“Hombres sí/Hombres nó:” Fashioning Masculinity in Early

Twentieth Century Puerto Rico

by Antonio Hernández-Matos

ABSTRACT

In early twentieth-century Puerto Rico — a society in transition — Puerto Ricans were confronted with a modernity not totally under their control, but which they both desired and feared. In this “colonial modernity,” Puerto Ricans debated its impact, especially on gender notions, through fashion texts and images. Most of those revolved around women, their behavior, and even their physical body. However, as this paper argues, men in early twentieth-century Puerto Rico were interpellated by fashion discourses, too. From the pages of Puerto Rican periodicals, a combination of foreign and locally produced texts and images advised Puerto Ricans to be well-groomed, to care for their appearance, while, at the same time, urged them to be careful, to avoid too much finesse. Although sources are rather slim, it is possible to trace at least two clashing representations of masculinity, to distinguish fashionable models available for the Puerto Rican “modern” man, and to point out the role of consumption. This paper, first, examines how fashion advertisements, for both foreign and locally produced goods, and texts that addressed men as fashion subjects—exposed their preoccupations with their appearance, and constituted them as consumers. Second, the paper analyzes these texts and images to reveal contending conceptions of masculinity in which a “modern” masculinity is presented as weak. And, finally, this article uses the “hombres sí/hombres nó” polemic and the case of the transvestite “Mario Sacristán/María Quesada,” who for many years lived dressed as a woman to contend that, for this generation of Puerto Ricans, “masculinity” was an empty sign which fashion helped to fill in the transitional and colonial contexts of the period. The paper also tangentially contributes to the ongoing questioning of the “great male renunciation” hypothesis in fashion studies. The inquiry is done using insights from discourse, visual, and textual analysis.

Special Issue: State of the Field, Issue 1, Article 2

DOI: 10.38055/SOF010102

KEYWORDS

Fashion

Modern man

Masculinity

Puerto Rico

Colonial modernity

In the first decades of the twentieth century, discussions about fashion were an important way for Puerto Ricans to reconcile their sudden encounter with a colonial modernity imposed by the new colonial rule from the United States. Paradoxically, this imposed colonial modernity was desired for the freedoms it brought and, at the same time, feared for the unintended consequences of such freedoms, particularly regarding notions of gender.[1] Thus, Puerto Ricans appropriated transnational fashion discourses as a means of signaling their participation in an ordinary, everyday modernity of global reach in a transitional, colonial context.[2] The importance of fashion is suggested by two factors: one is the massive number of fashion texts and images published in Puerto Rican periodicals, and the other is the heated and impassioned controversies about fashion and its gendered effects that took place in their pages. As in other geographies, women were the main subjects of scrutiny and targets of fashion discourses; they experienced the full force of those discourses — whether advising women to follow a particular trend or condemning them for doing so — and the unrelenting criticisms about their “masculinization” or their display of flesh and sexual exhibitionism.[3]

However, as this essay will demonstrate, Puerto Rican men were also targeted as fashion subjects and even engaged in their own fashion discussions. The essay briefly delineates the image of the fashionable “modern man” conveyed in advertisements. It also surveys a variety of fashion texts and images to illustrate how sartorial issues connected with other men’s concerns. Finally, it focuses on discussions about the fashionable modern man and the masculinity he represented. This examination will also show that discussions about men’s fashion were scarcely formulated within a nationalist framework, which problematizes and complicates still dominant historical narratives that sustain Puerto Ricans overwhelmingly resisted the United States’ occupation of the island, painting a bleak picture of a society either dominated by political strife or by a perpetual, generalized scarcity.

[1] I take the concept of “colonial modernity” from the historiographical debate about Japanese colonialism in Korean historiography. Tani Barlow first proposed the concept to move historical studies about Japanese colonialism beyond the resistance/accommodation dyad, which, as historian Eileen Findlay has pointed out, has been prevalent in Puerto Rican historiography, too. Since colonial modernity assumes that modernity is inseparable from colonialism, colonial subjects are conceived as appropriating and resignifying modernity, not trying to poorly imitate a supposedly original one. In addition, colonial modernity emphasizes “urbanization, consumerism, mass media, industrial capitalism, and leisure in the ‘nascent “bourgeois public sphere.” E. Taylor Atkins, “Colonial Modernity,” in Michael Seth (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Modern Korean History (London: Routledge, 2016), 128. However, while Barlow stressed the political economy aspect of the concept, I focus on the discursive openings it allows — while it refers to the unequal power relation between the U.S.A. and P.R., it also points to the islanders’ agency in imagining themselves as modern subjects and allows for analyzing the unintended consequences of colonial domination and the different policies and actions that shaped it. Eileen Findlay, Imposing Decency: The Politics of Sexuality and Race in Puerto Rico, 1870–1920 (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1999), 4; Tani Barlow, “Introduction: On ‘Colonial Modernity’,” in Tani Barlow (ed.), Formations of Colonial Modernity in East Asia (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1997), 1-20; Tani Barlow, “Debates Over Colonial Modernity in East Asia and Another Alternative,” Cultural Studies, 26:5 (September 2012): 617-644; Ruri Ito, “The “Modern Girl” Question in the Periphery of Empire: Colonial Modernity and Mobility among Okinawan Women in the 1920s and 1930s,” in Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Madeleine Y. Dong, and Tani E. Barlow (eds.). The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2008), 240-262.

