Dear Diary, This is My Gender Today: Scrapbooking Gender-Variant Dressed Identities as a Vehicle for Queer Empowerment

By Mia Yaguchi-Chow

DOI: 10.38055/UFN050102

MLA: Yaguchi-Chow, Mia. “Dear Diary, This is my Gender Today.” Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-28. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050102

APA: Yaguchi-Chow, M. (2025). Dear Diary, This is my Gender Today. Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies, 5(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050102

Chicago: Yaguchi-Chow, Mia. “Dear Diary, This is my Gender Today.” Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2025): 1-28. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050102

Volume 5, Issue 1, Article 2

Keywords

Gender identity

Gender expression

Queer community

Arts-based research

Scrapbooking

Abstract

The gender binary is constantly weaponized against queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming individuals, limiting their self-expression and risking their safety—but transphobia affects more than just queer people. Dear Diary, This is My Gender Today is both an active dialogue and expanded discourse of gender identity expressed in everyday dress. Reflecting on our queerness and experiences often brings mixed emotions, but it is important that our narrative not be overshadowed by struggle, tragedy, or violence—we also deserve joy and self-celebration. This project both highlights and fills gaps within gender discourse, fashion studies, arts-based research, and more by contributing self-authored arts-based stories as told by members of the queer community in scrapbook entries featured in the final zine, Dear Diary Volume I. Scrapbooking is an effective method for bringing community together and creating community in its result, for facilitating queer joy and sharing personal examples of what it is, for developing one’s knowledge of self to a greater degree, and lastly—what exists independently and as a culmination of these three themes—for empowering the queer community. Perhaps readers connect with our plights in body image or celebrations of culture, and gender just happens to play a significant role in it for many. At the very least, I hope everyone can empathize with our joy, and for us, our joy just happens to be queer. Memories fade but the feeling of transness is forever. And it is this feeling that is the most important part of these entries, not just the way they look, or the way we look.

Introduction

The gender binary is constantly weaponized against queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming individuals, limiting their self-expression and risking their safety—but transphobia affects more than just queer people. As of September 2024, 123 anti-trans bills are currently active across the United States, 45 of which having already been passed (translegislation.com). Gender-variant individuals are at risk within Canada too, with Conservative party leader Pierre Poilievre wishing to ban trans athletes from women’s sports and change rooms (Armstrong and Smellie 2024), meanwhile those who have been known to pose the most risk in women’s bathrooms, for example, have been cisgender men (Taylor 2021). Despite this, many cisgender women still fear gender-variant individuals; even hatefully mistaking “masculine” cisgender women such as Olympic boxer Imane Khelif as anything but the cisgender woman that she is, putting cisgender woman at risk from transphobia, too (Wilson 2024). With such emphasis on troubling stories, it can be easy to forget to celebrate our joy. With Dear Diary, I asked: how can we center this joy? How can we center queer joy? And how can Dear Diary ensure this joy is truly felt and shared?

Readers will learn more about the project’s literary, theoretical, and creative development, how scrapbooking and zines can be employed as valuable academic research methods, the findings of the research via participants’ scrapbook entries and interview responses. The paper then concludes with a reflection of the project. Free from the limitations of the written word, participants used scrapbooking and other arts-based methods to better understand and communicate their embodiment of gender through self-fashioning. With the publication of the final zine that encompasses their scrapbook entries and interview quotes, this project amplifies real queer voices and queer joy with the hope that readers will feel inspired to self-reflect on their relationships with gender and fashion and realize we all have more in common than we think. Kicking off the beginning of the study, my research question was, “In what ways is scrapbooking an effective method for understanding one’s relationship between gender and fashion?” This project has proven scrapbooking to be an effective method for building a deeper understanding of one’s relationship between gender and fashion based on the positive impact it left on all participants, inviting readers to contribute to a greater consciousness of deeper connections to ourselves and how we share it with the world.

Research Context

Although Dear Diary was pursued within the context of academia, the top priority was community benefit. Embedded with resistance, almost every part of this project—from the foundational methods to this paper—is deliberately disruptive in nature. This section focuses on the interrogations with literary explorations, along with personal experiences, that contributed to the foundation of Dear Diary Volume 1.

Literature Review

Pulling from a variety of sources from queer theory, self-fashioning and identity, arts-based research, art philosophy, and more, referenced authors interrogate themes of embodiment, navigating society through dress, and queer cultures and identities, both independently of and in relation to each other. It is through the synthesis of diverse literature that Dear Diary could flourish in multifaceted ways. This section highlights key literary citations and how they influenced the development of the project.

Identities are incredibly nuanced—it can be challenging to find one term to wholly represent diverse experiences. That said, the term “gender variance” to describe these multifaceted embodiments of gender acts as a theoretical framework in and of itself. Inspired by Jack Halberstam’s Trans* (2018), the use of the term “variance” is a key theme in my research as it aims to showcase a participant’s own variability through varied methods of reflection. Not all participants identified as trans or non-binary, in fact, cisgender people were also encouraged to participate—but “variance” beyond labels remains. In Trans*, Halberstam puts creative words to the nuanced trans experience, such as their own, that offered inspiration for the overall thematic approach to Dear Diary.

