Dressed in Time: In Conversation with Dr. Margaret Maynard

& Dr. Elizabeth Kutesko

abstract

We know that time is central to our understanding of dress and clothing, encompassing questions of speed, slowness, production and consumption, and representation. Yet time and clocks are not neutral, but rather serve political, economic, technological, and imperial purposes in their everyday shaping of bodies and fashion. Who sets the dominant pace of fashion, after all, and how does this manifest in the surrounding visual and material cultures of dress, as well as how we research and write about them?

This conversation between Elizabeth Kutesko and Margaret Maynard arose from Elizabeth’s fascination surrounding the recently published book Dressed in Time: A World View (2022), and Maynard’s use of time as an interrogative tool to foreground the complexity of global dress practices that extend far beyond historians’ favouring of linear chronology and periodization. This conversation also responds to the current turn within the humanities—namely anthropology, history, material culture and museum studies, and design history—whereby time has become of central concern.

Volume 4, Issue 2, Article 4

Keywords

Time

Global Dress

Global

Perspectives

Decentering

Fashion

Global Histories

DOI: 10.38055/FS040204

MLA: Kutesko, Elizabeth. “Dressed in Time: In Conversation with Dr. Margaret Maynard & Dr. Elizabeth Kutesko” Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2023, pp. 1-21, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040204.

APA: Kutesko, E. (2023) Dressed in Time: In Conversation with Dr. Margaret Maynard & Dr. Elizabeth Kutesko. Fashion Studies, 4(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040204.

Chicago: Kutesko, Elizabeth. “Dressed in Time: In Conversation with Dr. Margaret Maynard & Dr. Elizabeth Kutesko.” Fashion Studies 4, no. 2 (2023): 1-21. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040204.

Figure 1

Elizabeth’s copy of Dressed in Time: A World View, London, August 2023.

Elizabeth

In the preface to Dressed in Time: A World View (2022), you say that you have always felt there was more to dress history than Western Europe. This really resonated with my interest in exploring fashion as a transnational phenomenon, yet one that is repeatedly used to serve national agendas and often capitalizes on pervasive stereotypes to create cultural value. Indeed, your earlier book Dress and Globalisation (2004) underlined the power and complexities of dress and fashion from a global perspective. I’m interested in what led to you to use time as the fundamental scaffolding for this book, and as a tool to interrogate your longstanding interest in global dress and fashion practices further still? Why “time,” in other words, as opposed to “space,” since the latter clearly also resonates with your interest in how global exchange intersects with material culture?

Margaret

This is a very relevant question. Susan Kaiser’s important book Fashion and Cultural Studies (2012) proposed a model of fashion as circuitous, intertwining time and space beyond binaries. Its “routes,” she suggested, are not linear but entangled and navigate space beyond major fashion centres—these routes intertwine with the past and the present. I accepted this argument but also sought to reconsider time in particular as the best way to challenge both conventional dress and fashion methodologies. I wanted to consider through discontinuities and the atypical that time lies at the centre of all clothing concerns.

Fashioning the body from concept to actuality cannot be claimed to originate in accepted Western and Asian fashion centres. Beyond this, I wanted to leave room for wider considerations of clothing, for instance to examine examples like the mysterious and quite curious Tarkhan “dress,” or what constitutes rarity and value in some garments but not others—questioning what we consider as the past and how it changes the nature of cultural memories.

Figure 2

Tarkhan Dress, c. 3482-3182 BCE, Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London.

Elizabeth

Yes, and in many ways the Tarkhan dress is exceptional to many viewers simply because of its age, since it taps into a broader desire to locate tangible traces of the past in the “oldest surviving” examples of dress and accessories. I’m thinking of the allegedly earliest known leather shoe, this is the one illustrated in your book, which I recently stumbled across in the History Museum of Armenia in Yerevan. It was found in the Areni-1 cave in Vayots Dzor province but, as you underline in Dressed in Time, such statements need to be carefully assessed since the “‘oldest’” can probably never remain so” (2022, p. 42).

How then does the lens of time enable us to use such mysterious items to address the current limitations and Eurocentric biases of dress history and fashion studies to date in a revised way, and to challenge many of the pervasive assumptions about what is deemed fashionable and what is not? Adding to that, do you see any limitations to using “time” as the unifying link for examining dress and fashion practices in global perspective?

