature of many tertiary institutions, particularly public and privately owned faith-based universities in Nigeria. However, the perceived display and persistence of indecent dressing, especially among female students, and the growing but worrisome issue of sexual harassment by lecturers have led to the institution of dress codes on Nigerian university campuses (Fayokun, Adedeji and Oyebade, 2009; Pogoson, 2013). Existing studies on students’ dress codes have focused on the morality of appearance standards in line with values of decent dressing.

In the present study, dress is viewed as a visible element of fashion, with social control being one of the major themes in the social process of fashion. This study diverges from the previous line of inquiry by examining the notion of fashion as dress and adornment practices that serve as sites for institutional control over the clothing behaviour of adults from a sociological perspective. The purpose of the study is to make evident the role that fashion plays as an effective driver of social control and hegemony by underpinning sartorial practices in conformity with established institutional expectations and standards for appropriate nuances of formal dressing in institutions of higher learning. Specifically, the research examines the following areas: institutional characteristics and their dress and appearance standards; the construction of modest and decent dressing; and the institutional interactions that encourage dress conformity. It also examines how institutional surveillance and threat of consequence influence self-discipline among students. The study analyzes the prohibition of “oppositional dress” in institutions of learning by the establishment of clothing norms or standards through the lens of Michael Foucault's discipline and punishment approach. The justification for this study is based on the institution of dress codes in most Nigerian universities as a response to students’ indecent dressing on campuses.

In this paper, clothing is used as a generic term for dress, grooming, and personal adornments. These terms are used interchangeably to signify what individuals wear, adorn, or modify on the body in everyday life. This includes garments, cosmetics, and accessories for hand, feet, head, nose, ears, neck, mouth, eyes, face, hair, and other objects worn on the body. Both terms refer to objects or body practices for protection, modesty, identity, and aesthetic function. Similarly, norms and codes are used to refer to a system of rules or principles that guide human behaviour.

The Nigerian University System

Livsey (2017) provides the socio-cultural context that led to the emergence of universities in Nigeria. In an effort to meet the higher education needs of Nigerians and to fit into the emergent colonial administrative space, the Elliot and Ashby commissions of 1943 and 1959 were set up. This heralded the establishment of the University College, Ibadan, in 1948 in the south-western region of the country. However, the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, was formally opened in October 1960, as the “first full-fledged, indigenous and autonomous” Nigerian university (unn.edu.ng). Subsequently, five other public universities established within the first decade of Nigeria’s independence were labeled as “first generation” universities. The second generation of public universities emerged between 1970 to 1977, with the addition of state-owned public universities since 1980. Private universities were licensed and established in 1999 to manage the growing demand for university enrolment (Inrougbe, Imhonopi and Eghavreba, 2015), occasioned by the disruptions in the academic calendar as a result of incessant strike actions in the public university system.

There are a total of 106 public and 111 private universities in Nigeria (NUC, 2022) under the supervision of the National Universities Commission (NUC) with the mandate of controlling their intellectual and academic affairs. Livsey (2017) noted the over-bearing impressions made by British lecturers at the University College Ibadan on their students, who were predominantly males at that time. No mention was made about dress codes within this period; rather, a covert socio-political struggle ensued over the preservation of Nigeria’s unique cultural landscape, characterized by quinceanera and the adoption of western dress culture.

Foucaultian Post-structural Approach to Discipline and Punishment

Foucault’s focus was on the penal system, where he advocated a change of strategy from torture (physical power) to conformity to rules (social power) as a means of ensuring prisoner's obedience without harm. Foucault adopted Jeremy Bentham's concept of the “panopticon” as a model for understanding how institutions’ principles of order and control function. He isolates three instruments of social disciplinary power, which include surveillance or hierarchical observation, making normalizing judgments about students' clothing behaviour and punishing deviants. He uses the terms “discipline and punishment” as effective and diffuse mechanisms of social control of the body in contemporary society. This view of disciplinary power as a social technology adapted from the military extends from the penal system to the entire social system (Ritzer, 2008). Similar to prisons, military barracks, and schools, disciplinary power performs a veritable role in contemporary social control of human behaviour. Foucault viewed discipline as a form of power and situates power to control people in modern society within knowledge, with a close link between the body and punishment.

Staff and students conform to these rules and regulations to avoid sanctions. Student’s attire is observed by both academic and administrative staff of the institutions (Figure 1). Norms are an unavoidable regime of power used to evaluate, control, and describe human behaviour. To ensure conformity to established institutional standards of formal dressing, these approved dress codes are enshrined in the institutions' prospectuses, emphasized during orientation programmes for new students, available on their websites, flagged at the major entrances of the institutions, and implemented by both academic and administrative units. Deviants who violate these dress and grooming codes are put through formal and informal constraints.

Figure 1

Fashion worn by students on the University of Port Harcourt campus.

Fashion and Social Hegemony

Fashion studies encompass diverse intellectual domains with an interdisciplinary outlook, but are not limited to sartorial practices (Kawamura, 2005). Like many sociological concepts, the concept of fashion is semantically ambiguous and has been described in various ways, in relation to concepts such as clothing, dressing, style, attire, costume, apparel, and more. This is indicative of the fact that the early beginnings of fashion were in clothing styles, as clothes and wearing apparel were the most visible elements of fashion. As a generalized phenomenon, there are multiple dimensional aspects of fashion which include clothes, shoes, jewellery, bags, cosmetics, adornments, body markers (tattoos), personal grooming, furniture, cars, names, cuisine, interior decorations, management, hair, and others. Welters and Lillethun (2018) conceptualized fashion as changing dress practices, body modifications, hairstyling, fabrics, and textiles. This broad and generalized phenomenon (Blumer, 1969; Lipovetsky, 1987) embraces both the material and non-material components of a culture of which clothing is one material aspect. Importantly, commonly-held notions of fashion have centred on fashion as clothing and dress (Brenninkmeyer in Kawamura, 2005; Craik, 1994; Davis, 1992). This study supports Eicher and Roach-Higgins's (1992) view of dress as a collection of body alterations and/or supplements. Dress is operationalized in the study as “an intentional and unintentional modification of appearance, what people do to their bodies to maintain, manage and alter appearance” (Reddy-Best, 2020). “Clothing” is used interchangeably with “dress” as a generic term for dress, grooming, and personal adornments.