Many academic authors explore embodiment in their respective ways in the field of fashion studies, such as Ellen Sampson, Sophie Woodward, and Ben Barry; however, the embodied knowledge sought in this project comes directly from participants through their scrapbook or journal entries that no prior study can accurately depict more than the participant themselves. Although traditional research methods offer unique and valuable insights, I ask: what else can be extracted when participants creatively reflect and engage with their identities through alternative methods? A study called Enclothed Cognition explored how participants’ behaviour would change when dressed in a white lab coat, based on whether the garment was described by the researchers as being associated with “medical doctors” versus “artistic painters” (Hajo and Galinsky 920). Findings were extracted primarily from observational methods, and I was interested in what connections in participants’ own minds led to their interpretations and behaviour. This interest was implemented into the design of Dear Diary.

Embodied knowledge can also inform relationships between the wearer, their clothes, how they think others will perceive them, and how they then express themselves (Woodward 2007). Ellen Sampson explored embodiment in Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear (2020) through the symbiotic and cognitive relationship between shoes and their wearers by investigating their signs of wear. Dear Diary expands on research such as Sampson’s (2020) by gaining these rich insights through participants’ collections of fashion and comparing them to their present identities as told by participants themselves, situating their knowledge in a contemporary context where the relationship between gender and society continue to evolve.

Walking the Catwalk by Chris Hesselbein (2019) explored dressed bodies and embodiments through the fashion and model industries. He uses the terms, “moving beyond the ‘dressed body’ towards ‘dressed embodiment” as an acknowledgement of what lies beyond the body (367). I reinterpreted the term “dressed embodiment” as “dressed identity” to better suit the context of my research, highlighting how one’s sense of self changes when fashioned in different clothing or body modifications. The simultaneous embrace and tension between an individual, their dress, and their social context are key themes of my research for exploring how individuals navigate personal expression with and without social expectations.

Why Women Wear What They Wear by Sophie Woodward (2007) possesses a heightened relevancy to Dear Diary through its intersection of gender, dress, embodiment, identity, and more. Despite being limited to women, it is through its gender-based lens that Dear Diary could expand Woodward’s approach into a queer-centered demographic. Woodward also highlighted the importance of exploring identities “at the actual level of practice” (i.e., while dressing; in the bedroom) to researching embodiment, which participants were encouraged to do—to catch themselves making certain choices or reflections while getting dressed or being out in the world, and recording it in their scrapbooks. Woodward’s findings also displayed a time-based relationship between women and their wardrobe, which scrapbooking can also do in its ways of recording moments of the past (62). Clothing kept over time may embody different narratives relating to one’s gender identity, or even the identities of others, and may be given new meanings by its current wearer. Dear Diary applies Woodward’s academic and methodological insights into a creative, contemporary context that includes the queer community over a decade later.

Jory M. Catalpa and Jenifer K. McGuire, in Mirror Epiphany: Transpersons’ Use of Dress to Create and Sustain Their Affirmed Gender Identities (2020), explored how trans individuals “externally construct their internal image of themselves” which can manifest in a multitude of ways, including self-fashioning (50). They synthesized a collection of key themes from interviews as relevant to this construction of self-image: “First critical exposure, Tool of exploration, Vehicle to communicate, Shape the gendered body, Repetition and ritual, and Performativity” (51-56). Through their participants’ relation to these themes, insights delve into how identities and self-fashioning can be better understood together. The themes of this work directly inspired the development of Dear Diary’s scrapbooking prompts and interview questions.

Methodologically, the work of Ben Barry is an immense source of inspiration. Within Barry’s past works are projects such as Refashioning Masculinity (2018), published in Fashion Studies’ first issue, which explores the fashion influences, motivations, experiences, and disruptions of its participants through the arts-based method of producing a fashion show (13).

Researchers like Ben Barry help open the door to what new forms of research can emerge from fashion studies that do not adhere to traditional norms of academia, allowing unique voices to inform future innovations in what constitutes ‘academic’ research.

Embodiment is clearly well-known in fashion studies, so what new information may surface from approaching it through these arts-based methods, particularly as explored by participants themselves? Fashion academia is rich in explorative texts that intersect gender with fashion, embodiment, navigation of society, and queer cultures, but when we dress ourselves, we are not writing ourselves with words. We are using fashion—colours, textures, silhouettes, and more—therefore, relying on written or spoken methods would be insufficient. It was crucial that I sought creative and artistic ways to approach Dear Diary beyond just traditional academia, with respect to the great depths of nuance that its subject matter possesses.