Margaret

There is no doubt that Western clock time transposed to colonial environments was a key factor in shaping social hierarchies. Different cultures, different localities, and different constituencies have obviously had their own understandings of time. So, time is not so much limited or a unifying link to examine dress, rather a relative and mutable experience that provides new methods of exploring all forms of clothing, enabling us to assess meaning that may differ across most social differences. Lemire et al. in their study of global material culture, Object Lives and Global Histories in Northern North America: Material Culture in Motion (2021), use the term “more capacious chronologies” to usefully revise understandings of trade entanglements across nations, in particular across the Atlantic.

There is a grain of truth in the term “period style,” but I hoped in my book to show that clothes as worn, depicted, exchanged, unused, and stored away are often infinitely fragile in their meanings.

The Western organization of time has had a major impact on the dress habits of colonial occupiers, and material and social distance played a complex part in shaping their urban and rural attire (see my short essay “Distance and Respectability” in The Fashion History Reader (2010). The imposition of Western time also profoundly affected subject peoples with their own understandings of it. This certainly caused serious misunderstandings of clothing and the etiquette of dress resulting in problematic working relationships, interpersonal friction, and even eventuated in major health problems. But there are plenty of examples of more positive cross-cultural appropriation of garments and motifs.

elizabeth

Absolutely. The complexity and mutability of time in different social and cultural contexts reminds us of the multiplicity of knowledges, yet at the same time Western-centric clock time has been imposed upon bodies and used to regulate and discipline them.

Going back to your training, how have your early interests and background led you to your current research interests? What about the training that you had at the Courtauld under Stella Mary Newton; did this have an impact upon your thinking? You seemed to suggest in our earlier conversation that the Courtauld helped you to think in a certain way, even if your research interests always lay beyond the remit of dress in Western Europe.

Figure 3

Aboriginal woman wearing a possum skin cloak, ca. 1870. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

margaret

I have had the privilege of living in Africa, Papua New Guinea, and in Australia. This has broadened my perspective on the nature of body coverings immensely. My years of study at the Courtauld Institute were a profound influence, but I came to believe that looking at European art and surviving dress was inspirational but also limiting… I have always felt that the clothing of the under classes needs to be a major aspect of any study of dress. For this reason, the complexities of the clothing of transported convicts to Australia formed an important part of my book Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia (1994). I continue to be fascinated by the dress of the so-called “lower-or working-classes.” At the same time, I believe in the power of intense looking and the nature of creativity present in so much dress expresses the individuality of all peoples. But I feel strongly that confining research to the Western Hemisphere restricts scholars from understanding the powers of time as exemplified in cultural contacts. Hence my delight to be able to contribute to the Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands volume of the Berg Encyclopedia of Dress and Fashion (2010) edited by Joanne B. Eicher.

elizabeth

In the book you write that “time lies at the centre of all clothing concerns, not just those of high-end dress. Every garment has its own pace” (2022, p. 2). I really like this notion that every garment has its own pace and narrative, namely because it reminds us that both materials and material objects acquire meaning as they move around the world, crossing borders and passing through different pairs of hands. Can you say a bit more about this please? And how we might go about tracking the pace and narrative of individual garments — especially if we know nothing of their wearers?margaret

This is a very valid question and there is no straightforward answer.

Tracking this if we don’t know the wearers, as in a representation, must rely on a prior or general knowledge of the garments depicted and experience of wide “looking.” Certainly, a photograph or fashion drawing adds a significant element to the study of garments as there are temporal and social gaps between wearers and their observers, plus the effect of the nature of the image-making method itself. All this complicates dealing with unknown wearers and their clothing. In short, I accept that the term “documentary” needs to be qualified in respect of images.

Elizabeth

Indeed, Patricia Aufderheide in Documentary Film: A Very Short Introduction (2007) writes that “documentaries are about real life. They are not real life. They are not even windows onto real life” (p. 2). I’m asking the question because I’ve been thinking about how I might use your notion of the “individual pace of a garment” within my current research. I’m looking predominantly at the representation of dress in visual culture, rather than material objects. But I’m interested in how certain items of dress can act as protagonists within photographic representation, namely by disrupting our understanding of chronos, linear, chronological, quantitative time, and offering glimpses of kairos, a more spontaneous and qualitative time. For example, in a photograph taken in 1911 by American photographer Dana B. Merrill (Figure 4), two anonymous workers of the Global Majority are documented in the Brazilian Amazon where they have been helping to construct the Madeira-Mamoré railroad. Built between 1907 and 1912, the Madeira-Mamoré railroad carved a line through impenetrable rainforest from Porto Velho, a shipping point on the eastern bank of the Madeira River in the Brazilian state of Rôndonia, to Guajará-Mirim, situated on the Mamoré river on the Bolivian-Brazilian border. Intended to expedite the global exportation of rubber and other tropical commodities from landlocked Bolivia, it provided an outlet through the upper-Amazon basin in Brazil to the Atlantic Ocean and onto the markets of Europe and North America.