The relevance of the phenomenon of fashion in sociological studies can be observed in its intersection with subject matters of micro and macro sociological analysis (Crane and Bovone, 2006; Aspers and Godart, 2013). Sociological studies in fashion identify social control as one of the key themes in academic insights into the social process of fashion (Horowitz, 1975) in which social structures are produced and maintained (Aspers and Godart, 2013). Fashion was viewed as a status marker driven by the elite in different civilizations, not restricted to the historical development of European societies (Craik, 1993).

Early beginnings of western fashion started in closed societies that limited social mobility, where sumptuary laws and social classes precluded some people from being fashionable. Sumptuary laws served the needs of the royal, noble, and rich in relation to the approved type of clothing for different members of the society, reflecting the values at that time. The juxtaposition of the social relations of fashion and the body are both central and symbolic (Entwistle, 2000; Benjamin, 1999). In negotiating fashion in tertiary institutions or formal organizations, formal institutional control is achieved through clearly written guidelines on acceptable dress and standards of appearance. Studies have shown that fashion as clothing and dress have been studied from the perspective of change (Aspers and Godart, 2013).

Taylor (2004) observed that earlier documentation of non-western/ethnic dress portrayed these as cultural artifacts. African dress was viewed as traditional and distinct from western fashion. African fashion underlines the richness and diversity of African culture with its own history and influences. Fashion is a non-verbal language that elucidates both the objective and subjective meanings of clothing behaviour, adornment and grooming within any given society (Nwauzor, 2016). Fashion is an embodied practice that portrays the body in certain ways, bolstering social cohesion and imposing group norms (Wilson, 1985). Fashion is a “flashpoint of conflicting values” in interactions across tertiary institutions in Nigeria, largely due tooverarching issues of decency and sexual harassment on campuses. Nwauzor (2011) observed that youth sub-culture fashion has been used to challenge previously held societal norms of decency and modesty. Although fashion attempts to balance contradictions, such as attractiveness and modesty, it must still be worn according to the rules and conventions governing it. As an intellectual space where values are formed, the university is a character-moulding institution.

Social hegemony in the Nigerian university system refers to the cultural dominance and authority of the university management on dress and adornment practices over members of the university community. This authority is exercised to curtail the pervasive influence of foreign/pop culture of fashion. The university management holds the authority as a space for instilling values and good character traits in accordance with the government policy on university education in Nigeria. The National Policy on Education (2004) as cited by David, David, and Okolie (2021), stipulates that the aim of university education includes, among other things, value orientation for human capital development.

The Banality of Dress norms/codes

Extant literature has shown that most institutions adopt dress codes as a mechanism for controlling students, employees, and members' dress and appearance standards (Fayokun, Adedeji and Oyebade, 2009; Pogoson, 2013; Chartered Institute of Bankers, 2014; Friedrich and Shanks, 2021; Nath et al, 2016; Pomertanz, 2007). Dress codes originate from peoples' world views, outlooks, cultures, values, and norms, and are dependent on occasion, time, rationale, and issue. The Holdeman Mennonite community imposed dress codes to restrain females’ physical bodies to attain a perceived sexual reputation and ensure commitment and conformity to religious beliefs and values (Arthur, 1997). Formal organizations institute official appearance standards for employees to establish corporate branding, role professionalization, and corporate identity, and to ensure a healthy and safe professional environment (Nath et al, 2016).

Dress codes can function as regulatory policies that underlie an educational institution's core values by raising its reputation, meeting standards of dress and sartorial behaviour, and promoting discipline or indicating of the type of profession (Lunenburg, 2011; Sequeira et al. 2014). Educational institutions, particularly universities, adopt dress standards to emphasize their role in shaping students and, by implication, graduates who would be found worthy not only in learning but also character. This stance reflects the seriousness, dignity, and character-moulding nature of the academic environment. In addition, dress codes contribute to potential career grooming and forestall students’ inappropriate use of body supplements. Foreign studies on dress codes have primarily focused on primary and high schools, as colleges or universities have been understudied in the literature (Sequeira et al. 2014).

Dress norms come in different forms, such as: written, extensive, and definite formal dress codes enshrined in student handbooks to ambiguous and unwritten norms (Nath et al, 2016). Clothing/dress norms or codes portray common expectations regarding how adults in the university community, particularly students, should appear as a standard of modesty. Dress codes symbolize the moral dimension of clothes which are firmly entrenched in peoples' social consciousness (Wilson, 1985). Dress codes refer to a set of rules/guidelines, particularly in educational institutions, that symbolize the appearance standards for students.

Method

The study is based on the ethnographic analyses of dress codes at different public and private universities in Nigeria as posted on their websites. Additionally, the research incorporates participant observation and the unstructured interview method. As a lecturer at the University of Port Harcourt for the past nine years, the researcher has made close observations of students and learned their dress behaviour, both covertly and overtly. The researcher engaged with students in a series of natural conversations on fashion and sartorial decrees without predetermined questions. This information in the form of dress code was either published in the students' handbook or displayed at the major entrances of these institutions (Figure 2). Generally, many public and faith-based private universities in Nigeria have dress code policies. Previous studies focused on indecent dressing on Nigerian campuses, the moral or legal implication of dress codes, and negative media influence on students' fashion, especially girls, within one or two geopolitical zones. This study examined the dress codes of six universities, including private and public. The six universities were drawn from each of the six geopolitical zones in the country for a more inclusive representation and insightful research. The research adopted a purposive and convenience sampling approach in the selection of universities. The major criteria or rationale for selection are region and availability of a student's dress guidelines. The selected universities include Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria (federal), University of Maiduguri (federal), Covenant University, Ota (private), University of Port Harcourt (federal), Godfrey Okoye University, Enugu (private) and Benue State University, Makurdi (state-owned). Three federally owned universities were selected because the University of Maiduguri is the only university in Northeast Nigeria with a dress code guideline. Another crucial observation made in the course of selection is that there are more private universities situated in the southern part of the country, particularly in the Southwest.

