Things Being what they are Not: Contextualizing the “Lesbian Earring” Trend

By Lilly Compeau-Schomberg

DOI: 10.38055/UFN050109.

MLA: Compeau-Schomberg, Lilly. “Things Being what they are Not: Contextualizing the “Lesbian Earring” Trend.” Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-25. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050109.

APA: Compeau-Schomberg, L. (2025). Things Being what they are Not: Contextualizing the “Lesbian Earring” Trend. Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies, 5(1), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050109

Chicago: Compeau-Schomberg, Lilly. “Things Being what they are Not: Contextualizing the “Lesbian Earring” Trend.” Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies 5, no. 1 (2025): 1-25. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050109.

Volume 5, Issue 1, Article 9

Keywords

Lesbian fashion

Queer theory

TikTok fashion

Camp femininity

Abstract

In queer women’s fashion literature there is a tendency to focus on the utilization of masculinity to communicate a divergence from expectations of heteronormative femininity. Despite this focus on masculinity, expressions of queer femininity through dress are of equal importance. In 2020 the “lesbian earring trend” emerged on social media platforms. Earrings within this trend typically forgo the ideals of “good taste” and lean into the kitsch, the camp, and the absurd. These earrings serve as a queer identity signifier while moving away from the typical masculine dress associated with queer women. The “lesbian earring” trend allows for the expression and communication of a queer femininity by challenging heteronormative western expectations of feminine dress, particularly the notion of “good taste.” By conducting a semiotic analysis using Etsy search results, this research places the “lesbian earring” trend within the broader context of queer women’s fashion in the 20th and 21st centuries. The design elements in the earrings were considered for their overt or thematic relation to queerness. Drawing on ideas from Butler, Bourdieu, and Sontag, the construction of gender and femininity and its relation to the idea of good taste is used to explore how campiness and bad taste are used in queer expressions of identity. This research contributes to the limited literature on queer feminine fashion, expanding beyond the image of the butch or masculine lesbian.

Introduction

In June 2023, I attended the birthday party of a friend who had recently come out as a lesbian. She was delighted to find she had been given a crocheted frog as a gift. In her excitement, she exclaimed: “I love him so much I’m going to wear him as an earring!” A different guest responded, “That’s one way to tell everyone you’re a lesbian.” In this moment an online trend materialized, and the communicative power of a simple earring was solidified.

Earrings within the trend typically lean into the kitsch, the camp, and the absurd. [2] Due to the trend originating among queer people, it also serves as an identity signifier. Common queer women’s signifiers in fashion often utilize masculinity to communicate a divergence from expectations of heteronormative femininity. [3] The “lesbian earring” trend differs from this while being similarly subversive, allowing for the expression and communication of queer femininity by challenging expectations of feminine dress, while following the historical use of earrings as a method to communicate queer identity.

[1] Martine Aamodt Hess, “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings: A Celebration of Queer Trends,” Diva (July 2021), 20; Cecilia Lenzen, “TikTok Lesbians will make Earrings out of Literally Anything,” dailydot (September 23, 2020), https://www.dailydot.com/irl/lesbian-earrings-tiktok/; Sarah Prager, “Lesbian Earrings are Taking Over TikTok, and They’re Wild,” them (September 18, 2020), https://www.them.us/story/tiktok-lesbian-earrings.

[2] Hess, 20; Lenzen; Prager.

[3] Ann M. Ciasullo, “Making Her (In)visible: Cultural Representations of Lesbianism and the Lesbian Body in the 1990s,” Feminist Studies 27, no. 3 (2001), 577+.; Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas, Queer Style (2013), 23-48; Alix Genter, “Appearances can be Deceiving: Butch-Femme Fashion and Queer Legibility in New York City, 1945-1969,” Feminist Studies 42, no. 3 (2016), 604+.

The “Lesbian Earring” Trend

As of September 2020, the hashtag #lesbianearrings had over 60 million views on TikTok. [4] Featured in the tag were videos of queer people, often queer women, showing off earrings they had made from items found around the house or inexpensive items found at the dollar store. [5] Some examples include: crayons, pill bottles, plastic baby figurines, glue sticks, and Care Bear toys. [6] Creators in the tag describe their use of the trend to communicate their queer identity to others. [7] In Prager’s article for them, she interviewed several TikTokers and Etsy sellers to gather their perspectives on the trend. [8] TikToker Jordan Ingersoll said she was drawn to the trend because “it’s about being comfortable expressing femininity in a queer-coded way, instead of what you’d think of as ‘traditional femininity.’” [9] She expands, “If I were to see a girl/feminine-presenting person out in public wearing rubber ducks as earrings I would know immediately that they are a lesbian/queer.” [10] Femmes, who can be read as “straight-passing” compared to butch or more masculine queer women, are able to use the trend to communicate their queer identity. [11] The trend is not universally loved and has been criticized for perpetuating the stereotype that queer people all dress outside the norm. [12] Joyce Pan, a queer jewelry maker interviewed by Prager, said, “in my opinion, it almost perpetuates the stereotype that gay people are always quirky and different, which is not always true.” [13] Regardless, it is still used to communicate identity to others within the community.