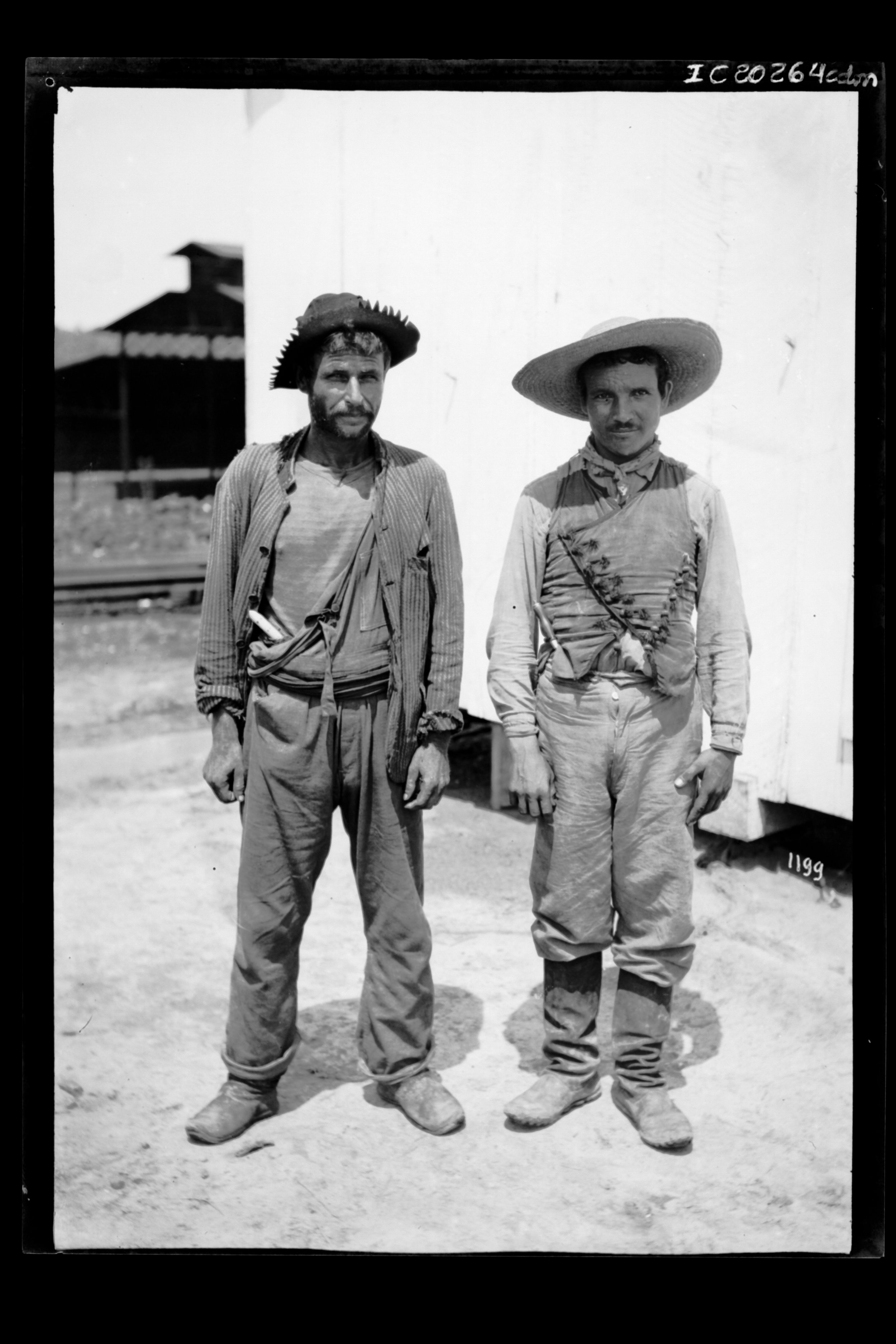

Figure 4

Dana B. Merrill, Two anonymous workers on the Madeira-Mamoré railroad, 1910-11. Dana Merrill Collection, Museu Paulista.