[2] Modernity is understood as a new consciousness and as an experience. The first allows the configuration of certain subjects “who assume and articulate their own representation,” as historian Silvia Álvarez Curbelo puts it (10). One of the elements that conformed that modern consciousness was “a positive attitude toward change guided by the idea of inexorable progress.” Silvia Álvarez Curbelo, “El afán de modernidad: la constitución de la discursividad moderna en Puerto Rico (siglo XIX)” (PhD Dissertation, University of Puerto Rico, History Department, 1998), 23. This openness to change is fundamental for fashion. Modernity as experience refers to the chaotic and paradoxical nature of modernity that Marshall Berman identified. In the case of Puerto Rico, it has been well documented that the island’s elite men and working-class leaders viewed the change of sovereignty as the opportunity to transform the island from a backward, colonial society to a modern one. Marshall Berman, “Prefacio” and “Introducción,” Todo lo sólido se desvanece en el aire: la experiencia de la modernidad (México, D.F., & Madrid: Siglo XXI Editores, 1989), XI-XII, 1-27. See also: Ángel Quintero Rivera, Conflictos de clase y política en Puerto Rico (Río Piedras: Ediciones Huracán, 1986); María Dolores Luque, “Los conflictos de la modernidad: la élite política en Puerto Rico, 1898–1904,” Revista de Indias, LVII:211 (1997), 695-727; María de F. Barceló Miller, “Domesticidad, desafío y subversión: la discursividad femenina sobre el progreso y el orden social, 1910–1930,” Op.Cit. Revista del Centro de Investigaciones Históricas, 14 (2002): 187-212; María de F. Barceló Miller, La lucha por el sufragio femenino en Puerto Rico, 1896–1935, 2da ed. (San Juan, PR: Ediciones Huracán & Centro de Investigaciones, UPR-RP, 2007).

[3] Fashion is understood as a discourse and as a technology. As discourse, it is conceived as a series of propositions and statements about dress and behavior that establish the rules and norms of fashionable modern subjectivities, and which, as Gilles Lipovetsky argues, “are constraining by nature: they carry with them the obligation that they be adopted and assimilated; they impose themselves with varying degrees of rigor on a specific social milieu.” (29). Therefore, I am considering fashion as a regulatory discourse. Moreover, fashion is conceived as one of the ways in which, in the words of Joan Scott, “subjects are constituted discursively.” (793) As technology, fashion is a mechanism that subjects have at their disposal to transform, or to exercise a certain measure of control over, their bodies and thoughts. It is a “technology of the self,” in Michel Foucault’s sense: it permits individuals “to effect by their own means or with the help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being.” (18). Michel Foucault, El orden del discurso (Barcelona: Tusquets, 1999); Gilles Lipovetsky, The Empire of Fashion: Dressing Modern Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994); Joan W. Scott, “The Evidence of Experience,” Critical Inquiry, 17:4 (Summer 1991): 773-797; Michel Foucault, “Technologies of the Self,” in Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and Patrick H. Hutton (eds.), Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 16-49.

These fashion texts and images are varied in nature — editorials, opinions pieces, newsclips, photos, cartoons, advertisements — but all deal with or illustrate dress and/or behavior. They were published in Puerto Rican periodicals — newspapers, illustrated literary journals, and politico-satirical publications — of diverse editorial lines and political proclivities (pro-statehood, pro-autonomy), circulation (local, regional, and island-wide), and frequency (daily, weekly, monthly), aimed at the lettered elite and the emergent, aspiring middle classes, mostly conceived as white.[4] Many of those texts and images were translated copies or locally produced for imported goods. However, as Argentinian sociologist Oscar Traversa argues: “for us the world begins in other places, with other bodies. But paradoxically, on paper, in our papers, those bodies resemble each other. We live the gestures of time, the same fashions, we consume the same soaps and the same jazz animated, here and there, the muscles of such different destinies.”[5] Thus, Puerto Rican periodical editors were not only literally translating into Spanish those foreign texts, but also, at the same time, they were translating discourses of modernity for their readership. Also, as The Modern Girl Around the World Research Group showed, the constitution of modern subjects was a global discursive and visual phenomenon. Nonetheless, in their writings, Puerto Rican men and women expressed their consent with, or rejection of, the available notions of masculinity.

Searching for, and Finding, Men in Fashion Texts and Images

As in other societies, one of the main mediums through which Puerto Rican men were engaged as fashion subjects was advertising.[6] As was the case with advertisements directed to women, the ads for men appealed to a man’s desire for youth, style, beauty, modernity, and, specifically for masculine consumers, power and success. Through ads, Puerto Rican men were offered a variety of fashionable dress — in colour, cut, and materials — and were instructed to always be impeccably dressed and coiffed, meaning to appear young, clean, and healthy on all occasions. Moreover, targeting the emergent middle sectors of Puerto Rican society, ads spoke of bounty and comfort, and the image of the fashionable modern man conveyed was a successful, young, attractive, relaxed, and carefree man.

Ads also prompted men to take care of their bodies, especially their hair, including facial hair. As Barbara Clark Smith and Kathy Peiss have argued, the “array of products promising to prevent baldness or restore thinning hair would show [that] men have also worried about their looks.”[7] Ads for hair and beard products — many purportedly developed “in an absolutely scientific way” according to “modern dermatology” — insisted on connecting fashion, youth, science, and modernity.[8] Others emphasized the modern quality of the stylish man. The “very twentieth-century” figure of “Stacomb” (Figure 1) pointed to qualities such as cultural refinement.[9] To the question of what kind of men readers wanted to be in real life, another of their ads proposed a modern ideal, “a modern man,” the Latin film star Ramón Novarro.[10] (Figure 2). In the latter case, in addition to the prescriptive texts found in advertisements, images and quotes from movie stars gave men (and women) — even those who might not be well versed in films — an idea of how to be modern.[11]

[6] Christopher Breward, The Hidden Consumer: Masculinities, Fashion, and City Life, 1860–1914 (Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press, 1999); Brent Shannon, The Cut of His Coat: Men, Dress, and Consumer Culture in Britain, 1869–1914 (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2006); and Alun Withey, Concerning Beards: Facial Hair, Health and Practice in England, 1650–1900 (London & New York: Bloomsbury, 2021).

[7] Barbara Clark Smith & Kathy Peiss, Men and Women: A History of Costume, Gender, and Power (Washington, D.C.: Publications Division, Department of Public Programs, National Museum of American History, 1989), 8. Baldness was such a preoccupation that even women’s pages carried advises for how to treat it. See: “Secretos de tocador,” Gráfico, (November 19, 1911).

[8] “Danderina,” Puerto Rico Ilustrado (PRI), (May 8, 1920).

[9] “Stacomb,” PRI, (November 5, 1927).

[10] “Stacomb,” PRI, (May 5, 1928).