Intersection of Art and Fashion Studies

Scrapbooking is considered a creative art form. How does it connect to fashion studies? Art philosopher Susanne Langer pondered the definition of “a work of art” in Expressiveness (1957), stating: “A work of art is an expressive form” (168); “A work of art expresses human feeling” (168); and “a work of art is a projection of felt-life” (172). Similarly, absurdist French philosopher Albert Camus defines art in Create Dangerously as “both rejection and acceptance” (32), stating that “the goal of art is to understand” (35). He says that “[art exists] in the perpetual tension between beauty and pain, human love and the madness of creation, unbearable solitude and the exhausting crowd, rejection and consent” (38). These quotes resonated with my relationship to my gender identity, how I fashion myself, and how these two elements exist in this body and world, finding that the word “art” could be replaced with “self-fashioning” in all the above quotes in context to my relationship with gender. Although connecting art with dressed embodiments is not new (Woodward 12), what this highlights is the inherent relationship between art, expression, creativity, and fashioning the body.

Arts-based researcher Ros Walling-Wefelmeyer has identified gaps in how traditional research methods are used for investigating nostalgia in their own work (98). Although still valuable, the more traditional approaches typically require the participant to not only have a clear understanding of their response but also understand it through the written or spoken word, which can be very difficult for complex studies. Given the mixed-media nature of scrapbooking, I hypothesized that participants would understand themselves more intimately after completing their entries. When used as a tool, scrapbooking can “give form” to something otherwise difficult to articulate (Walling-Wefelmeyer 3). Scrapbooking has allowed participants to consult with the “languages” that different materials and mediums speak, which allowed them to “give form” to intangible ideas that are challenging to express through traditional means.

Before social media, scrapbooking had been a popular medium for self-expression in a social setting as early as the 1910s, especially among young women (DeBauche 124, 126). Author Leslie Midkiff DeBauche (2021) explored the “memory books” of American high school seniors who had graduated between 1915 and 1922 (127), which she pointed out were “tumultuous years” historically (124). Walling-Wefelmeyer suggests scrapbooking can facilitate a confrontation and honoring of past memories, which inspire feelings of “security, control, meaning, and closure” (99). They also found that nostalgia as an outcome of scrapbooking was also found to “increase positive mood, self-regard, social connectedness, meaning in life, and self-continuity” (99). Using art as a means of confronting unknown thoughts can bring comfort between the self and the uncharted territories of the mind, cushioning oneself with the joyful practice of scrapbooking, reflected by both DeBauche and Walling-Wefelmeyer’s findings. Fast-forward decades, individuals still practice scrapbooking for similar reasons, bridging gaps between generations.

Zines can be found all over arts communities. In the city of Toronto alone, where my research is based, there is the Toronto Zine Library located at TRANZAC in the Annex, OCADU Zine Library at the Ontario College of Art and Design University, Seneca Zine Library, and more. Zines are also known for their ability to connect with like-minded people, take ownership of their own narratives in contrast to mainstream media, and create freely without the confines of expectations within authorship (Lovata 2). Historically, zines have been used between fans of science fiction, punk, and horror media to connect over common interests rarely represented in 1930s Western mainstream media (Lovata 2, 3). No matter the demographic, zines are historically known to bring people together. More contemporarily, Etengoff (2016) defined zines as “self-published, often autobiographical narratives that offer opportunities for authors to make meaning of contentious and challenging issues such as LGBTQ identity, heteronormativity, and sexual minority stress” (212), aligning them well with the concept of Dear Diary. She found that when students used zines to express themselves to others, they were able to better empathize between differences which “led to a transformative learning experience” (Etengoff 212, 217). With the hope of readers connecting personally with different aspects of participants’ entries, these academic findings on zines further support this potential outcome. Although zines were not explored as heavily as scrapbooking in Dear Diary, Etengoff’s research demonstrates great potential for what Dear Diary can later become. As explored in this section, scrapbooking and zines in and of themselves as research methods across fields are rarely used and explored, let alone just for fashion and gender. I am excited to contribute Dear Diary to this growing aspect of the field.

Methodology

Dear Diary consists of qualitative arts-based methodologies such as scrapbooking and journaling to explore gender-variant identities, day-to-day dress, and navigation of society in alternative fashions. What makes Dear Diary “arts-based research” is its use of craft (scrapbooking) to create data, which is then further analyzed using interviews and data coding instead of solely relying on traditional research methods. Not only has Dear Diary used these creative methods for critical purposes; at its core, it centered community. Dear Diary may have begun with hoppes and expectations for certain outcomes based on my research questions, but my methods were implemented knowing the final outcome would be heavily informed by its participants. Dear Diary is ultimately both arts-based and participant-led. This section highlights the design process of this research from conception to execution to completion, inclusive of ethics, recruitment, the workshop, scrapbook creation process, interviews/debriefs, the coding process that followed, ending on the final zine, Dear Diary Volume 1.