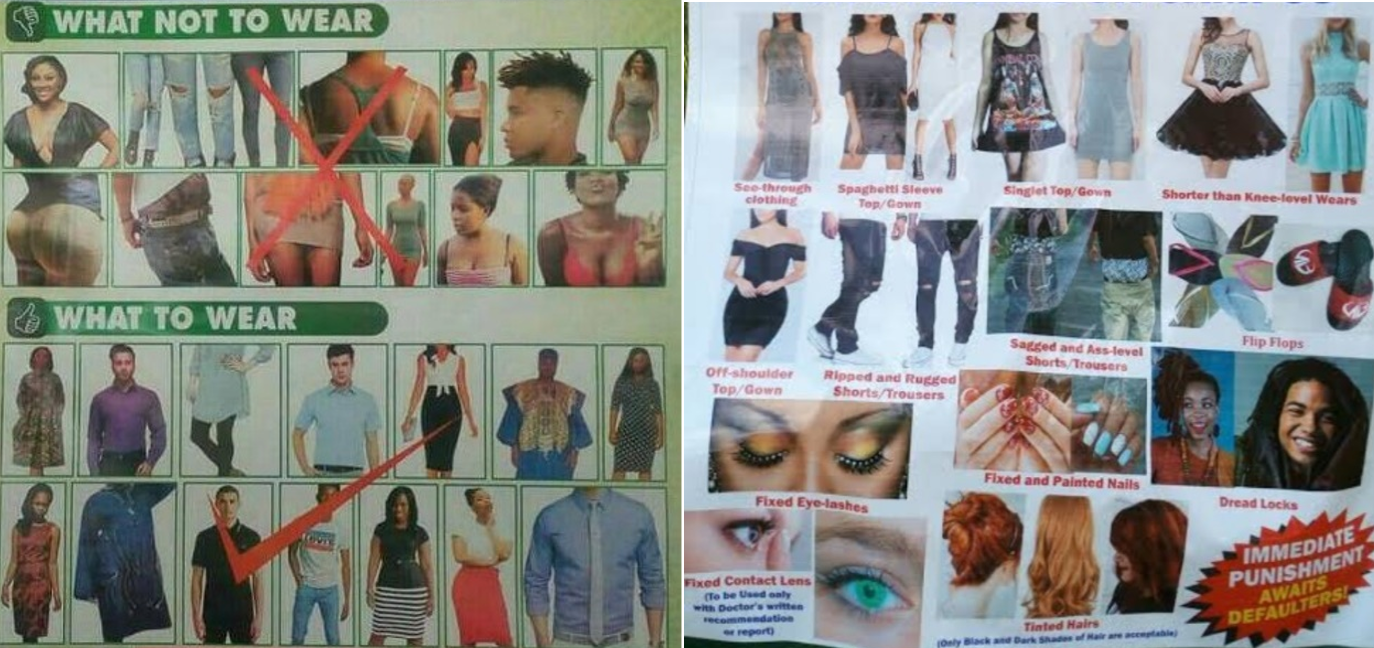

Figure 2

A display of some approved and prohibited dress on the campuses retrieved from the websites of the University of Port Harcourt, Benue State University, Makurdi, and the Godfrey Okoye University.

The study relied heavily on secondary data, which was analyzed descriptively, qualitatively, and illustrated by images.

There is neglect in academic analysis of dress from the fashion studies perspective. Based on the guidelines on body modifications and supplements available in the six selected universities, the findings were produced. The study explored the basic characteristics of each institution in relation to their dress and appearance standards. We begin the analysis with clothing norms as visual markers of the social boundaries of fashion which is the main concern of the study. For an analytical result, the study isolated sections of institutional dress guidelines that focused on the theme of clothing norms as modest and decent dressing standards. Discussions focused on institutional interactions that encourage dress conformity, institutional surveillance, and threat of consequence influence on self-discipline. It explains fashion as a system of exerting influence through control of the social body as reproduced in tertiary institutions.

Findings: Institutional Characteristics and Dress and Appearance Standards

Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) is a public-owned federal university named after Nigeria's first prime minister and the late Sardauna of Sokoto. A pioneering university in the North was established in 1962, having been formed from some existing institutional structures, particularly the Ahmadu Bello College for Arabic and Islamic studies in Kano. The university is situated in Zaria, Kaduna, a state under the dual system of the Sharia law and common law. The 17th edition of the ABU, Zaria undergraduate student handbook for the 2019/2020 session, part-XVI, page 98, stipulates the dress code guidelines of the university. The university does not tolerate any form of indecent dressing within its community. It is located in the Northwest geo-political region of the country.

The University of Maiduguri is a second-generation, public-owned federal university established in 1975. The university is located in the heart of Maiduguri, a border town in the Northeast geo-political zone within the administration of the penal code system of the Sharia law. It does not have a published dress code guideline, but specifies on its website the various dress and appearance standards expected of its students.

The University of Port Harcourt (Uniport) is another second-generation, public-owned federal institution established in 1975, formerly a college campus of the University of Nigeria. It is located in Choba, the outskirts of Port Harcourt, on the East-West road axis in Rivers state, within the South-South geo-political zone. The University of Port Harcourt’s dress code guidelines, as found on posters displayed at the major entrances of faculties and offices, identify certain forms of indecent dressing. Also, the school of General Studies Student Handbook under the ethics committee's code of conduct for students states that “students must dress decently at all times” (and in line with the faculty/college prescribed dress code where necessary).