[4] Lenzen, “TikTok Lesbians will make Earrings out of Literally Anything,”; Prager, “Lesbian Earrings are Taking Over TikTok, and They’re Wild.”

[5] Hess, “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings,” 20; Lenzen; Prager.

[6] Lenzen; Prager.

[7] Lenzen; Prager.

[8] Prager.

[9] Prager.

[10] Prager.

[11] Prager.

[12] Lenzen, “TikTok Lesbians will make Earrings out of Literally Anything,”; Prager.

[13] Prager.

This is not the first time earrings have been used by queer people as an identity signifier or flag. A single piercing in the right ear was used by gay men in the 1970’s and 80’s to communicate their identity to other gay men. [14] The use of this declined during the 1990’s as the flag became known to the general public, and earrings became more broadly acceptable for heterosexual men. [15] As a result, ear piercings for men were no longer able to communicate a lack of adherence with heteronormative expectations.

Similar to the use of earrings by gay men, the “lesbian earring” trend relies on challenging the idea of what is acceptable regarding heteronormative expectations of dress. [16] While ear piercings are normalized, the items used to make the earrings are unconventional and it is this straying from convention that allows the trend to communicate queerness.

As a queer femme myself, I have embraced this trend. I have a collection of earrings which includes daggers, tarot cards, fake teeth, and anatomical hearts. I have also seen my friends participate in or reference the trend, increasing my proximity to it. Additionally, I have long been frustrated by the focus of queer women’s fashion studies being on butches and masc women [17] because of their distinct fashion, and the accompanying conflation of femme fashion with heterosexual women’s fashion. [18] This renders femmes less visible in this academic context in addition to a lack of visibility in public consciousness. [19] From my own experience, queer femme visibility is complex. I am often read as, or assumed to be, straight by those outside the queer community whereas those within read my queerness easily. Because of this experience, I am interested in exploring signifiers within queer fashion, particularly ones that are only understood by those within the community.

[14] “A Brief History of Signaling: The Gay Ear Myth,” Queerty (April 6, 2023), https://www.queerty.com/brief-history-signaling-gay-ear-myth-20220130; Trish Hall, “Piercing Fad is Turning Convention on Its Ear,” The New York Times (May 19, 1991), https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/19/news/piercing-fad-is-turning-convention-on-its-ear.html.

[15] “A Brief History of Signaling: The Gay Ear Myth”; Hall.

[16] Hess, “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings,” 20; Lenzen, “TikTok Lesbians will make Earrings out of Literally Anything”; Prager, “Lesbian Earrings are Taking Over TikTok, and They’re Wild.”

[17] Butches and mascs are queer people who prefer a style of dress which is considered masculine in their cultural context. These terms are often used by lesbians but are not exclusive to queer women.

[18] Geczy and Karaminas, Queer Style, 24.

[19] Genter, “Appearances can be Deceiving,” 604+.

While queer people of many genders participate in the lesbian earring trend, I will be focusing on queer women and using the terms “queer woman” and “lesbian” interchangeably in my discussion. Regarding sexuality, I am using “queer” as an umbrella term to mean non-heterosexual. While I will be using the term lesbian, I do not have a clear definition based on attraction. Rather, “lesbian” refers to those who identify as lesbians. While often these are women who are exclusively attracted to other women, or non-men attracted to non-men, rigid definitions such as these allow for exclusion. By defining the term as a self-designated identity, I hope to remain as inclusive as possible of the diverse manifestations of lesbianism and queer femininities in my writing.

Dress, Fashion, and Clothing

While this is not a phenomenological paper, I do draw my understanding of dress and fashion from embodiment scholar Joanne Entwistle. Dress is understood by Entwistle as a “situated bodily practice.” [20] It cannot be removed from the body. Dress and discourses of the body are heavily gendered, [21] connecting clothing and dress to how gender is communicated and understood. Garments and clothing are the items when not being worn, but dress is the act of wearing. [22] The body of the wearer informs how the clothing is understood when worn. [23] The same garments worn by two different people will be interpreted differently. [24] This is of particular relevance when considering the semiotic value of clothing as the wearer themself will influence how the sign is interpreted.