Ethics

Given the personal and heavily politicized nature of the project’s subject matter, as well as its inclusion of human participants, ethics processes are paramount; however, academia and research can feel daunting to those outside of the field. Balancing academic requirements with giving participants space to create authentically and comfortably was a high priority. This project underwent an ethics approval by Toronto Metropolitan University’s Research Ethics Board. Aspects of the project that underwent ethics review aside from the broader application form included:

1. Participant initial interest form

2. Participant consent form (once participant has been accepted into project)

3. Workshop outline

4. Scrapbooking prompts

5. Recruitment graphics and copy

6. Participant eligibility/ineligibility email templates

7. Interview questions

Within my application, a protocol for potential conflict of interest was also addressed, as there were many people in my personal network who fit the eligibility criteria, although it did not need to be consulted in the end.

Consent was essential to the ethical pursuit of this project, and participants were given opportunities to provide or revoke consent at every point of the project, especially points where they were reviewing aspects of their contributions to go into the final stages such as interview quotes and scrapbook entries. Ultimately, participants had the final say in which of their contributions were to be featured in the final zine and/or essay, with opportunities to redact any of their contributed personal information.

Recruitment

Figure 1

Two graphics as part of a greater Instagram post calling for participants. All Dear Diary graphic design is by Mia Yaguchi-Chow.

Recruitment was carried out via the above graphics (see Figure 1) posted to Instagram on my public account’s page, followed by snowball sampling through community members also sharing to their profiles and networks. The response was overwhelmingly positive in a short window of time. As a result, the majority of applicants were people I did not know personally, which proved how successful the sampling was.

The application form prompted for basic personal information like email address, age, experience level with scrapbooking, and gauging relevancy to the project’s subject matter through a “check all that apply” list of statements such as, “I'm aware that people may perceive me differently depending on what I wear” and “My mood may change depending on what I'm wearing” (see Figure 2).

Participants were selected based on their relation to the statements and scrapbooking/arts-based experience. All applicants adhered to my participant criteria,[1] so I sent out an Availability Form via Google Forms back to them for final selection, which succeeded in narrowing down the ultimate pool of applicants. The last factor in selecting the final participants was considering overall diversity across gender identities from this revised pool. Seven total participants were selected including myself, representing identities such as trans-masculine, cisgender man, non-binary, and genderfluid.

“A work of art is an expressive form created for our perception through sense or imagination and [...] expresses human feeling. [‘F]eeling’ meaning everything that can be felt, from physical sensation [...] to complex emotions, [to] conscious human life.” (168)

– Susanne K. Langer, Expressiveness

[1] In hindsight, it is not that surprising that my queer peers relate to most statements.

Figure 2

Screenshot of Question 11 in the Participant Interest Form.

Scrapbooking Workshop

The scrapbooking workshop was implemented as a way to meet participants face-to-face while sharing knowledge and resources to what was, at the time, an unknown level of creative experience between participants. This workshop was not required to conduct research or collect data, nor mandatory for participants to attend. Beyond providing resources to participants, the workshop also allowed for like-minded individuals to confide in and engage creative with each other. All participants left the workshop fulfilled, wondering when we would all meet again—myself included.

Research Creation Process: Scrapbooking

Following the workshop, a series of documents were shared with participants to help them get started on their scrapbooks. These documents contained a workshop summary inclusive of scrapbooking tips, tools, and techniques; the Scrapbooking Prompt list, consisting of all the questions and reflective prompts generated from personal anecdotes and secondary research during the early stages of the project; and two $10 e-gift cards for participants to acquire any extra materials for the project. The scrapbooking period spanned eleven days, but participants had the freedom to create as few or as many entries as they desired.[2] Although the workshop highlighted analog methods of scrapbooking, participant Kosse pursued digital scrapbooking by combining illustration, handwriting, and photographs on compositions in a digital illustration software called Clip Studio Pro.

[2] I was careful not to foster an environment where it felt like I was running a scrapbook factory.

Reflective Interviews/Debriefs

For research purposes, the interviews and debriefs allowed participants to reflect on the experience of the study from beginning to end and reinterpret their scrapbook entries once complete. Overall, this phase also allowed participants to expand on their contributions in their own voice, with their own interpretations. Participants were given a choice between a virtual interview over Zoom or performing the reflective debrief independently and asynchronously depending on availability and level of comfort. As a participant in this research myself, I chose to conduct an independent debrief, hand-writing responses to my interview questions in my scrapbook and transcribing them digitally. Once all interviews were transcribed and debriefs were received, I proceeded with the coding process.

Each scrapbook entry beamed with nuance, and were therefore difficult to disseminate solely as the researcher through observational methods. Unlike studies like Enclothed Cognition as included in the Literature Review, participants of Dear Diary directly authored their stories. Although this dynamic between researcher and participant is quite common, I believe—in cases where the study is researching human behaviour in relation to their interaction with an object such as clothing—interrogating with embodiment and participants’ perspectives further enhance studies like this.

In the words of gender non-conforming activist and poet Alok Vaid-Menon, “A lot more airtime is given to other peoples’ views of us rather than our own experiences” (14). During this phase of the project, I was reminded again of the significant role dialogue and community play in discourses of queerness.