The workers on the railroad were organized according to a strict time regime, which is unsurprising given that the photograph was taken the same year that Frederick Winslow Taylor advocated efficiency in his instructive manual The Principles of Scientific Management (1911), stating that there was a need to stop employees “soldiering.” He sought to counteract laziness and slowness by allocating a specific scientific time to each task. I was intrigued by how Merrill, the official photographer employed on the railroad, had documented these workers in such a measured and deliberate way, using a large-format camera that slows down the image-making process and asks that the subjects stand poised for a prolonged period of time. Their worn clothing — such as the waistcoat sported by the man on the right — is a literal embodiment of time having passed, containing the lived experiences of their wearers, which resonates with the photographer’s considered approach to documentation that seems to demand from the viewer an equally slow and measured mode of viewing.

My research traced this waistcoat to Greece, because of its distinctive cut that has a clear Balkan influence (Figure 5). Yet, here it is worn in the Amazon as everyday working dress, possibly to serve as a synecdoche for home. To complicate things further, we know that when employees died on the railroad, their clothing was often sold to other workers — so this could even be quite a “new” garment for the wearer, despite its aging material qualities, who may not even originate from southeastern Europe. In other words, there are so many different temporalities contained within this one item. Your discussion of measuring the pace of a garment from its production to consumption to post-consumption afterlife really resonated for me, because it helped me to untangle the nuances and complexities of the dress cultures that build up around transnational construction projects such as the Madeira-Mamoré railroad and which tap into the temporal rhythms of everyday life.

Figure 5

Cretan waistcoat, made for Marietta Pallis in London by tailor Emmanuel Baladinos, of Chania, Crete in 1930. Benaki Museum, Athens.

FIgure 5b

Shawl Fragment, India. Ca. 1800. Gift of Lea S. Luquer. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Elizabeth

Moving on from current research interests, given the recent and broader scholarly interest in time, how do you place the book alongside other contributions to fashion and temporality which have come to the surface recently, such as Evans’ and Vaccari’s anthology Time in Fashion: Industrial, Antilinear and Uchronic Temporalities (2020) or the Met exhibition About Time: Fashion and Duration (2020-21)? How do you see your perspective and the attention that you place on fashion and dress as different from or aligned with these contributions? Both of the above seem to show a more complicated relationship that fashion has to time, which moves beyond linear chronology, periodization and context to show us new alternatives, but they are also both predominantly concerned with Western-centric perspectives.

Margaret

I would agree about the newness of approach in these two recent contributions, although as you say both were predominantly Western in focus. Both certainly provided rather different concepts of fashion and time than previously. It was very pleasing to see.

The Met’s exhibition About Time (2020–2021) was a lavish exploration of a timeline of couture garments unfolding along two galleries set up as giant clockfaces, one stressing linear progress and the other that spoke to the first, disrupting chronological time in an attempt to represent the philosophical ideas of Henri Bergson. Whilst it was an important attempt to engage materially and theoretically with fashion and time, it centred on high-end couture garments. Rather disappointingly, it reproduced some stereotypes about fashion, including the clockface structure and the focus on black garments (common in silhouette timelines), all themes I question in my book. It is the Met’s brief to show their finest garments, but my approach to dress and time is more socially inclusive.

The publication Time in Fashion (2020) by Evans and Vaccari, both highly regarded authors in the field, is a fascinating theoretical anthology offering a clear way through complex interdisciplinary ideas from a wide range of sources: fashion magazines, news clippings, fashion writings, and designers. Structured around three ways to consider time in relation to fashion, this is an impressive achievement. The topic is clearly one that is gathering interest, but my deep fascination with material objects is the reason I find this publication rather limited by its theoretical structure.

Elizabeth

You’ve said before that your great regret is not having studied anthropology, which I fully empathize with. What do you think anthropology as a discipline most has to offer in terms of helping us to understand the transnational production and consumption of fashion in global frameworks?