Benue State University is a public-owned state university in Makurdi, Benue state, established in 1992. It is located in the North-Central geo-political zone of Nigeria. Like the University of Maiduguri, Benue State University has its dress code guidelines posted on its web page. The university’s dress code portrays images of what students should or should not wear in addition to a written guideline.

Godfrey Okoye University is a privately owned university founded by the Catholic Diocese of Enugu in 2009. It is the first university owned by the Catholic Church in Africa and is located in Enugu town, drawing students from the South-East geo-political zone. Information on its webpage highlights images of “prohibited dresses and make-up for students on campus.”

Covenant University is another privately owned university of the Living Faith Church (Winners Chapel), founded in 2002 at Canaanland, Ota, Ogun state. Being a Christian mission university, Covenant University students and activities are guided by the Christian ethos. The university draws students from the South-West geo-political zone. It is the only university among the six selected universities with a detailed and extensive dress code guideline enshrined in the students' handbook. The current edition of the students' handbook for the period 2019-2022 underscores the premium that the university places on decent and modest dressing. Chapter 7:6 extensively outlines the dress and appearance standards of male and female students.

Out of the six selected universities, four — namely, the University of Maiduguri, ABU, Covenant, and Godfrey Okoye — ensured a strict enforcement of the rules for certain reasons. UniMaid and ABUs location in predominantly Muslim societies guaranteed the enforcement of Islamic principles and dress codes within the universities. On the other hand, Godfrey Okoye and Covenant universities, by virtue of their private ownership by faith-based organizations, were controlled in accordance with their religious ethos of morality and modest fashion.

Due to the nature of the University of Port Harcourt and Benue State University as public institutions situated in the South-South and North-Central regions of the country, where the majority of students are Christians, they are influenced by prevailing fashion preferences.

Modest and Decent Dressing

What constitutes modest or decent dressing is not absolute but determinable by the socio-cultural attributes of a people (Ben, 2019) and varies across cultures, religions, and societies (Adewunmi, 2011). Modesty refers to the quality of propriety in dress, speech, or conduct. There is no single parameter for measuring modest or decent dressing. Lewis (2013) examines the “intersection of modesty in modern fashion with or without religion.” The book offers a divergent view of modesty as either a form of female religious action or a notion that extends beyond religion. Data indicated that the dress code guidelines of the six selected universities emphasized modest and decent dress. Commonalities exist in their respective interpretations of modest and decent dressing but are largely dependent on the core values of the institutions.

All the institutions prohibited sartorial expressions and dresses that are transparent and see-through, expose sensitive body parts, tattered and crazy jeans, public exposure of underclothing, unkempt appearances, and plaiting, braiding or weaving of hair by male students as indecent dressing. The guidelines of ABU and Uniport are verbatim, except for one item that is added to the guidelines of ABU. The published dress code guidelines of Ahmadu Bello University and the University of Port Harcourt were liberal. Benue State university had an even more liberal dress code than the rest, allowing sleeveless shirts or gowns and knee length dresses prohibited in other institutions. Although there is a similarity in the published dress and appearance standards of ABU, Uniport, and BSU, it is pertinent to note that, in principle, these rules are stringently enforced at ABU. Furthermore, the university management is mostly controlled by Muslims. The University of Maiduguri's perspective of modest and decent dressing is a blend of corporate and Islamic dress patterns, as portrayed in the pictorial messages.

Godfrey Okoye University and Covenant University particularly isolated certain prohibited body supplements and modifications, including tattoos, two or more earrings on one ear, big and dropping earrings, artificial nails, use of nail polish, coloured hair weaves or braids different from the girls' hair colour, and heavy make-up. Other prohibited items include anklets, waist beads, toe rings, body piercings, keeping beards, afro-looking or bushy hair, dreadlocks or treated hair by males, wearing of jewellery by males, possession and wearing of cauldron, chinos, or any jean or jeans-like material, contact lenses, and artificial eyelashes.

Institutional Interactions that Encourage Dress Conformity: The Disciplinary Power of Knowledge

This study explains institutional interactions that encourage dress conformity as strategies and techniques of social power relations in the university. Disciplinary power or power to control students' behaviour lies in their knowledge of the approved dress and appearance norms and sanctions. Dress code guidelines constitute a vital part of the process of training students whom the university would later reward for being found “worthy in character and learning.” There were equal sanctions for defaulting students, with UniMaid, ABU, Covenant, and Godfrey Okoye adopting more stringent measures to forestall deviance. Dress code guidelines for the selected universities are published on their webpage, university bulletins, and students' handbooks. Messages are displayed at the entrance of the university, administrative blocks, colleges, faculties, and departments. New students become acquainted with the existing guidelines on dress and appearance standards at the point of registration by the Department of Student Affairs. The orientation programme forms part of the character-moulding activities in the university, where the core values are inculcated in new students. Additionally, the university matriculation ceremony provides another platform where matriculating students formally pledge to abide by all rules and regulations guiding student behaviour in the university. Dress code of Covenant University and other faith-based private universities symbolizes religious standards that emphasize the internalization of its dress code culture as a desideratum for a student's pleasurable academic pursuit. Sanctions reflect an influential tool to ensure conformity to standards. The University of Maiduguri, ABU Zaria, and Benue State University, Makurdi have no published sanctions for defaulters on their websites or in their handbook. Godfrey Okoye only noted that immediate punishment awaits the defaulter. Sanctions for defaulting students in Uniport range from counselling to sending away the defaulter from the lecture room, examination halls, or the academic area where such appearance is prohibited, and appearance before a disciplinary panel. In addition to these, Covenant University sends a warning letter to the erring student, writes the parent of the erring student, invokes a suspension on the unrepentant student after at least two warnings, and lastly, expulsion. Power relations between university administration and students assist in normalizing the character of obedience to constituted authority through the regulation of their daily sartorial behaviour patterns. A general observation of the conformity of students dressing to approved standards in the selected universities revealed a high and relative level of conformability. This shows that students of ABU, UniMaid, Covenant, and Godfrey Okoye University were highly conformable to the norms due to a high degree of repression. In contrast, students of Uniport and Benue State University relatively conformed to their approved dress codes, probably due to their liberal nature and environment. Furthermore, the management of these institutions has not demonstrated the agency to enforce the dress codes.