[11] The importance of film stars as role models has been examined by historians across U.S.A. and Latino history. See: Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); Nan Enstad, Ladies of Labor, Girls of Adventure: Working Women, Popular Culture, and Labor Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999); Vicki Ruíz, “‘Star Struck:’” Acculturation, Adolescence, and the Mexican-American Woman, 1920–1950” in David G. Gutierrez (ed.), Between Two Worlds: Mexican Immigrants in the United States (Wilmington, DE: Jaguar Books, 1996), 125-147; and, Joanne Hershfield, Imagining La Chica Moderna: Women, Nation, and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1917-1936 (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2008).

Figure 1

Advertisement for Stacomb Hair Cream.

Figure 2

Ramón Navarro advertising Stacomb Hair Cream.

A 1911, unsigned poem published in El Carnaval, one of the main, widely circulated satirical journals on the island, presented the monologue of a man getting ready for a date.[12] This text reveals the crucial role clothing and personal grooming played, as the man was sure that with his “impeccable shirt/ and shining shoes” his conquest was a done deal. His outfit would vanquish any resistance from the woman because, after all the time and effort invested in getting ready for the date he would be “hypnotical.” The man of the poem exhibited a preoccupation with his wardrobe and cleanliness, knowing the effect it would have on his date. This, in turn, points to social discourses about the relationship between grooming, cleanliness, and success. He performed a kind of modern masculinity, which was discursively encouraged.[13] A cartoon in another Puerto Rican weekly (Figure 3) shows an old man — long beard, bald head, thread-bare clothes — surrounded by a pile of paper and gesturing emphatically while exclaiming: “I will sell these bills and collection letters from my tailor as old paper and with the proceedings I will make him a small partial payment.”[14] Although it is possible to imagine that a woman in his life (wife, daughter) could have accrued those fashion expenses, the use of the possessive points to him as the spender, exemplifying men’s preoccupation with fashion. Was that the future that awaited the young man of the 1911 poem?

Figure 3

“In Debt Because of Fashion.”

Although fewer than those directed at women, there was a sizable number of variegated fashion texts aimed at men. The anonymous author of an article complained about the lack of changes in men’s styles and the delay in the arrival of fashion news to the island.[15] However, the writer had compiled some news about men’s fashions to inform the readers. Another interesting aspect of this article was the information about the assorted styles for the various times and activities of the day. This recalls how fashion used to mark upper and middle-class women’s daily lives according to the time of day and activity, and does not correspond with men’s supposed adoption, in the nineteenth century, of the “business suit” as the standard dress for all occasions. The page also included a display of accessories — cufflinks, tie clips, canes, handkerchiefs — showing a preoccupation with the finishing touches of a stylish appearance.[16]

[12] Poem, El Carnaval, (May 21, 1911).

[13] There were other masculinities available to men during this period. For example, through the conversation between two friends about the coming marriage of the sister of one of them, a 1912 poem presented two contrasting masculinities: one, the drinking, betting, brawling man; the other — the one to aspire to — the working, family man. Luis Rodríguez Cabrero, “Currente Cálamo: Un consejo,” PRI, (December 21, 1912).

[14] Cartoon, Gráfico, (August 4, 1927). Italics mine.

[15] “Modas para caballeros,” PRI, (November 8, 1919).

[16] Many scholars have argued that, in face of fashion democratization at the turn of the 19th century, clothing details — cut, material, adornments — have come to serve as distinction elements. Roland Barthes, El sistema de la moda y otros escritos (Barcelona & Buenos Aires: Ediciones Paidós, 2003); Alison Lurie, El lenguaje de la moda, 2da ed. (Barcelona & Buenos Aires: Ediciones Paidós Ibérica, S.A., 1994); Ruth P. Rubinstein, Dress Codes: Meanings and Messages in American Culture, 2nd ed. (Boulder & Oxford: Westview Press, 2001); and Elizabeth Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, Rev. & Updated Ed. (London & New York: I.B. Tauris, 2003).

Other texts, focusing on individual pieces of a man’s wardrobe, connected fashion and health. In a 1925 unsigned note, after complaining about the new hairstyles for men, the author informed the reader about the advice of a British physiologist regarding men’s use of short pants to avoid varicose veins.[17] In addition, the doctor opposed the high collar as unhealthy because it reduced the absorption of ultraviolet rays and caused terrible pains, and advocated a collarless shirt similar to boys’ “mariner suits.”[18] The anonymous critic ended the text mockingly, expecting to soon see “the first parade of shorts and sailor shirts in San Juan,” implying that Puerto Rican men, at least in San Juan, were fashion informed and that some followed the trends, no matter how ridiculous they were.

In addition to texts examining style changes or innovations, Puerto Rican men were targeted as fashion subjects in pedagogical articles and notes, which served as veritable dressing and behavior manuals, much as the fashion columns directed to women. Such written pieces instructed men in the minute details of fashionable modern dressing. They were taught the “laws” of dressing appropriately for each occasion as well as to combine different clothing items to present the correct public image. Even more, men were educated in the practices and rituals of fashionable modern behavior. The “Buenos Modales” page in Puerto Rico Ilustrado (PRI) is a good example.[19] Through a series of short stories, men were coached in formal dressing or leisure attire, and in polite conversation and behavior. For instance, they were told to avoid the use of any jewelry beyond a ring, cufflinks, and a watch because it signaled a lack of propriety, meaning it was not manly to use so many adornments. The image of the fashionable modern man that emerges from those sources is one of physical neatness and polished comportment.