Margaret

Anthropology has always accepted both fashion and dress/clothing of all kinds as potential research subjects. Its wide parameters and social import is, for me, its major interest. It is the inclusivity of the work of anthropologists and ethnographers that draws me to their work. Luvaas and Eicher (2019) say that anthropologists originally tended to be interested in the topics of fashion and dress of all classes and periods but not as subjects in their own right. This has changed, but there is still no such thing as the Anthropology of Dress and Fashion. My own attraction to anthropology is the willingness to redefine fashion by moving widely beyond Western western, European, and other major urban centres, and to embrace different forms of social hierarchies and practices in all forms of body covering, modification and adornment.

Elizabeth

Yes, and that leads me on to something that concerns me about anthropology, which is the problematic relation that it has to time. I’m talking largely in terms of how as a discipline it has drawn delineations historically between those cultures that were seen in temporal terms as fast, fluid, accelerating, and progressive, and those understood to be slow, static, fixed, or timeless. Fabian, whose work you cite on a few occasions, wrote about how anthropology denies co-evalness to its subject (non-Western western cultures). In other words, how do we navigate the opportunities that anthropology provides for studying fashion at a global perspective, with the ways that it has historically shaped and served dominant and racist ideologies with reference to time, by organizing social, cultural, ethnic, and racial bodies in terms of their perceived changeability or fixity? This is something that I’m grappling with in my research too.

Margaret

This is a very pertinent question. Anthropology is not a static discipline and Fabian was writing some time ago. I think that any idea global fashion/dress serves the dominant culture in terms of fluidity and the progressive, and that the dress of ethnic and non-Western cultures are static has now been well challenged.

I find your images of two workers (Figure 4) very fascinating. The two men depicted in your photograph, passively reversing their normal working activities, are, in their individuality, also the opposite of scientific factory Taylorism. The clothing of each man is so markedly different in every way suggesting individual temporal narratives. Their stances are almost deliberately anti-heroic. Could you call this ethnographic photography?