Institutional Surveillance and the Threat of Consequence Influence Self-Discipline

The phenomenon of surveillance in contemporary societies with the aid of camera devices has become normalized as part of everyday life, internalized, and supported by different institutions. The panopticon is a schema that facilitates the exercise of disciplinary power through surveillance (Gallagher, 2010). Researchers tend to describe schools as “panoptic spaces” (Gallagher 2010, Bushnell 2003, Blackford 2004, Perryman 2006) a “prison in disguise” (Barker et al, 2010 and Hall, 2003) and an enclosed place (Dolgun 2008 cited in Ceven et al, 2021) with a culture of strict discipline and surveillance. Foucault identifies a correlation between school and prison, where prisoners are treated like children that must obey the decisions of their parents. The university instils, socializes, dominates, and teaches its students the imperative of obedience to rules and regulations.

Clothing norms are mechanisms of insidious control and disciplinary power exercised through routine panopticon monitoring by academic and administrative staff. Institutional surveillance is the hallmark of enclosed places with a religious colouration. Although ABU and UniMaid are public institutions, the dominant religious climate influences the moral standards and boundaries applicable to the universities. Covenant and Godfrey Okoye University, by virtue of their mode of ownership and standard method of operation, routinely monitor students dressing behaviour on campus. The mental picture of ones’ behaviour permanently under surveillance by the panoptical lens of the university ingrains self-discipline among students.

Students inculcate self-discipline in their negotiation of fashion towards institutional control. Foucault (1995) views discipline as the power to control students' dress and appearance through surveillance, and as a conscience-building mechanism that ensures that dress codes or norms are obeyed. Adherence to dress codes is a reflection of panoptic observation practice (Foucault 2014 in Ceven et al, 2021) characterized by internalized norms, volitional, and social, ideological, or religious influence. Disciplinary power works as training, monitoring, and examination. Foucault (1995) notes that there is a possibility of resistance to power, but the knowledge of the probable consequence such action would evoke may lead to self-discipline. Sometimes the rules are made outlining the consequences of deviance; however, they may not be implemented.

Conclusion

From a sociological viewpoint, this article has examined dress or clothing as a visible element of fashion with social control as one of the major themes of the social process of fashion.

The paper focused on the individual characteristics of the appearance standards in the selected universities, examining their constructions of modest/immodest and decent/indecent dress. The Foucaultian framework of Discipline and Punishment was applied in the analyses of the following variables: institutional interactions that encourage dress conformity and institutional surveillance, and the threat of consequence on self-discipline.

The main findings of the analysis the study’s contributions are highlighted below. It was observed that the dress and appearance standards and students' sartorial choices and behaviour were largely influenced by the nature, environment, and core values of the study institutions. Although universities award degrees on the premise that the graduate had been found “worthy in learning and character,” the study revealed that four universities handled this aspect of character shaping with dexterity. Secondly, the study institutions’ emphasis on modest and decent dress indicates a strong response against indecent dressing on campus. This supports earlier research on what constitutes indecent dressing (Egwim, 2010, Omede, 2011). What differed was the respective institution's interpretation of modest and decent dress.

Thirdly, regarding the institutional interactions that encourage dress conformity, the disciplinary power of knowledge, as characterized by Foucault, aptly describes it as the technique of power relations within the university. The process of students' socialization enhances their internalization of the appropriate dress standards. Moreover, students subscribe to these guidelines to avoid sanctions. Finally, the paper notes that institutional surveillance is a conscience-building mechanism that reflects the culture of strict discipline reminiscent of educational institutions, particularly those with a religious background. Covert surveillance and monitoring of students’ dress and sartorial behaviour promote self-discipline among students. This shows that not only does institutional surveillance influence self-discipline, but the threat of consequence could produce either embodied conformable or defiant students.

This study has contributed to existing knowledge by examining the notion of fashion as dress and adornment practices that serve as sites for institutional control of the clothing behaviour of adults from a sociological perspective. For further research, attention should be given to the implementation of dress codes in different universities.

References

Adewunmi, Bim (2011). Faith-based fashion takes off online. The Guardian. Retrieved 03/10/2022.

Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) 2019/2020 undergraduate students handbook, Zaria,Kaduna state.

Aspers, P. and Godart, F. (2013). Annual Review Sociology. Doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145526 Retrieved 07/05/2022

Arthur, L.B. (1997). ‘Clothing is a Window to the Soul: The Social Control of Women ina Holdeman Mennonite Community. Journal of Mennonite studies Volume 15, 1997.

Arthur, L. B. ed. (2000). Undressing Religion: Commitment and conversion from a cross-cultural perspective. Berg Fashion Library.

Barker, J., Alldred, P., Watts, M., and Dodman, H. (2010). Pupils or prisoners? Institutional geographies and internal exclusion in UK secondary school. Area 42 (3), 378-386.

Ben, Hannes (2019). Modest fashion, major opportunity. Locaria. Retrieved 03/10/2022.

Benjamin, W. 1999. The Arcades Project. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press

Benue State University Makurdi https://www.bsum.edu.ng

Black, Prudence and Findlay, Rosie (2016). Dressing the Body. Cultural Studies Review Volume 22 number 1 March 2016.http://dx.doi.org/10.5130/csr.v22i1.4907

Blackford, H. (2004). Playground panopticism: Ring-around-the-children, a pocketful ofwomen. Childhood. 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568204043059

Braudel, F. Civilization and Capitalism 15th – 18th Century (Braudel 1956), Vol. I (California: University of California Pres, 1992), p. 311.