“Fashion” is not synonymous with dress or clothing. Rather, the word refers to the systems through which dress gains meaning. [25] Fashion is what allows clothing to be used to communicate. While fashion, clothing, and dress are colloquially interchangeable, their definitions here are more specific. Drawing on Entwistle, an example of the three coming together is that of a bride and a wedding dress. [26] A white gown on its own is just a garment, but once worn, the dressed woman becomes a bride. Through the act of wearing the white gown in the context of a wedding, the woman communicates an aspect of her identity at that moment. Fashion is what allows onlookers to understand the meaning of a woman in a white gown. Fashion, dress, and clothing are all important in understanding the “lesbian earring” trend and how it functions as a queer signifier. Clothing is the earring as an item, dress is wearing the earring, and fashion is the language that imbues this act of dress with meaning.

[20] Joanne Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body: Dress and Embodied Practice,” Fashion Theory 4, no. 3 (2000), 325.

[21] Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 328.

[22] Joanne Entwistle, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory (2nd ed.), (2015), 3, 40-43.

[23] Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 341.

[24] Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 341.

[25] Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 329; Entwistle, The Fashioned Body, 3.

[26] Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 338.

History

In order to understand how the lesbian earring trend fits within the larger context of queer women’s fashion, I will address the modern history of the topic in a North American Context. While queer women’s fashion varied throughout the twentieth century, a common theme was incorporating pieces traditionally associated with masculinity. This is seen in the early stereotype of the “sexual invert” prevalent in the early twentieth century. [27] Lesbians were considered a “third sex,” outside the male/female binary and were understood as “mannish.” [28] This notion of queerness as a third sex or gender—as at this point in history sex and gender were perceived as synonymous—connects heterosexuality with societal understandings of gender, meaning that to be a woman one must be attracted to men and vice versa. By not being heterosexual, lesbians were not seen as women, which was reflected in their adoption of masculine dress.

Beginning in the 1940’s through the 1960’s there was the rise of the butch/femme dynamic, which began in working-class bar culture. [29] In the literature on the history of queer women’s fashion, greater attention is paid to the dress of butches. [30] This is in part because of their visibility outside of lesbian spaces. Like the previous image of the sexual invert, butch fashion utilized masculine items of clothing to communicate queerness. [31] Mirroring the lesbian fashion phenomena of earlier in the century, masculinity was used here to communicate queerness by subverting gendered expectations of dress. Femmes were often considered less “visibly queer” because their fashion did not outrightly challenge gendered expectations of dress and, as a result, they could “pass” as straight. [32] They were only seen as queer when alongside a butch. [33] Although femme queerness was not as clearly communicated to the onlooker, they did nonetheless make their own efforts to visualize their sexuality through dress.

[27] Geczy and Karaminas, Queer Style, 25; Geertjie Mak, “Sandor/Sarolta Vay: From Passing Woman to Sexual Invert,” Journal of Women’s History 16, no.1 (2004), 55-56.

[28] Geczy and Karaminas, 25.

[29] Geczy and Karaminas, 32.

[30] Geczy and Karaminas, 32-34; Vänskä, Annamarie. “From Gay to Queer- Or, wasn’t fashion always a very queer thing?” Fashion Theory 18, no. 4 (2014), 447-463.

[31] Geczy and Karaminas, 32.

[32] Genter, “Appearances can be Deceiving,” 615.

[33] Genter, 615.

From the 1960’s through to the 80’s, there was a transition from butch/femme towards androgyny and “anti-style,” particularly among lesbian feminists. [34] Participating in the fashion system was understood to be feeding into an oppressive patriarchal system. [35] This changed in the 1990’s, with the image of “lesbian chic” coming into the mainstream. [36] This image was thin, white, middle- to upper-class, and rose out of the popularity of androgyny for straight women. [37] There was also a resurgence in butch/femme roles and fashion, though less rigidly divided and allowing for more fluidity. [38] While lesbian chic brought the image of queerness into the mainstream through commercialization, the stereotype of the lesbian outside of the high-fashion world was still understood as butch and masculine. [39] This contrasts the depiction of lesbian chic as an accepted expression of queer femininity.

Throughout the 2000’s, there have been various fashion trends connected to queer women. More recent queer women’s signifiers include undercuts, one nail painted a different colour, or the “bisexual jean cuff”. [40] Of these, the single nail painted a different colour, has lost its tie to queerness as it was adopted into the mainstream as an “accent nail manicure.” [41] With the current rapid trend cycle and spread of aesthetics through social media, the lifespan and function of a queer signifier is questionable.