Beyond being passive recipients of those discussions, Puerto Ricans participated actively in them, discussing health, gender identity, and fashion concerns as clashing views about facial hair demonstrated. As Alun Withey has shown for England, between 1650 and 1900, the display of a bearded frame or a clean shaved face has been cyclical, but both always maintain their association to masculinity and sexual prowess, while simultaneously prompting controversies about men’s health and cleanliness.[20] Moreover, he demonstrates that by the end of the nineteenth century, the short-lived “Victorian ‘beard movement’” was already in decline. An anonymous poem evidences how Puerto Ricans participated in those discursive connections, through a couple’s staged debate over the man’s decision to shave his moustache.[21] The man argued that he shaved to “look more like tourists” and “based on the principles of hygiene.” However, she did not accept such reasonings and berated him, linking his moustache to his masculinity. For her, his moustache was a symbol of his manhood, and its absence was a defect, denoting a lack. She yelled back at him: “anxious I would not suffer such mockery/ of having my boyfriend shaved/ because the jíbaro is always distinguished/ for his thick moustache/ and not for his shaved face [sajonado].”[22] And a little later: “I did not think you so dumb/ (she said arrogantly)/ to get to shave!/ don’t you understand they will put you/ if you continue shaving, among women?” The unknown author used the discursive connection between facial hair and masculinity to criticize modern fashion trends; the clean-shaved man resembles a woman, rather than a (“true”) man.

[17] “Los hombres deben usar pantalones cortos,” PRI, (November 14, 1925).

[18] See also: “La abolición del cuello masculino por los elegantes,” PRI, (November 7, 1925); “Modas para caballeros” and “Cosas de la moda,” supra. Others examined the symbolism of the shirt: Jacinto Terry, “Correspondencia para todos: El vestido y el pensamiento,” PRI, (May 24, 1924).

[19] The page ran in the second half of the 1920s, at least between 1928 and 1930.

[20] Withey, Concerning Beards.

[21] “Epigramas ilustrados,” El Carnaval, (June 5, 1910).

[22] Italics in the original.

This text is one of the few in which modern masculinity appears as foreign and in direct contrast to a “native” manhood. The modern fashion trends were symbolized, in the author’s imagination, by the tourists who, as the woman on the poem said, were arriving in “terrorist fashions.” This and the reference to the clean-shaved man as “sajonado” suggests that for the anonymous author, fashionable modern masculinity was something foreign and a threat to some implied “native” manhood of luxuriant mustaches.

Fashioning Conflicting Masculinities

The modern man, who was impacted by fashion discourses, kept an eye on the latest trends, and dressed in his fitted suit with a clean, shaved face, was harshly criticized. Those criticisms were part of a wider current of anti-modern discourses, especially regarding effects on masculinity. Male fashion at the turn of the nineteenth century was criticized as representing men’s lack of “vitality,” strength, and character to deal with life’s hardships, a consequence of the modernizing processes that had pushed men into closed spaces, prompting them to lose contact with nature and historically male-oriented open-air activities where they would discover, acquire, or strengthen their innate masculinity.[23] As Tamar Garb argues: “modern man, it was widely believed, was a weak replica of his ancient forebears, […], modern man was gradually being destroyed by the effects of modernization.”[24] Since early in the twentieth century, Puerto Rico had its own proponents of these anti-modern discourses. In a text in which he condemned and, at the same time, praised American women, Tomás Carrión Maduro, legislator of the pro-statehood Puerto Rican Republican Party, complained about the Puerto Rican modern man: “the effeminacy of the contemporary man is too much. Contemporary man is a caricature of the true man. This frail, frazzled man is an affront to his sex.”[25] Carrión’s contemporaries, Luis Felipe Dessus and Pedro Manzano Aviñó, similarly described and lambasted a weak masculinity.[26] For them, modern men had been ceding not only their place in the social hierarchy but also their very own “life force.” Both portrayed a frail modern manhood of “sentimental” men, who would enshrine their own torturer because they did not have the strength, the virility to deal with life’s setbacks. Those modern men constituted “a heinous phenomenon […] weird and despicable.” For Dessus and Manzano, men had to regain their power, their position, they had “the need to be strong, especially in matters of the heart.”[27] As Manzano so clearly and harshly put it:

We then see man, already subjected to the mesmerizing power of women, ceasing to be the true man of iron will with which he achieves triumphs and climbs summits; disappearing from him the great conservative force of his indomitable courage, the powerful I who engraved on his forehead these words: ‘Man: King of Creation.’[28]

These early criticisms of modern men, men caught in women’s clutches, happened in the context of the first attempts by male allies to support legislation in favour of women’s political progress.[29]

[23] Christopher Breward, “Manliness, Modernity and the Shaping of Male Clothing” in Joanne Entwistle and Elizabeth Wilson (eds.), Body Dressing (Oxford & New York: Berg, 2001), 174-175.

[24] Tamar Garb, Bodies of Modernity: Figure and Flesh in Fin-de-Siècle France (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998), 56.

[25] Tomás Carrión Maduro, “La mujer de Norteamérica y el hombre contemporáneo,” Ten con ten (1906). As reprinted in, Eugenio Ballou (ed.), Antología del olvido (Puerto Rico, 1900–1959) (San Juan, PR: Folium, 2018), 215.

[26] Luis Felipe Dessus, “Reflexiones Corrientes: Sobre un motivo,” El Carnaval, (December 18, 1910); Pedro Manzano Aviñó, “El eterno femenino,” PRI, (September 17, 1911).

[27] Dessus, “Reflexiones.”

[28] Manzano, “Eterno.” Italics mine.

[29] As early as 1909, Nemesio Canales — Puerto Rican writer and legislator — presented legislation promoting women’s “legal emancipation.”

Figure 4

“After the Reception.”

Figure 5

Cover for the Music Sheet of “The Dude.”

Fashionable modern men were satirized in press images, too. A cartoon in one of the weeklies showed two oldish men observing three younger men walking drunk down the street (Figure 4).[30] The outfit of both sets of men differed: the three drunk youngsters — all shaved — wore a type of smoking jacket, symbolizing their quality as modern men, whilst the garments of the two older men were more “traditional.” The observer’s comment satirized modern men’s masculinity, its lack of strength, and emasculated them with the use of the Spanish diminutive (“jovencitos”).