Bushnell, M. (2003). Teachers in the school house complicity and resistance. Educationand Urban Society 35(3), 251-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124503035003001.

Calefato, Patrizia (2004). The Clothed body. Oxford: UK.

Ceven, G., Korumaz, M. and Omur, V.E. (2021). Disciplinary power in the school: the panoptic surveillance. Educational policy analysis and strategic research Volume 16 (1). DOI:10.29329/epasr2020.334.9

Chartered Institute of Bankers (2014). Code of Conduct in the Nigerian Banking industry.

Covenant University 2019-2022 Student Hand Book, Otta, Ogun State.

Craik, J. 1993. The Face of Fashion: Cultural Studies of Fashion. London: Routledge

Crane, D. (2000). Fashion and Its Social Agendas. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Crane, D, Bovone, L. 2006. Approaches to material culture: the sociology of fashion and clothing. Poetics 34:319–33

Dairo, M. (2023). Nigerian university dress codes: markers of tradition, morality andaspiration. Journal of African Cultural Studies. Routledge.

David, I., David, E.G.O, & Okolie, U.C. (2021). University education and its impact onhuman capital development in Nigeria. Volume 24 No. 1 Anno XXIV 1-2021s

Egwim, C. (2010). Indecent Dressing Among Youths. http://www.es/networld.com/webpages/features Retrieved September 26, 2022.

Entwistle, J. 2000. The Fashioned Body. Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge, UK: Polity

Entwistle, J. 2015. The fashioned body. London: John Wiley & Sons

Fayokun, K. O, Adedeji, S.O. and Oyebade, S.A. (2009) “Moral crisis in higherinstitutions and the dress code phenomenon” US-China Education Review, Volume 6, No.2 (Serial No.51)

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish, the birth of prison. (A Sheridan, Trans). Vintage books, A division of Random House Inc.

Friedrich, Jasper and Shanks, Rachel (2021). ‘The prison of the body: school uniforms between discipline and governmentality’. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural politics of education. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2021.1931813 Accessed 24/03/2022.

Gallagher, M. (2010). Are schools panoptic? Surveillance and Society 7(3/4), 262-272. https://www.surveillance-and-society.org

Godfrey Okoye University https://www.gouni.edu.ng

Hall, N. (2003). The role of the slate in Lancastrian schools as evidenced by their manuals and handbooks. Paradigm 2 (7), 46-54.

Hansen, K.T. 2004. The World in Dress: Anthropological Perspectives on Clothing, Fashion, and Culture. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2004. 33:369-92 doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143805. Accessed 06/07/2022

Honkatukia, P. and Keskinen, S. (2018). The social control of young women’s clothing and bodies: A perspective of differences on racialization and sexualization. Ethnicities 2018, Vol. 18(1) 142–161. DOI: 10.1177/1468796817701773

Hume, L. ( ). Dress and religion. Doi: 10.5040/9781474280655-BG006

Hume, L. (2013). The religious life of dress: Global Fashion and faith. London:Bloomsbury Academic.

Horowitz, R.T. (2009). ‘From Elite Fashion to Mass Fashion’. European Journal of Sociology. Cambridge University Press.

Iruonagbe, C.T, Imhonopi, D., & Egharevba, M.E. (2015). Higher education in Nigeriaand the emergence of private universities. International Journal of Education and Research 3(2), 49-64.

Jenkins, Tania M. (2014). Clothing norms as markers of status in a hospital setting: A Bourdieusian analysis. London: Health.

Johnson, K.S., Lennon, J. and Rudd, N. (2014). “Dress, Body and Self: Research in thesocial psychology of Dress”. Fashion and Textiles 1(1) : 20 Doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-014-0020-7

Kawamura, Y. (2005).Fashion-ology: An Introduction to Fashion Studies. New York: Berg Press

Lipovetsky, G.1987(1994).The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. 276 pp.

Livsey, T. (2017). Nigeria’s university age: reframing decolonization and development. Oxford: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Can schools regulate student dress and grooming in school. Focus On Colleges, Universities, and Schools, 5(1), 1-5.

Lurie, A. (1981). The Language of Clothes. Random House, New York. Accessed 02/07/2022.

Nath, V., Bach, S. and Lockwood, G. (2016). Dress codes and appearance norms at work: Body supplements, body modifications and aesthetic labour. www.acas.org.uk/researchpapers

Omede. Jacob, (2011) “Indecent Dressing on Campuses of Higher Institutions ofLearning in Nigeria: Implications for Counseling” Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies (JETERAPS) 2 (4): 228-233 © Scholarlink Research Institute Journals, (ISSN: 2141-6990).

Perryman, J. (2006). Panoptic performativity and school inspection regimes: Disciplinary mechanisms and life under special measures. Journal of Education Policy 21(2), 147-161. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500500138.

Pomertanz, Shauna (2007). “Cleavage in a tank top: Bodily prohibition and the discourseof school dress codes”. Alberta Journal of Educational Research 53 (4) : 373 – 386.ProQuest 228639180.

Reddy-Best, K. (2020). Dress Appearance and Diversity US society. Press book publishers.

Sequeira, A. H., Mendonca, C., Prabhu, K., & Narayan Tiwari, L. (2014). A Study onDress Code for College Students. Mandeep and Prabhu K., Mahendra and NarayanTiwari, Lakshmi, A Study on Dress Code for College Students (September 29, 2014).

Simmel, G. 1904 (1957). Fashion. Am. J. Sociol. 62:541–58

Toennies, F. (1887). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft.

Tseelon, E. (1989). Communication via Clothes. Unpublished paper. Department of experimental Psychology, University of Oxford.

University of Maiduguri https:/www.unimaid.edu.ng

University of Nigeria, Nsukka. https://www.unn.edu.ng>mission-v

University of Port Harcourt (2020/2021) School of General Studies Student Handbook.