figure 7

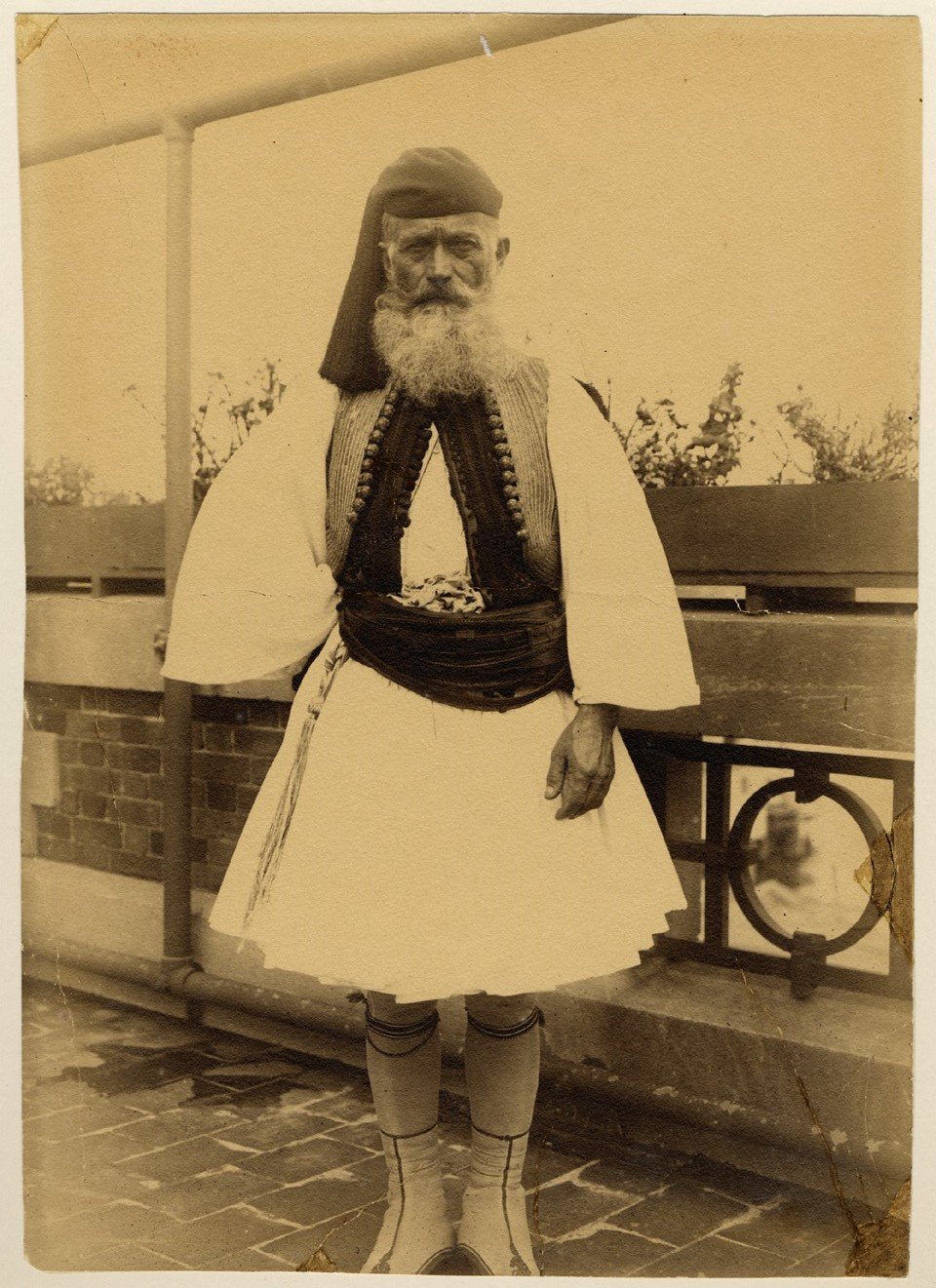

Augustus Sherman, A Greek Soldier, Ellis Island, 1911. New York Public Library.

Figure 8

Dana B. Merrill, Barbadian workers in the Steam Laundry on the Madeira-Mamoré railroad, 1910-11. Dana Merrill Collection, Museu Paulista.

elizabeth

I actually refer to these photographs (Figure 4) as portraits, because of the attention paid to the individual characteristics of the subjects. But I agree that there is this tension with ethnographic photography, this desire for taxonomy that chimes with the work of August Sander’s social documentary of different “types” as well as Augustus Sherman’s photographs of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, New York (Figure 7). I use photographs to look very closely at dress practices and time during a charged period in history that drew many migrants together around a transnational industrial project, during the peak of North American capitalist expansion and exploitation of the Amazon in the early-twentieth century. There were a few women who worked on the railroad too, such as the Barbadian women who worked in the Steam Laundry (Figure 8), helping to wash the workers’ clothes in the interests of health and hygiene, but the photographer’s gaze was rarely trained upon them.

Your book draws upon so many fascinating examples of time and dress from such a broad span. I’m interested to know how you selected them, and for how long have you been researching the content that went into it?

Figure 9a & 9b

Replica woman’s jacket 1615-18 embroidered in 2018-19. National Trust for Scotland, Culross Palace and Gardens. The embroidery by the Culcross Needlework Group (coordinated by June McAleece).

Margaret

Before I answer your question, it occurs to me that relational attention to juxtaposing “types” and my views of dress as subject to multifarious hierarchies—its elements moving though time—might be something useful to consider.

Back to the main question, I took five years to write this book and drew on many lifetime interests for topics. The very first outing Stella Newton asked our class to take was to see the ancient Order of the Garter Ceremony at Windsor. She had lectured on the medieval origins of the Order and wanted us to see the robes which have remained markedly similar over the years, such as the curious vestigial male chaperon (headwear) still worn by all members on their right shoulders. When I discovered the dress of the coronation of the King and Queen of Tonga in 2015 was based on Queen Elizabeth II’s Coronation attire, I was keen to do a chapter on ritual and the temporal—to consider how some ritual dress lasts stylistically over time but other official clothing far less so.

In a number of cases I chose to research dress I found particularly intriguing, even mysterious. These had nothing to do with historic dress in Britain but were colonial examples. Several were taken from clothes in Australian collections like the Sydney, Hyde Park convict shirt, and Mrs. Marsden’s curious day dress. I intended to include cloaks of various kinds which are universal garments of dignity but with practical origins. Aboriginal cloaks are particularly interesting but also symbolic body coverings. They have now been co-opted as potent political emblems of Indigenous cultures.

Some of this has to do with historic links to the owners, but memory and the local concept of heritage lies at the core of many examples. So, some of my topics drew on this interest in relative value.