Data Coding

Transcripts and responses of each participant were reviewed and preliminarily sorted based on relevancy to the main themes of the research. In a deeper analysis of this preliminary collection of data, the most relevant themes to the project were determined and then translated into diagrams to assess the relevance and intersection of certain quotes to the creation/publication of the final zine and my initial literature review (see Figures 3-4).

Figure 3

Screenshot of the author’s process work featuring two colour-coded Venn diagrams. The left diagram identified themes relevant to the creation of the zine, and the right diagram identified themes relevant to the overall research.

Figure 4

Screenshot of the author’s process work featuring all colour-coded thematic categories.

The most populated or otherwise meaningful themes were consolidated into a final series of main themes: Dialogue and Community; Queer Joy; Greater Self-Knowledge; and lastly, Queer Empowerment (see Figure 5). This sequence of themes, generated from a close revision of the coded interview quotes, responded to the inquiry of what scrapbooking can offer as a means of reflecting on the relationship between gender identity and expression through fashion.

Figure 5

Visualization of the author’s consolidated series of themes.

Figure 6

Front cover of Dear Diary, This Is My Gender Today Volume 1.

This zine encompasses the whole research project, its process, scrapbook entries, quotes, findings.[3] Printed versions were given to the participants, kept personally to share during conferences and presentations, and consent was obtained from participants to disseminate digital versions for public viewing, available on my portfolio website.

Queer identities and trans embodiments are often misrepresented, misunderstood, and weaponized for political gain and facilitation of hate. This final zine disrupts these misrepresentations by embodying themes of community, “opening doors to otherness” (Etengoff 217), sharing autobiographical narratives, amplifying perspectives that mainstream media often misconstrues, and sharing knowledge.[4]

“Self-expression sometimes requires other people. Becoming ourselves is a collective journey.” (25)

– Alok Vaid-Menon, Beyond the Gender Binary

[3] It is almost like a yearbook for this project; something for participants and myself to celebrate this process through.

[4] The final zine can be found on the author’s website here: www.miayaguchichow.ca/dear-diary-read-online.

Figure 7

Table of contents and cover spread for Chapter One: About Dear Diary in Dear Diary Volume 1.

Findings

The final themes of Dialogue & Community, Queer Joy, Greater Self-Knowledge, and Queer Empowerment emerged during the coding process from seeking the answer to my research question, “In what ways is scrapbooking an effective method for understanding one’s relationship between gender and fashion?” Dear Diary has proven scrapbooking to be an effective method for bringing community together and creating community in its result; for facilitating queer joy and sharing personal examples of what it is; for developing one’s knowledge of self to a greater degree; and lastly—existing both independently and as a culmination of these three themes —for empowering the queer community. Not only does this section outline each coded finding in depth; it also contextualizes them in their value beyond providing academic insight. Entries and quotes from participants Chloe, Kimber, Kosse, Leo, Liam, Rachel, and myself (Mia) are highlighted here to illuminate these findings and vice versa.

Dialogue & Community

Scrapbooking is known to be a social practice and, when practiced in a group, yields “therapeutic effects”, allowing its participants to cultivate a supportive space in tandem with a creative practice (FioRito 98, 99). A significant number of quotes emerged from interviews and debriefs highlighting the importance of community in the lives of participants, which, to me, gave it value during the coding process in an unprecedented way. One of many concluding points is that a sense of queer community can be found and fostered in both active and passive environments. There were other instances within interview quotes where participants reflected on the effect their communities have had on their ways of dress and self-fashioning, as expressed by participant Kimber (see Figure 8):

[M]y partner's jeans and jean jacket that I just started wearing and have become mine [...] how I feel wearing what was someone else's clothes, the transference of their essence and sense of self, and [how] that shifts, [...] I feel very enmeshed with my partner. [...] It's like being held by those people.

Leo: “We're all kind of like a mosaic of [the] people that we surround ourselves with. [W]hether it's verbiage, slang, interests, music, songs, hobbies, whatever, from the people around us.

Kosse: “Identity is a mirror. We are all mirrors to one another.”

Our identities are not static in time, or representative of one singular thing—sometimes, not even one single person. Sense of community is not restricted to physically existing alongside other individuals; it can also manifest through sentimental memories and attributes woven in the clothing we wear, embedding itself into our embodiment.

Figure 8

One of Kimber’s scrapbook entries reflecting on the pair of jeans and jean jacket mentioned in the above quote.

Figure 9

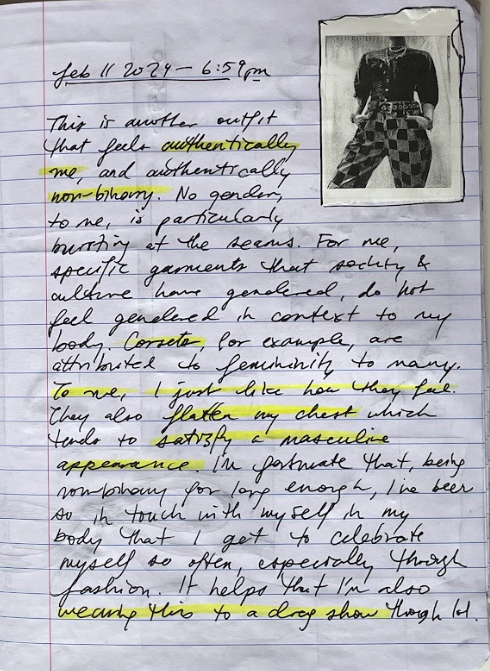

One of Mia’s scrapbook entries from February 11th, 2024, with the last sentence reading, “It helps that I’m also wearing this to a drag show though lol.”