The “Dude” — an “affected” man, carefully groomed, delicate, dressed in fitted clothes — was the caricature of such frail and impressionable men (Figure 5).[31] In one form or another, this depiction of the modern man made its way into the pages of Puerto Rican periodicals. Many images presented men in this way (Figure 6 and Figure 7); they were drawn in fine lines, carrying themselves with “affected” mannerisms, exhibiting a sinuous figure like that of the Gibson girl.[32] As if to instruct men on how to carry themselves as true men, an article reported on the advice of “two notable doctors” about how people should walk.[33] While the part on women just briefly summarize the information directed at them, the part on men dictated:

…the normal man (average life span, health, volume, weight, etc.), should walk with his head raised, without leaning to either side, and making sure that his arms mark a certain rhythm, a movement somewhat similar to that of soldiers. The arms should fall along the trunk by their own weight, without any affectation or muscular contraction. The chest should always tend to be pulled out, that is, the arms and even the shoulders should tend backwards. In this way, fatigue is avoided, and many lung diseases are postponed.[34]

Printed in Gráfico, another widely circulated satirical weekly, the text functioned as a veiled denouncement of the modern masculinity represented in the images. Men ought to avoid an affected demeanor — it was not only unmanly but also unhealthy.

[30] “Después de la recepción,” El Carnaval, (August 6, 1911).

[31] Paoletti Jo Barraclough, “Ridicule and Role Model as Factors in American Men’s Fashion Change, 1880–1910,” Costume, 19:1 (1985): 121-134.

[32] “Desde la luneta,” Gráfico, (March 31, 1912); Cartoon of José Pérez Losada, Gráfico, (April 14, 1912).

[33] “Como debemos andar,” Gráfico, (July 28, 1912).

[34] First and last italics in the original. Second and third italics are mine.

Figure 6

“Desde la luneta.”

Figure 7

Cartoon of Writer J. Pérez Losada.

Critics of the fashionable modern man in Puerto Rico participated in global discourses of masculine improvement through the arduous work and stern discipline that exercising signified, such as “Muscular Christianity” and the “strenuous life.”[35] The representation of a Puerto Rican muscular male body made its incursion into the pages of the island’s periodicals. For instance, Puerto Rican trainer Fa Solat, in his semi-regular column in PRI, promoted the practice of weightlifting and bodybuilding, providing advice and reviewing the efforts made by individuals throughout the island. Solat, in his confidence in, and commitment to, the growth of the lifting and bodybuilding sports on the island, connected — as proponents of the “strenuous life” and Muscular Christianity did in the U.S.A. — Puerto Rican men’s muscularity and masculinity with the vitality and vigor of the nation. Thus, he was committed to “cultivate more vigorous generations […] There will be strong men here.”[36] The development of an athletic, robust, muscular body signified activity, vitality, and the possession of a resolute character, and became the medicine against the malaise of a dainty and unhealthy fashionable modern manhood.

Still, such affected manhood was viewed as dangerous and perceived as being present in the streets. Early in the 1910s there was a noticeable preoccupation with masculinity in the pages of Puerto Rican periodicals.

A first cartoon (Figure 8) shows two men, side by side: the man on the left — a blacksmith — is drawn at his workplace, tools in hands, in a position that denotes strength and activity.[37] His clothes are working clothes, but what is interesting is that they expose hair-covered flesh. This man is identified as “los hombres sí” — he is the paradigm of what a man should be, the symbol of “correct” masculinity. The man on the left is not shown working but engaged in pleasure — walking his dog (a dog so slender and stylized that it looks emaciated). He is fully clothed, with no flesh shown, in a suit: broad-brimmed hat, jacket, pants, delicate tie, flower on the lapel, handkerchief, ring, pants turned up to reveal an adorned pair of shoes of medium-high heels. He has no facial hair and a well-combed hairstyle underneath his hat. Everything about his self-fashioning and comportment (the delicate way he is grabbing his dog’s leash) shouts cleanliness and delicacy. Moreover, he is drawn in profile to display his S-shape body, the famous silhouette of the Gibson girl, contrary to the “hombre sí” who was drawn from the front to show his wide figure. This man is named “los hombres nó,” indicating the undesirability of the masculinity he represents. The image suggests a working-class masculinity as the ideal one.

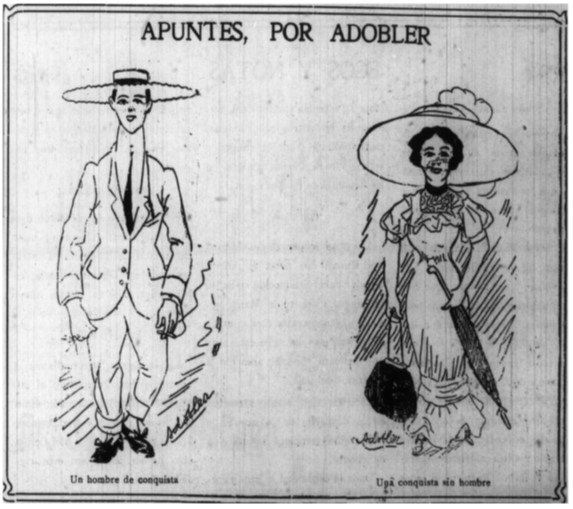

The next figure (Figure 9) shows the “hombre nó” from the front, drawn side by side with a woman donning the hobble skirt.[38] It is almost the same figure as before — same hat, same suit, same shoes — only this time he holds a cigarette in his left hand and has a shining ring on his right little finger. An important detail to be noted is his figure: he is thinner than the “hombre sí;” his shoulders are very narrow and sloped and he has a thin waist; and his hips are wider than his chest; in fact, his hips are wider than the woman’s. The caption identifies this “hombre nó” as “a man of conquest,” while the woman at his side is characterized as “a conquest without a man,” thus begging the question: if she is a woman ready to be conquered but had not been, who then, is the conquering man set out to conquer? Or, alternatively, if they are meant for each other (if she was “conquista” and he was her companion), why did the artist insist that she was without a “man”?

[35] On the “Muscular Christianity” movement, see: Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America: A Cultural History (New York, London & Toronto: The Free Press, 1996), esp. 175-183; and, Clifford Putney, Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880–1920 (Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press, 2001). Eric López examines the movement’s influence on the civilization processes Americans carried on the island at the beginning of the 20th century, in his case through the development of sports and sports related initiatives. Eric J. López Jorge, “En búsqueda del “Tom Brown” puertorriqueño: cristiandad muscular, YMCA y Boys Scouts en el proceso civilizador, 1898–1913” (MA Thesis, University of Puerto Rico, History Department, 2007).