Elizabeth

One thing that resonated when we last spoke is you querying how one can date, for example, a photograph so simplistically as being from the 1950s, when the subject may be wearing shoes from the 1920s. Our wardrobes and outfits are, as you outline, comprised of varied temporalities, of things acquired during different times or passed down. I’m also wondering if we need different research methods in order to track the pace of fashion items in which change may appear to operate quite slowly. What might those methods look like?

margaret

I have been thinking about this recently, especially in relation to Western styles of the 1920s and 1960s. On one level I think that I am incorrect to say there is no period style, but my knowledge of the culture and economy of these periods reassures me that there are at least two levels of interpretation for these periods. I sense that there is no clear answer to your question other than to be mindful that ideal dress in fashion photography or other advertisements, even family photos, can project the essence of a particular period—whether it is the dress, the poses, the expressions, and the hair arrangements, or indeed as a whole. At the same time, close-looking and wider research and contemporary commentary often reveals that there is not always such a convenient period generalization. Dating of imagery is complicated by the nature of the photographer or sketcher’s intentions and in fashion photography the emphasis on images to promote consumption. I think there are forms of pictorial convention that can operate on another level from the everyday material nature of wearing.

elizabeth

Exactly. Representation adds an additional layer of meaning to dress. You write that “time and dress merge in the acts of making, remaking, trading, ‘handing down’, and more” (2022, p. xv). Do you understand the ways that dress has merged with time as markedly different from how fashion has? In other words, is fashion simply “change in dress,” as Joanne Eicher seems to imply, or is it an altogether different beast with its own temporal logic? How are we defining the differences between fashion and dress?

margaret

There have been numerous attempts to explain fashion/dress as a way of defining ourselves and communicating with others. Eicher and Roach-Higgins’ (1992) definition of dress as an assemblage of body modifications and body supplementations is well known. Luvaas and Eicher (2019) suggest that fashion can be explained as a wider process of systematic change with profit in mind. On the other hand, I feel that the differences between fashion and dress are far more nuanced. I understand fashion to be high-end style and quality which is sufficiently aesthetically interesting and different from the immediate past to attract imitation or purchases by consumers of means. It has its own specific itineraries from conception to wear. Yet, fashions can also be personal adjustments to body covering that are more everyday styles whose inventiveness itself encourages others to do the same. I suggest that the temporal logic of dress differs from that of high fashion. The reason is that haute couture in particular is shaped ideally as one coherent statement. Dress, on the other hand, can be made up of a multiple of entities drawn from many sources. Yet fast fashion, something that has a very short life span, is like dress and may be used with different accessories not conceived as a whole. It is complicated.

elizabeth

Yes, it is complicated. Something that Eicher wrote and which really resonated for me, although I am still “testing” it, is that “fashion is, after all, about change and change happens in every culture because human beings are creative and flexible” (2001, p. 11). She seems to suggest that fashion can be everywhere, although it leads me to question what methods we might use to study change that happens at a very slow pace. In proposing to take a global view with the book, you predominantly use time in its Western understanding. Is this conscious? Is it to do with how fundamental time was as a tool of colonization that becomes so apparent in delineating different dress cultures, as Giordano Nanni articles in his book The Colonisation of Time (2012)? Or has it been difficult to locate written sources concerning non-Western uses of time? And I ask this, once again, because it’s something else that I am grappling with in my current research.

Figure 10

Lady with a portrait of Jahangir, ca. 1603, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of John Gellatly.

margaret

I have taken a Western understanding of time perhaps through necessity. Even so, I believe there to be multiple registers of time according to culture and historical period. I was very impressed with Nanni’s account of the effect of Imperial time on subject peoples and would have liked to have found further work of this kind. I was not able to access many publications specifically on non-Western time although there are many essays in the Berg Encyclopedia of Dress and Fashion edited by Joanne B. Eicher that have excellent examples of a diversity of temporal differences around the world, some written by anthropologists and some by ethnologists.

elizabeth

I also find Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion to be an incredible resource. Of all the readings that you must have done on time for the research of the current book, which resonated the most?

margaret

The following authors (in no particular order) were ones that impressed me greatly and opened my mind to new ideas. There were of course a great many more.

Penelope Corfield’s many works on time that focus on discontinuities of the temporal rather than linear periods was of considerable use to me in understanding the different kinds of time.

Ariadne Fennetaux et al., The Afterlife of Used Things, (2015).

David Shankland ed., Archaeology and Anthropology. Past, Present and Future, (2012).