Veblen, T. 1899. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. New York: Dover Thrift. 244 pp. Wilson, E. (1987, 2004). Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, University of California Press, Berkeley, p.378.

Appendix

The Dress Code Landscape of the Six Selected Nigerian Universities

Ahmadu Bello University

No short, skimpy and revealing dresses, tight and short skirts above knee length, crazy jeans, transparent and see through, tight fitting dresses or fabrics, public exposure of underwear dresses, unkept appearances like bushy hair and beard, dresses that impair the use of laboratory coat, long and tight skirts with a slit that reveal wearer's sensitive parts, T-shirts with obscene captions, shirt without buttons or unbuttoned shirts, wearing of ear-rings by male students, plaiting and weaving of hair by males, wearing of coloured eyeglasses or bathroom slippers in the classroom (except on medical grounds) and wearing of trousers that stop between knee and ankle.

Sanctions: None

University of Maiduguri

No written dress code guidelines except pictorials. The pictorial message highlights a blend of corporate and Islamic dress patterns that cover all parts of the body except the face and hand.

Sanctions: None

University of Port Harcourt

Short and skimpy dresses e.g. Body hugs, show me your chest, spaghetti wears and dress exposing sensitive parts; Tight shorts and skirts that are above knees except for sporting purposes; Tattered jeans and jeans with holes; Transparent and see through dresses; Tight fittings e.g. Jeans, skirts, hip star, Patra, hot pants, lycra, Haller neck, etc that reveals the contour of the body; Underclothing such as singlet worn publicly; Unkempt appearances such as bushy hairs and beards; Dressings that make it impossible to wear laboratory coats during practicals or participate actively in practical; Long and tight skirt which are slit in the front or at the side which reveals sensitive parts as the wearer moves on; Wearing of T-shirts with obscene captions; Shirts without buttons or not buttoned leaving the wearer bare-chested; Wearing of ear-ring by male students; Plaiting or wearing of hair by male students; Wearing of coloured eyeglass in classroom (except on medical ground); and wearing of bathroom slippers to classroom (except on medical ground).

Sanctions:

1ST OFFENDER – To appear before the dress code and implementation committee for counselling;

2ND OFFENDER – To be sent out of the classroom, library, office, workshop, lecture theatre, etc.

3RD OFFENDER – To appear before the Students' Disciplinary committee.

Benue State University

Dress that exposes any sensitive parts of the body e.g. cleavage, chest, back, navel, thigh and armpit (clothes that reveal the armpit when hands are raised e.g. sleeveless, half sleeves; Tight fitting wears; Transparent(see through wears); Tattered jeans or ripped jeans; T-shirts with obscene inscriptions depicting immorality, hooliganism, etc; Indelible markings and body tattoos by students; Leggings trousers with short tops; Skimpy dresses e.g. spaghetti(camisole only, body hugs, strapless blouse and short; knickers; Bathroom slippers are not acceptable within the administrative and academic areas; Heavy make-ups; Sagging trousers; Wearing of earrings by male students and Combat short knickers.

Sanctions: None

Godfrey Okoye University

Prohibited dresses and make-ups for students on campus include: See through clothing; Spaghetti sleeve top/gown; singlet top/gown; Shorter than knee-level wear; Off-shoulder top/gown; Ripped and rugged shorts/trousers; Sagged and ass-level shorts and trousers; Flip-flops; Fixed eye-lashes, Fixed and painted nails; Dreadlocks; Fixed contact lens (to be used only with doctors written recommendation or report) and Tinted hairs.

Sanctions: Immediate punishment awaits defaulters.

Covenant University

Dress Code for Female Students

1. Female students must be corporately dressed during normal lectures, public lectures, special ceremonies, Matriculation, Founder’s Day, Convocation and examinations. To be corporately dressed connotes a smart skirt suit, skirt and blouse, or a smart dress with a pair of covered shoes. Casual wear is not allowed during University assemblies.

2. All dress and skirt hems must be at least 5 -10 cm (2-4 inches) below the knees.

3. Female students may wear decent “native” attire or foreign wear outside lecture and examination halls.

4. The wearing of sleeveless native attires or baby sleeves and spaghetti straps without a jacket is strictly prohibited in the lecture rooms and the University environment.

5. Any shirt worn with a waistcoat or armless sweater should be properly tucked into the skirt or loose trousers. It should never be left flying under the waistcoat/armless sweater. The waistcoat/armless sweater must rest on the hip. “Bust coats,” terminating just below the bust line are not allowed. However, shirts with frills are allowed.

6. Jersey material tops are not allowed for normal lectures and other University assemblies.

7. Skirts could be straight, flared or pleated. Pencil skirts and skirts with uneven edges are not allowed. Lacy skirts are better worn to church. None should be tight or body- hugging.

8. The wearing of dropping shawls or scarves over dresses or dresses with very tiny singlet-like straps (spaghetti straps) is strictly prohibited in the Chapel services, lecture and examination halls and in the University environment.

9. The wearing of strapless blouses or short blouses that do not cover the hip line is strictly prohibited in the lecture and examination halls and the University environment.

10. The wearing of over-clinging clothing, including body hugs clothing made from a stretchy or elastic material such as a condom, bandage skirts, leggings and joggings is strictly prohibited in the lecture and examination halls and in the University environment.

11. The wearing of revealing blouses, especially low-cut blouses and the type of blouse that does not fall below the hip line, is strictly prohibited in the lecture and examination halls and the University environment. The wearing of ordinary transparent dresses is strictly prohibited in the lecture and examination halls.

12. The use of face-caps in the lecture rooms, examination halls, University Chapel and the University environment is strictly prohibited.

13. Wearing bathroom slippers are not allowed in the academic buildings, Library and Chapel.

14. Female students are advised to wear corporate hairstyles that are decent. Coloured attachments that are different from the student's hair are strictly prohibited at the University.