[36] Fa Solat, “Colosos boricuas,” PRI, (August 7, 1926), as reprinted in Ballou, Antología, 234-235.

[37] “Los hombres sí… Los hombres nó,” El Carnaval, (July 30, 1911).

[38] “Apuntes, por Adobler,” El Carnaval, (August 27, 1911).

Figure 8

“Hombres sí/ Hombres nó.”

Figure 9

“Loose Notes, by Adobler.”

An article, aptly titled “Hombres sí y hombres nó,” narrativizes the contrast of the two masculinities, imbuing them with additional symbolic meanings.[39] This written portrait corresponds with the visible characteristics each man displays in the cartoons but adds new layers that the viewer cannot get from the images. According to the author, Agapito Rojas, the “hombre sí” could dress elegantly but would never present any “affectation,” while the figure of the “hombre nó” was the result of wearing a corset. The “hombre sí” spent little time and effort in his appearance, while all the gestures of the “hombre nó” were studied in front of a mirror trying to imitate women’s “charms,” and his demeanor always had “the delicate gesturing of girls.” This man, the “hombre nó,” slept with flowers and a pale light on his bedside table like a “fifteenth years-old Venus.” For the author:

…the “hombre sí” is not handsome nor can he be, he is often hairy, and has a chest full of hair. With a fixed and penetrating gaze, he seems to say to us: I have nothing of Eve and if I was born of her, it is because I transmitted the seed that fertilizes and makes men./ The ‘hombre nó,’ is something else, this one, if he had a mustache, he took it off, because a friend suggested it. He often wears patent leather chaps. He has a languid gaze and often a chaste girl’s smile is drawn on his cheeks. [...] In short, the ‘hombre sí’, [...], dominates, the ‘hombre nó,’ seduces, the ‘hombre sí’ persuades, the ‘hombre nó’ begs, the ‘hombre sí,’ commands, the ‘hombre nó,’ pleads.

Adding intangible characteristics to the images already known, the author presented the “hombre sí” as strong-willed, heterosexual, and fertile, in contrast to the easily manipulated, and effeminate “hombre nó,” thus, linking physical attributes to behavioral, moral, and ethical qualities; all “positive” in the “hombre sí” and all “negative” for the “hombre nó.”

Another text continued this contrast of masculinities. The piece examined María Luisa Zerobe’s views on men.[40] For Zerobe, a music teacher, men did not know how to make women fall in love anymore and, by the examples she gave, everything pointed to a defective or deficient masculinity symbolized in their unsuitable and unseemly way of dressing:

First visit:

Dressed in gray plaid suit; red, blue, or orange tie; wide-brimmed ashen hat, ring of diamonds and rubies.... Don’t you find these colors extremely feminine?

Second visit:

A victoria [a type of car] with a low top, light-colored pants, navy blue frock coat, patent leather boots, a red dahlia in the buttonhole... But we say, when lurking behind the curtains we see such a parrot arrive: Sir, and what do they leave us women?

[…] It is us, women, who are obliged to show off, to compose ourselves, to stretch our imagination to invent so many subtleties to enhance our charms, those charms with which we long to captivate men.[41]

Zerobe clearly portrayed fashionable modern masculinity as something akin to femininity; a weak, deficient, and possibly even deviant masculinity. This becomes clearer when contrasted with the description she made of the man whom she loved deeply. Friends and family criticized him for being “ugly” and “crude,” but he conquered her with his tough, virile qualities, symbolized in his hands: “Ah, but his hands! Wide hands, with long fingers; dark hands covered with black hair; hands with a strong complexion.”[42] The hands described were the hands of a true man who symbolized a normal/normative masculinity, which reminded the hair covered body of the “hombre sí” in Figure 8. As a contrast, representing the fashionable modern man was an unnamed pianist, who was in love with Zerobe but whom she rejected. The pianist possessed “such delicate hands. Hands of an aristocrat. […] They seemed to draw tears and sighs, rather than notes, from the piano.” Her friends praised the pianist’s hands as “the exquisite hands of an artist,” but she emphatically disagreed: “No! They are the exquisite hands of a….!!”[43] It is possible to easily imagine a series of strong adjectives to finish her thought, but the relevant issue is that the author took advantage of the story to contrast two masculinities available for men in the island, and, along the way, criticize, in no uncertain terms, the fashionable modern man, contributing another intervention in the polemic.

[39] Agapito Rojas, “Hombres sí y hombres nó,” El Carnaval, (September 3, 1911).

[40] Jorge Adsuar, “Las primorosas manos de…,” Gráfico, (October 22, 1911).

[41] Italics in the original.

[42] Italics mine. Her reference to “dark hands” should not be overlooked since it suggests a black male body as the embodiment of the “true” masculinity. Something akin was expressed in discussions about the “modern woman” on the island. This in no way means that there was no prejudice or racism expressed against non-white subjects, but it certainly complicates simplistic Manichean narratives about racial representations during this initial period of the colonial relationship. However, I can only point to the subject here.

[43] Adsuar, “Las primorosas.”