Karen de Perthuis, “Darning Mark’s Jumper. Wearing Love and Sorrow,” Cultural Studies Review, 22: 1 (2016) is a moving account of memory and loss which I feel to be essential reading.

Giordano Nanni, The Colonisation of Time: Ritual, Routine and Resistance in the British Empire, (2013) was an inspiration.

Ian Gilligan, Climate, Clothing and Agriculture in Prehistory: Linking Evidence, Causes and Effects, (2018).

Beverley Lemire et al., Object lives and Global Histories in Northern North America. Material Culture in Motion, (2021). I discovered this book at the end of my research and was fascinated by the interest in what Lemire calls ‘atypical time.’

Ellen Sampson, The Shoe as Palimpsest Imprint: Imprint, Memory and Non-contemporaneity in Worn Objects, (2013).

elizabeth

In presenting new approaches to dress history and fashion studies, how can we interrogate the relationship of time to history further? For example, I’ve taught a new course to my MAs titled Re-imagining Fashion Histories: Tracing Parallel Cosmologies where we begin by exploding understandings of history as linear chronology, a totalizing narrative of ‘progress’ that places Western Europe and North America at its core. Having ‘exploded’ history as a discipline, we then use lectures and workshops to spotlight unheard voices from fashion’s histories, illuminating the transnational networks of exchange and influence that underpin an evolving fashion system predicated on the exploitation of people, resources, and the environment. The idea is to underline how the past, rather like fashion, is altogether more contentious, convoluted and confusing than coffee table tomes and library shelves privileging elite designers suggest. The aim is to encourage our students to interrogate the verb “imagine” as one that can refer to both colonial modernity (Orientalism was, after all, a process of imagining) but that can also align with the decolonial move in terms of imagining alternative worlds. We draw here on Saidiya Hartman’s notion of ‘critical fabulation. But sometimes a few of my students find it hard to see a structure in what we are doing. I think they are so ingrained with an individualistic approach of the ‘ego’ to fashion, which fashion schools perpetuate when they place famous alumni on a pedestal, rather than a relational one.

margaret

I feel that one cannot fully do away with linear historical accounts of dress and fashion. Elite fashion needs to be studied in order to make sense of everything else. Once a broad overview is covered, it seems to me that its limitations will show up and it would be useful comparative material. At the same time, it is a limiting method of study. Once this structure is broadly in place, it would be possible to bring in your contentious examples and problematic issues. I don’t think it is necessary to do away with either method. The new Cambridge Global History of Fashion (2023) might be very useful to check. I have not read it, but it would seem to be an important redress to the current emphasis on Western fashion.

Author Bios

Elizabeth Kutesko is a cultural historian and alumna of the Courtauld Institute of Art, where she obtained her PhD in 2016. She leads the BA in Fashion Histories & Theories and the MA in Fashion Histories & Theories at Central Saint Martins. She is the author of Fashioning Brazil: Globalization and the Representation of Brazilian Dress in National Geographic (2018) and is currently working on a new monograph that brings to the fore the unknown global workforce who constructed the 366 kilometer (224 miles) Madeira-Mamoré railroad, built deep in the Brazilian Amazon between 1907 and 1912, through the lens of everyday dress, photography, timekeeping and imperialism. Further information on her projects can be viewed at elizabethkutesko.com.

Margaret Maynard is Associate Professor and Honorary Research Consultant in the School of Communication and Arts at the University of Queensland, Australia. She is a dress and art historian and the author of a number of books, chapters and articles on fashion, dress and photography as well as articles on colonial art history. Books include Fashioned from Penury: Dress and Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia (1994), the first academic text on Australian dress, Out of Line: Australian Women and Style (2001) and Dress and Globalisation (2004). She edited Volume 7 of the Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion, General Editor Joanne B. Eicher and was an introductory author on Queensland Dress in Remotely Fashionable edited by Nadia Buick and Madeleine King (2012). She is currently an advisor on the new book series for Bloomsbury Visual Arts entitled Fashion in Action, Series General Editor Regina A. Root, Bloomsbury.

Article Citation

Kutesko, Elizabeth. “Dressed in Time: In Conversation with Dr. Margaret Maynard & Dr. Elizabeth Kutesko” Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 2, 2023, pp. 1-21, https://doi.org/10.38055/FS040204.

Copyright © 2023 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)