Queer Joy

“[There are] so many queer stories that end in tragedy, and it's just like… let us be happy. Let us get to happily ever after too—share the joy. I'm tired of queer suffering. Bring me queer joy. [...] [The] AIDS epidemic wiped out an entire generation of queer people. [Y]ou kind of really only see younger queer people, and sometimes, you'll see queer people in their forties and fifties, but you aren't really seeing queer people [who are] 60, 70, 80, 90 years old.”

– Leo, Dear Diary participant [interview response]

Seeking ways to let queer joy shine through Dear Diary became an even greater priority after coding for a variety of reasons. It was important that this research and final zine embody true queer joy without erasure of queer-specific struggles. So, what does queer joy look, feel, and sound like in the context of this project? Most examples are found in the final zine, but a couple examples of interest come from participants, Kosse, Liam, and Mia:

Kosse: “I get a certain level of euphoria from being referred to as a man, even though I am not. [...] I had these glasses that I really was enamored with, and the main reason why I haven't worn them was I didn’t want to come across as being like a woman or whatever. But I still like these glasses a lot.”

Figure 10

One of Kosse’s scrapbook entries entitled “4. The Glamour.”

Liam: “Throughout this project, I have been trying to push myself to wear this dress that I own [(see Figure 11)] and I put it on and took it off on about 3 different days throughout this process. [...] I wore the dress to work for the first time and felt visible in a way I have never felt before. I also felt very empowered and beautiful in a way I have never felt before.”

Figure 11

One of Liam’s scrapbook entries from February 9th 2024.

Mia: “In regard to dress, some outfits are more feminine, others more masculine, others beyond. But I, myself, have shed the skin of perceiving my wardrobe through gender. To me, the clothes I choose represent things I love and that’s where I leave it, because it is not their gendered connotations that bring me joy or value.”

Figure 12

One of Mia’s scrapbook entries from February 14th 2024.

The above entries and quotes highlight the peculiar space between euphoria and dysphoria.

Gender is not this rigid contract we sign at birth, binding all aspects of ourselves and our expression to it. Perhaps readers connect with our varying plights in life relating to our identity—gender just happened to play a significant role in it for Dear Diary participants. At the very least, I hope everyone can empathize with our joy. For us, our joy just happens to be queer.

“What I have learned is that creativity lives in the unfamiliar spaces in our minds. We do not make art from following the rules. We make art precisely for imagining beyond them.” (26)

– Alok Vaid-Menon, Beyond the Gender Binary

Greater Self-Knowledge

The third theme is greater self-knowledge within participants, which overlaps with queer joy; however, it is not limited to knowledge within queerness. In conclusion to their time scrapbooking, participants Chloe and Kosse described their experience in the following interview and debrief responses:

Chloe: “Reflecting on all of these things, I just learned more about myself through the process.”

Kosse: “A lot of it came down to being a reaffirmation of things that I knew I wanted, but I didn't fully recognize how badly I might have needed them until I did this project. [...]

[I have] a freedom that I never had before, and [I am now] able to move confidently into the future with that knowledge.”

Although this experience of gaining clarity on what already exists is not exclusive to queerness, it oftentimes is a prerequisite. Everybody’s gender journey exists at different points in their timelines, not to mention our greater collective timeline. Community is powerful; queer joy is powerful; knowledge is powerful. This realization is what brought me to the culmination of all these themes, which is queer empowerment.

Queer Empowerment

We cannot truly understand how we dress without asking why we dress. This project also encourages a more conscious culture for both the individual and others around us—not only for making conscious choices to achieve higher queer joy in our clothes, but for others perceiving us to respect what lies beyond the surface. We must all be aware of the complexity beyond a single visual cue. We tell our story by fashioning ourselves.

Every participant employed both written reflections and multi-media approaches. Even within the lack of pressure to integrate illustrative media in their entries, all participants included illustrations of varying degrees in one or more entries (see Figures 13-19).

Figure 13

One of Liam’s scrapbook entries..

Figure 14

One of Kosse’s digital scrapbook entries entitled “2. The Silhouette.”.

Figure 15

One of Rachel’s scrapbook entries.

Figure 16

One of Leo’s scrapbook entries.

Figure 17

One of Kimber’s scrapbook entries.

Figure 18

One of Chloe’s scrapbook entries.

Figure 19

One of Mia’s scrapbook entries.