15. Female students may wear trouser suits; however, the jacket must fall below the hip line.

16. Earrings and necklaces may be used by female students, provided they are not the bogus and dropping types. The wearing of more than one earring in each ear is strictly prohibited anywhere in the University. Also, painting nails, and attaching artificial long nails are not allowed in and outside the University.

17. Wearing ankle chains and rings on the toes is prohibited at the University.

18. The possession and wearing of jeans or any jeans-like materials of any kind are strictly prohibited in the University.

19. Female students are expected to wear corporate shoes to lectures and University assemblies.

20. Sports shoes or sneakers may only be worn outside the Chapel, lecture and examination halls.

21. Piercing of any part of the body, other than the ear (for earrings), is strictly prohibited. Any other piercing done before admission into the University shall be declared during the first registration in the first year.

22. Tattooing of any part of the body is prohibited. Any tattoo done before admission into the University shall be declared during the first registration in the first year.

23. Skirt slits should not be unnecessarily long and should not expose any part of the body from the knees upwards.

24. Wearing short trousers of any kind, tights, etc., to the lecture halls, Chapel services, and examination halls is strictly prohibited.

25. Wearing of boob tubes and camisoles under jackets should be done properly. No part of the chest should be revealed.

26. Wearing tops, shirts or T-shirts with indecent inscriptions and other forms of indecent words is not allowed anywhere in Covenant University and Canaanland.

Dress Code For Male Students

Male students are expected to dress corporately in the lecture halls, examination halls and University assemblies. To be corporately dressed connotes wearing a shirt and necktie, a pair of trousers, with or without a jacket, and a pair of covered shoes with socks. The tie knot must be pulled up to the top button of the dress shirt.

1. For national days such as Independence Day, the national dress code may be observed. Any shirt with indecent inscriptions or any sign with hidden meaning is strictly outlawed.

2. Bandless trousers must never be worn without suspenders. Singlets and shorts above the knee are not allowed.

3. No male student is allowed to wear jumpy trousers i.e. trousers above the ankle in the University.

4. Folding, holding and pocketing of one's tie along the road, lecture halls, University assemblies, etc., is strictly prohibited in the University.

5. Wearing a tie with canvas is not allowed in the University environment. Jerry’s curls and treated hair are strictly prohibited.

6. Male students may wear “native” or traditional attire outside lecture hours and examination halls, especially during the weekend.

7. No male student is allowed to wear scarves, braided hair, earrings and ankle chains in the University.

8. Wearing long-sleeved shirts, without buttoning the sleeves is not allowed.

9. Shirt collars should not be left flying while collarless shirts are not allowed.

10. Shirts must be properly tucked into the trousers.

11. The practice of pulling down one’s trousers to the hip line (Sagging) is prohibited.

12. Students are advised to have low-cut hair that is combed regularly. Afro-looking or bushy hairstyle is strictly prohibited. Male students are also expected to be clean- shaven, as the keeping of long beards is prohibited. In addition,the use of clippers should be restricted to the barbing salon.

13. The possession and, or wearing of corduroy, chinos, Jeans or Jeans-like materials of any kind is strictly prohibited in the University environment.

14. Wearing slippers, short knickers,and tight trousers is strictly prohibited outside the Halls of Residence.

15. The use of face caps in the lecture halls, examination halls and University Chapel is strictly prohibited, except for sports and other related events.

16. Piercing of any part of the body is prohibited. Any piercing done before admission into the University shall be declared during the registration in the first year; failure of which appropriate sanctions shall be applied.

17. Tattooing on any part of the body is prohibited. Any tattoo done before admission into the University shall be declared during the registration in the first year.

18. Jewellery such as neck chains, hand chains, bracelets finger and toe rings, and ankle chains are prohibited for male students.

19. Wearing slippers and sports shoes, tennis shoes, sneakers, or canvas shoes is not allowed in lecture and examination halls.

20. Students are advised to avoid cutting worldly hairstyles like Richo, all back, punk etc. All male students are also expected to be clean-shaven, as the keeping of beards is prohibited. In addition, the use of clippers should be restricted to the barbing salon.

21. Slashing of eyes, wearing earrings, and putting a chain on legs are strictly prohibited on and outside the campus.

Sanctions:

1. Erring students shall be sent out of the Lecture Room, examination halls or the academic area where such is not allowed at the time.

2. A warning letter shall be issued to the erring student and a copy of the letter shall be filed in his/her personnel file in the University/Department.

3. The parents/guardians of the erring student may be informed in writing, accordingly.

4. The student shall be suspended from the University if unrepentant, subject to (1), (2) and (3) above. A student is considered unrepentant of the bad dressing habit if he or she has been warned of the offence up to at least two times.

5. Repeated cases after two warnings or Three (3) weeks ofsuspension shall attract suspension for one session or outright expulsion as the case may be.

Source: Compiled from the dress code guidelines of the six selected universities.

Author Bio

Adaku Agnes Ubelejit-Nte (née Nwauzor) is an academic with research interests in fashion, urban, women, and gender studies. She obtained a PhD in Urban Sociology in 2011 from the Department of Sociology, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria, where she has been teaching since 2014. Her PhD thesis, titled “The New media and Social Change: A Study of the Changing Patterns of Fashion in Six Selected Nigerian Universities” won the National Universities Commission’s Best Doctoral Thesis Award in the Social Science Discipline within the Nigerian University system during 2011. Adaku is a member of local and international organizations especially; Research Committee on Women and Gender in Society of the International Sociological Association, (RC 32, ISA) Research Collective for Decolonization of Fashion (RCDF) and Dress and Body Association (DBA).

Article Citation

Adaku, Agnes Ubelejit-Nte. “Clothing Norms in Nigerian Universities: Negotiating Fashion Towards Social Hegemony.” Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-26, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS050109

Copyright © 2024 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)