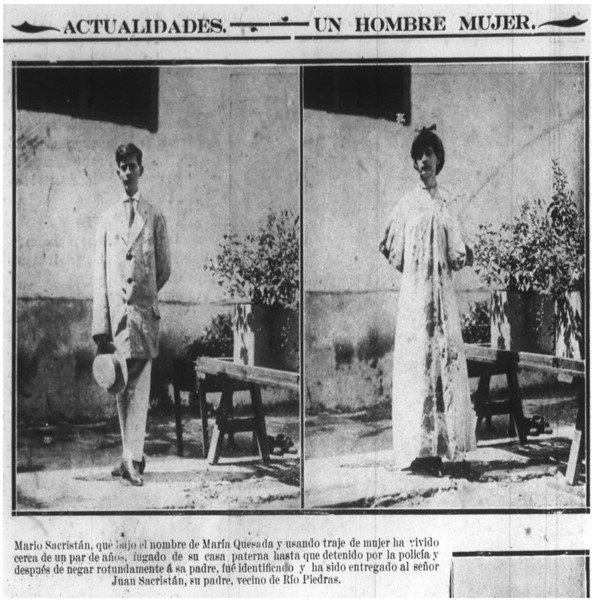

A pair of photographs (Figure 10) presented the same young man dressed two ways: on the left, the youngster wears a man’s suit, tie, and hat on hand; on the right, he dons a woman’s dress with a floral print and a bandana on his head.[44] The caption states that the young man, named Mario Sacristán, from Río Piedras, had escaped his father’s home and “has lived for a couple of years dressed as a woman,” under the name of María Quesada. The newsclip said he was arrested but did not say where or why; it did not say if he was living alone or not, either. However, despite this lack of information, for those who conceived the advent of the fashionable modern man as a struggle between a normal/normative “hombre sí” and an effeminate “hombre nó” that photo and what it represented — a man who dressed as a woman for a long time — ought to have meant a threat: how was that possible? What were the tacit agreements established between him and the community around him that allowed such a situation?[45] Then, it was reasonable to fear that an effeminate, fashionable modern man could replace the true, normal Puerto Rican man.

Figure 10

A translated headline reads: “A Female Man.”

[45] Félix Jiménez analyzes the same photo montage (although he wrongfully attributed it to PRI) within his discussion of clashing masculinities after the change of sovereignty. For Jiménez, the lack of detailed information, the focus on the return of the son, the treatment of the news as more of an entertainment incident than a scandal suggests that the motivations of Mario/María were of no interest to the periodical’s editors. He even proposes that it is possible to call into question the whole affair because the background of both photos is the same, suggesting the staging of the whole episode. Although I find his analysis compelling at times, I think Jiménez misses the mark. I would suggest understanding the report within a larger context, threading the montage with other newsclips into a quilt that would reveal an alternative reading of the photographs. Taking into account the texts discussed here, it is possible then to suggest it was not that the editors had no interest in Mario/María’s motivations but that, in fact, it was a scandal but they did not have any need to express it explicitly, that their readership would understand the contrasting images, maybe even as a warning tale of the threat that was walking among the living on the island’s streets. Félix Jiménez, “Seminales” in Félix Jiménez, Las prácticas de la carne: construcción y representación de las masculinidades puertorriqueñas (San Juan, PR: Ediciones Vértigo, 2004), 38-41.

Numerous similar texts presented cases of men dressing and even passing as women, which further prove Puerto Ricans preoccupation with the self-fashioning of gender. For our purposes, however, one example is enough: a brief report announcing the authorization obtained by “Jorge Van Zobeltitz” from the Potsdam police (Germany) to be allowed to dress as a woman.[46] Apparently, Van Zobeltitz belonged to a rich family and since childhood had liked to dress in women’s clothing, leading doctors to declare that he suffered from “an incurable, unhealthy predisposition, and that it was better to authorize what it was impossible to prevent.” Modern masculinity, being characterized as “affected” and even close to femininity, was also located close to illness. To period commentators, these were troublesome examples of men who successfully passed as women during lengthy periods of time.[47] If people were willing to tolerate — and even accept — such non-normative behavior, then perhaps it was possible that modern masculinity could establish itself as the “true” masculinity.

Finally, a 1923 cartoon portrays how such dubious masculinity could be punished. It shows a scrawny-bearded fashionable modern man being sentenced in court by a thick-mustache wearing judge (Figure 11).[48] Once again, the silhouette resembles the “Dude,” with a touch of the Flapper in its tubular shape. The thinly drawn lines and his slender outfit (fitted and with a diminutive bowtie) express his delicacy, as does his lithe demeanor (hands gently crossed in the front holding his hat, and his slightly inclined head). It could be argued that such powerlessness is expected in a courtroom but considering the image within the context discussed here opens the possibility of understanding the figure beyond the walls of the court and, instead, as an insight into his social persona, something innate to his performance of masculinity. The judge’s statement implies that the man’s transgression is fashion — and masculinity — are related; and the man must carry out his sentence in a women’s jail. In this way, the cartoonist similarly passes judgment on a “delicate,” but nonetheless, threatening masculinity.

[46] “Hombre vestido de mujer,” Gráfico, (November 23, 1913).

[47] “Hombres que han pasado por mujeres,” PRI, (September 13, 1919).

[48] “De orden superior,” El Carnaval, (June 9, 1923).

Figure 11

“Court ordered.”

Conclusion: Fashioning Masculinity in Early Twentieth Century Puerto Rico

This essay probes the place and role of fashion — as dress and behavior — for Puerto Rican men of the upper and middle classes and proves that they were represented as caring about their appearance, as they were addressed as fashionable subjects and consumers. From the pages of Puerto Rican periodicals, men were advised and coached in ways to care for their dress (of which they were offered a noteworthy variety), physical appearance, and demeanor. Many of the advertisements and texts linked that self-care with personal and business success. At the same time, this preoccupation with fashion points to Puerto Rican men’s desire of participating in an ordinary modernity of global reach in a transitional, colonial context.

However, for Puerto Rican men, this colonial modernity had some unforeseen side-effects. As in the case of women and femininity, men’s fashion was a pivotal ground for debating contrasting notions of masculinity. Of the instances examined here, there was the fashionable modern man, who was swayed by contemporary sartorial discourses and was criticized as exhibiting an affected and feeble masculinity, symbolized in the cartoonish figure of the “Dude.” On the other side, an unaffected or normal/normative masculinity was discursively displayed as an inverted mirror.