In relation to the experience of Dear Diary, participants Liam and Rachel shared:

Liam: “When I couldn’t find the words to express what I wanted to, I was able to draw or even just scribble until I ended up with a shape or an outfit. [...] I feel like reflecting on these outfits changed the way I felt about myself even in the moment. I think I was able to see a lot of beauty on the page after I had finished reflecting, some beauty that I wasn’t able to see in real life when I looked in the mirror.”

Rachel: “The collaging was really fun to just physically map out, and it was almost like another form of ‘how do I express this outfit through the way I put these images together.’ There was a cool additional layer of expression through that.”

Queer and trans people fight to be understood every day within systems that oppress and misunderstand them. We are tired of fighting. When do we get to experience our joy without direct relation to struggle? Dear Diary strived to offer that to its participants— freely scrapbooking, tunneling in on the parts of ourselves that bring us joy, celebrating it across each page, and sharing that with its readers.

Conclusion

Figure 20

Introductory spread to Chapter Three: Conclusion in Dear Diary Volume 1.

This research has given gender-variant folks a multi-faceted artistic platform to explore and express their identities in a fulfilling way. It also contributes to the ever-evolving discourse of gender identity and expression, expands on embodiment in fashion, and is an example of research employing languages beyond just the written word. Within the intersections of art and academics, I see great value in presenting research in nuanced forms and I invite readers to generate their own conclusions from the data presented—to, in a way, invite them into the research as well. Dear Diary did not come without its challenges or barriers, but overall, it has the potential to continue in its current form to impact more gender-variant individuals, or morph into something else completely different in an ever-evolving society.

Contributions

In dialogue with its literary inspirations, this paper expands on how the ongoing project of Dear Diary challenges and expands on research done by authors such as Sophie Woodward (2007) on topics like gender, identity, self-expression, and the wardrobe by recontextualizing her in-depth research through a queer lens. Being non-binary and researching gender variance does not make me an expert on non-binary identities by default; we are all uniquely and individually complex, therefore, inviting other perspectives is key to optimizing results. In fact, the findings of Dear Diary are entirely born from participants’ responses. Dear Diary has proven that research can have benefits outside of academia, need not rely on the written or spoken word for adequate results, can both amplify underrepresented voices while collecting valuable data, and that art is a sufficient research method for nuanced topics.

Limitations

Future manifestations of Dear Diary would benefit from a more diverse participant pool in age, geographical location or cultural background, ability and disability. Specifically, all participants were within similar age ranges to each other, and there were no individuals identifying as trans women or trans-femme. Furthermore, due to factors such as the workshop being in-person, recruitment was also only limited to applicants within Toronto. In the future, I would be interested in exploring options for digital scrapbooking for broader accessibility—both to accommodate varying disabilities and expand the project’s geographical diversity and reach. Although age was not a participant criterion other than simply needing to be over 19 years of age for consent purposes, there is a unique opportunity to explore how younger individuals such as teenagers would interact with this study. As a result of some setbacks in the early stages of the research, the execution of the overall project was condensed into four months instead of an initial plan of nine and plans for expanded zine-related research were cut out. In addition to the main scrapbooking component, additional methods may be added, such as surveys or questionnaires, to not only triangulate my approach but also allow for different levels of participation and anonymity for participants who do not have the capacity for the full breadth of the project but still want to contribute.

The Future of Dear Diary

Given the proven longevity of scrapbooking as a practice and its overall benefits both in and out of the queer community, I would like Dear Diary to continue as a community arts initiative supported by research, rather than a continued academic study. The long-term goal for Dear Diary is to expand it to the greater queer community both in Toronto and beyond. I imagine Dear Diary continuing to operate at a local level through in-person workshops and get-togethers, sharing resources through zines, and more. There is also room for Dear Diary to live online across geographical borders, allowing users to submit or create scrapbook entries based on the original project prompts, generating an online archive and community. Additionally, I imagine Dear Diary manifesting in an in-person exhibition, featuring parts of entries from future participants and allowing for interactivity among guests, activations or events around queer fashion and identity, and more. As an extension to local initiatives, I hope to publish and distribute a Do-It-Yourself volume of Dear Diary to share the research materials with the public and potentially publish a volume just of my own scrapbook entries while encouraging other participants to do the same and share their stories. Dear Diary could be employed as a one-off goal-oriented therapeutic process or as an ongoing artistic and reflective practice. I do not see Dear Diary as this monumental thing that will solve all gender discourse issues; it simply demonstrates another available language for gender-diverse people to speak with that has the potential to appeal to others in a way that words cannot.

Dear Diary Today

Participants have received their zines. I have presented my research to my peers and at the Unravelling Fashion Narratives symposium in June 2024, shared the digital zine online,[5] have begun inviting Dear Diary Volume 1 participants to a community Discord server, and have completed my own scrapbook. Upon catching up with participants, they mostly did not continue the practices of Dear Diary, but some still scrapbook casually. Practicing Dear Diary reminds me of the little things that bring me joy, like matching my makeup to my shirt colour, or putting on my favourite pink watch. These little things amount to the reaffirmation of my gender variance. Memories fade, but transness is forever. And it is this that is the most important part of my entries—not the way they look, or the way I look.