[34] Geczy and Karaminas, Queer Style, 34-35.

[35] Geczy and Karaminas, 35.

[36] Geczy and Karaminas, 42-45.

[37] Geczy and Karaminas, 37-40.

[38] Ciasullo, “Making Her (In)visible”; Geczy and Karaminas, 37, 42.

[39] Geczy and Karaminas, 47.

[40] “The Life and Death of Femme Flagging.” Into (May 28, 2018), https://www.intomore.com/culture/the-life-and-death-of-femmeflagging/; Jennifer Wilber, “10 Things That Are Bisexual Culture,” Paired Life, (June 25, 2023), https://pairedlife.com/gender-sexuality/10-Things-that-are-Bisexual-Culture.

[41] “The Life and Death of Femme Flagging.”

Semiotic Analysis

My interest is in how the “lesbian earring” trend is able to communicate queerness. As a sign system, clothing is limited and imperfect. [42] What clothing is able to communicate is limited and dependent on the receiver understanding the sender’s intended sign. [43] It is also dependent on context, including time, location, and wearer, as this can impact how a signifier is interpreted. [44]

There is also the issue of intent. Clothing is not only used for communication, so a person may wear a certain item with no intent to send a message, resulting in perceivers falsely interpreting a signifier. [46] These intricacies within the semiotics of fashion make this analysis inconclusive and, as a result, this research will not provide a universal guide of how to communicate queerness with earrings but rather highlights common themes within the trend which may be used to communicate queer identity.

For the “lesbian earring” trend, there is the chance of the signifier being misinterpreted. Specifically, a person may have an eclectic fashion sense and be drawn to the aesthetics of the trend without being queer or even being aware of the associations of queerness with specific fashion objects. There is also a history of queer women’s signifiers, especially femme signifiers, being adopted into the mainstream and losing their functionality. [47] If enough people outside the community partake in the trend for aesthetic reasons only, the ability to effectively communicate is lost. [48] At this point it is unclear if the trend will continue to function as a queer signifier in the future.

[42] Fred Davis, “Do Clothes Speak? What Makes them Fashion?” Fashion Theory (Malcolm Barnard, ed.) (2007), 227.

[43] Davis, 227.

[44] Colin Campbell, “When the Meaning is not a Message: A Critique of the Consumption as Communication Thesis,” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.)

[45] Malcolm Barnard, “Fashion: Identity and Difference,” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.) (2020), 259-266; Roland Barthes, “The Analysis of the Rhetorical System,” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.) ( 020), 220; Davis, 227.

[46] Malcolm Barnard, “Fashion as Communication Revisited,” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.) (2020), 249; Campbell, “When the Meaning is not a Message,” 243.

[47] Hess, “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings,” 20; “The Life and Death of Femme Flagging.”

[48] “The Life and Death of Femme Flagging.”