If the types drawn in the polemic were not enough to bring the point home, then the case of Mario Sacristán/María Quesada might. The case of the man who lived dressed as a woman for years embodied a real-life example of the “threat” represented by modern masculinity and the social entente for its tolerance. Within these rigorous and prescriptive social norms, Puerto Rican modern men had to walk a tightrope, keeping a balancing act between caring for their appearance but without giving the impression of effeminacy.[49]

Nonetheless, despite the fears modern masculinity provoked, discussions about the fashionable modern man in the Puerto Rican colonial modernity context were scarcely framed within a nationalist discourse. On the contrary, critics of the modern man shared their arguments with similar anti-modern tendencies found in the colonial metropolis. As opposed to other colonial and postcolonial contexts, there was no immediate development of an oppositional fashion discourse on the island nor of a national costume.[50] Once again, the sources examined here point to Puerto Rican men’s desire to, and dilemmas surrounding, fashion(ing) modern subjectivities. These findings are significant considering that still-dominant historiographical narratives in Puerto Rico argue Puerto Ricans resisted United States colonial control from the beginning through any means necessary.

This essay is a first approach to the examination of the function of fashion in early twentieth-century Puerto Rican colonial society in transition. This research examines the construction of modern subjectivities, specifically regarding the fashionable modern man and the masculinity he represented. This focus also allows for the questioning of still powerful and pervasive narratives in Puerto Rican historiography. Many topics still need to be researched: for example, working-class men’s fashion and the corresponding discourses or the plurality of masculinities performed on the island. Future projects that tap heretofore understudied sources and employ new methods and approaches will further expand our understanding of the power fashion has in the staging of a colonial modernity. Nevertheless, as this essay has shown, fashion and its gendered discourses remain a critical arena for reevaluating conceptions of masculinity, its performance, and popular representations in early twentieth-century Puerto Rico.

[49] I have to express my gratitude to anonymous Reviewer B for suggesting this line of reasoning.

[50] Many scholars have shown the political uses of fashion in different colonial and postcolonial contexts. For Latin America and the Caribbean see: Mariselle Meléndez, “Visualizing Difference: The Rhetoric of Clothing in Colonial Spanish America,” in Regina A. Root (ed.), The Latin American Fashion Reader (Oxford & New York: Berg, 2005), 17-30; Regina A. Root, “Fashioning Independence: Gender, Dress and Social Space in Postcolonial Argentina” in Root (ed.), The Latin American Fashion Reader, 31- 43; Regina A. Root, “Tailoring the Nation: Fashion Writing in Nineteenth-Century Argentina,” in Wendy Parkins (ed.), Fashioning the Body Politic: Dress, Gender, Citizienship (Oxford & New York: Berg, 2002), 71-95; Hershfield, Imagining La Chica Moderna; and Steeve O. Buckridge, The Language of Dress: Resistance and Accommodation in Jamaica, 1760–1890 (Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago: University of the West Indies Press, 2004). Dilia López and Marsha Dickson argue that Puerto Rican women exhibited signs of subtle resistance through the continued use of the Spanish hand-fan. However, what I have noticed in my research is that Puerto Rican women of the upper and middle sectors shared the desire of participating in transnational fashion discourses and fashioning modern subjectivities for themselves, a similar experience to what Ruri Ito describes for Okinawan women under Japanese colonialism. Dilia López-Gydosh and Marsha A. Dickson, “Every Girl had a Fan which She Kept Always in Motion”: Puerto Rican Women’s Dress at a Time of Social and Cultural Transition,” in Root (ed.), The Latin American Fashion Reader, 198-210; Ito, “The “Modern Girl” Question in the Periphery of Empire;” and, José F. Blanco and Raúl J. Vázquez-López, “Dressing the Jíbaros: Puerto Rican Peasants’ Clothing Through Time and Space,” in Kimberly A. Miller-Spillman, Andrew Reilly, and Patricia Hunt-Hurst (eds.), The Meanings of Dress, 3rd Ed. (New York: Fairchild Books, 2012), 379-386.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Prof. Manuel Rodríguez, for commenting on an early version of this text, and for all his help and encouragement throughout the years. Also, I want to thank my colleagues at the Centro de Estudios Iberoamericanos at the University of Puerto Rico-Arecibo for their amazing reaction to a presentation of a previous version of this text in one of our “Jornadas de Investigación.” An abridge version was presented at the 135th Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association in New Orleans. My gratitude gladly extends to Sarah Scaturro and Ann Marguerite Tartsinis for the invitation to participate in this special issue, for their insightful and incisive comments and suggestions, and above all, for their patience. Last but not least, I wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their kind words, detailed reading, and penetrating comments. This is a much better text thanks to all of them. It goes without saying that all shortcomings are entirely my fault.

Author Bio

Antonio Hernández-Matos is currently Visiting Instructor in the Department of Latino and Caribbean Studies at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. He holds a PhD in Puerto Rico and Caribbean History from the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, where he defended his dissertation, “Estas cosas parecen triviales; pero son de más importancia de lo que se cree:” Fashion, Gender, and Modernity in Puerto Rican Periodicals, 1900-1930.” He earned his master's degree in American history from the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and a bachelor's degree in secondary education with a concentration in history from the UPR-RP. He is the author of the essays “Dime cómo vistes y te diré quién eres: un acercamiento teórico a la relación moda e identidad” and “Fashion and Modernity in Puerto Rico, 1920–1930,” and has published book reviews in the journal European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (University of Amsterdam), and H-DIPLO (H-NET network). He co-authored the textbook Estados Unidos de América: trayectoria de una nación (2010 and 2015). He has presented papers at universities in the United States and Puerto Rico. His research interests revolve around the construction of subjectivities/representations in a consumer society through the analysis of the intersections among fashion, modernity, gender, sexuality, and consumption; and the Puerto Rican diaspora in the United States, its relations with consumer society, and the links between history and memory in its historiography.

Article Citations

MLA: Hernández-Matos, Antonio. “Hombres Sí/Hombres Nó: Fashioning Masculinity in Early Twentieth Century Puerto Rico.” State of the Field, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 2. no. 1, 2023, pp. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/SOF010102

APA: Hernández-Matos, A. (2023). Hombres Sí/Hombres Nó: Fashioning Masculinity in Early Twentieth Century Puerto Rico. State of the Field, special issue of Fashion Studies, 2(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/SOF010102

Chicago: Hernández-Matos, Antonio. “Hombres Sí/Hombres Nó: Fashioning Masculinity in Early Twentieth Century Puerto Rico.” State of the Field, special issue of Fashion Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/SOF010102

Copyright © 2023 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)