[5] Read Dear Diary Volume 1 online at https://miayaguchichow.ca/dear-diary-volume-1-digital-pdf.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Ben Barry for the incredible support as my MRP supervisor, Joseph Medaglia as my second reader, participants Chloe, Kimber, Kosse, Leo, Liam, and Rachel for their generous contributions to Dear Diary, and everybody who has shown support for this project throughout its conception and upon its publication. An additional thank you to the Student Editorial Board of Fashion Studies Special Issue: Unravelling Fashion Narratives for taking the time to review my paper.

Works Cited

The Trans Legislation Tracker. 2024 Anti-Trans Bills: Trans Legislation Tracker.

Adam, Hajo, and Adam D. Galinsky. “Enclothed Cognition.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 48, no. 4, 2012, 918-925. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/ pii/S0022103112000200?via%3Dihub.

Armstrong, Lyndsay, and Sarah Smellie. “LGBTQ2S+ Activists Fearful of a Poilievre Government, Some Say Trudeau Should Step Down.” CTV News, 4 September 2024, www.ctvnews.ca/mobile/politics/lgbtq2s-activists-fearful-of-a-poilievre-government-some-say-trudeau-should-step-down-1.7024555?clipId=263414.

Barry, Ben. “Enclothed Knowledge: The Fashion Show as a Method of Dissemination in Arts-Informed Research.” Fashion Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018, 1-43, https://doi. org/10.38055/FS010104.

Camus, Albert. Create Dangerously: The Power and Responsibility of the Artist. 2019. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Catalpa, Jory M., and Jenifer K. McGuire. “Mirror Epiphany: Transpersons’ Use of Dress to Create and Sustain Their Affirmed Gender Identites.” Crossing Gender Boundaries: Fashion to Create, Disrupt, and Transcend, 2020, pp. 47-59. Intellect Books Ltd.

DeBauche, Leslie M. “Breaching Flowery Borders: Early Twentieth Century Girls Scrapbooking Their Lives.” Girlhood Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 2021, 124–39.

Etengoff, Chana. "Using Zines to Teach about Gender Minority Experiences and Mixed- Methods Research." Feminist Teacher, vol. 25 no. 2, 2016, 211-218. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/article/619256.

FioRito, Taylor A., et al. “Creative Nostalgia: Social and Psychological Benefits of Scrapbooking.” Art Therapy, vol. 38, no. 2, 2021, 98–103.

Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability. 2018. University of California Press.

Hesselbein, Chris. “Walking the Catwalk: From Dressed Body to Dressed Embodiment.” Fashion Theory, vol. 25, no. 3, 367-393, DOI: 10.1080/1362704X.2019.1634412.

Langer, Susanne K. “Expressiveness.” Problems of Art 1957, 13-27. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lovata, Troy R. “Zines: Individual to Community.” Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues. 2008, 2-12. Thousand Oaks, CA, SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226545.

Sampson, Ellen. “Wearing and Being Worn.” Worn: Footwear, Attachment and the Affects of Wear, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2020, 72-95.

Taylor, Brooke. “'Rights Aren't a Competition': Anti-Trans Hate is on the Rise in Canada, Activists and Advocates say.” CTV News, 31 July 2021. www.ctvnews.ca/canada/ rights-aren-t-a-competition-anti-trans-hate-is-on-the-rise-in-canada-activists-and-advocates-say-1.5530155.

Vaid-Menon, Alok. Beyond The Gender Binary. 2020. Penguin Young Readers.

Walling-Wefelmeyer, Ros. “The Methodological Potential of Scrapbooking: Theory, Application, and Evaluation.” Sociological Research Online, vol. 26, no. 1, 3-26. DOI: 10.1177/1360780420909128.

Wilson, Brock. “Misinformation Persists Online after Super-Brief Olympic Boxing Bout.” CBC News, 3 August 2024. www.cbc.ca/news/world/imane-khelif-algerian-boxer-gender-1.7283949.

Woodward, Sophie. Why Women Wear What They Wear. 2007. Berg Publishers.

Author Bio

Mia Yaguchi-Chow (they/them) is a multidisciplinary artist born and raised in Toronto, Ontario. After receiving their Bachelor of Design in Fashion (2021) and their Master of Arts in Fashion (2024) at Toronto Metropolitan University, they are currently working in the field, specializing in graphic design, photography, illustration, visual storytelling, and more. Mia seeks to disrupt and subvert conventions in academia and research with “alternative” research methods, radical thinking, community-centred pursuits, and unapologetic expression. Outside of academia, Mia spends their time on personal creative projects and experimenting with their practice, seeking ways to share knowledge and create opportunities for their community. You can find more of Mia's work on their website at www.miayaguchichow. ca and on YouTube at www.youtube.com/bitchfitsproductions.

Article Citation

Yaguchi-Chow, Mia. “Dear Diary, This is my Gender Today.” Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-28. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050102

Copyright © 2025 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)