Methodology

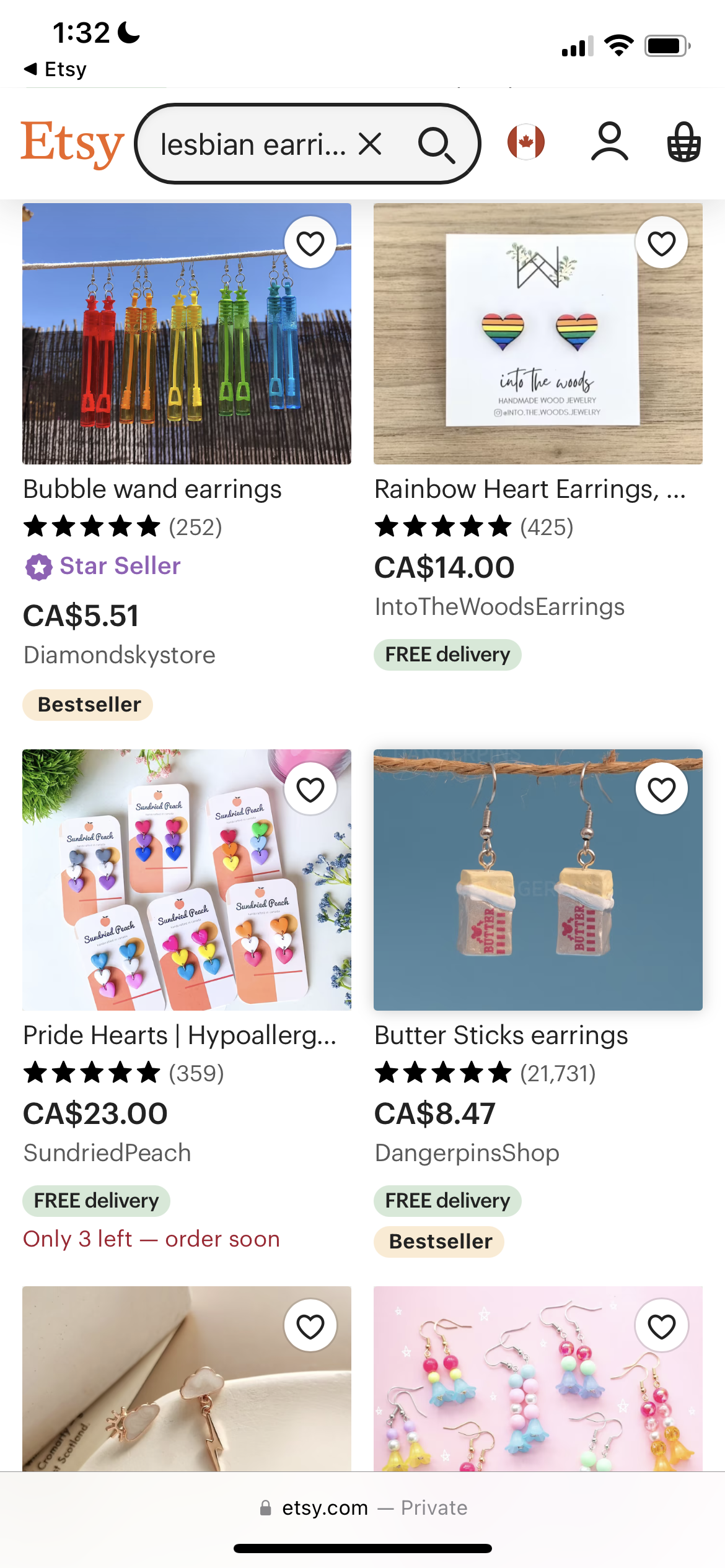

For this semiotic analysis, I analyzed the search results of the search term “lesbian earrings” on Etsy. I conducted this search on an incognito tab while logged out to ensure my personal data history on the site did not alter my results. Etsy was chosen as the platform because its search results garner images and because there is no question about their public nature, as was raised in McKee and Porter. [49] It is also mentioned in articles by Lenzen and Prager as a site used by queer people to sell earrings that align with the trend. [50] The purpose of the platform is ecommerce, and these images are put online in the hopes of being seen by others to promote sales. In my choice of platform, I am minimizing privacy concerns.

An aspect of the “lesbian earring” trend is a DIY aesthetic that separates it from mainstream expectations of feminine beauty. [51] Resulting from this, some queer women make the earrings themselves to participate, while others sell their creations on Etsy. [52] Because Etsy allows for individuals to create and sell their own work, available styles may not be found in mainstream stores. On Etsy, we can see the types of earrings queer people are selling and buying from each other rather than what is being sold and marketed by corporate executives, resulting in a more natural depiction of how the trend is participated in by the queer community.

Unlike what is described by Pennington, [53] I am not considering the composition of the images in my analysis. My focus is with the earrings themselves and how they act as signifiers for queerness. [54] The text accompanying the images, or what Pennington describes as the anchorage, [55] is used as the filtering tool. All images analyzed came up when searching for the term “lesbian earrings,” so there must be some relation whether in the title, description, or tagging of the item. This provides context to the images, clarifying what may be signified.

For my images, I screenshotted the first three pages of my Etsy search results. This search was done on April 4, 2023. In total, there are 32 screenshots with 143 listings, resulting in 135 unique images of jewelry, primarily earrings. This was more data than I needed; however, in having such an abundance, certain themes became more pronounced than others. As suggested by Pennington and Recuber, [56] I formulated my themes after collecting the images and seeing what commonalities emerged. I initially found three themes, keeping with Recuber’s recommendation of limiting the number of categories, [57] but these were later divided as there were distinct groups within these broader categories.

[49] Heidi A. McKee, and James E. Porter, “Rhetorica Online: Feminist Research Practices in Cyberspace,” in Rhetorica in Motion: Feminist Rhetorical Methods & Methodologies (Eileen E. Schell and K.J. Rawson, eds.) (2010), 157-58.

[50] Lenzen, “TikTok Lesbians will make Earrings out of Literally Anything.”; Prager, “Lesbian Earrings are Taking Over TikTok, and They’re Wild.”

[51] Hess, “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings,” 20.

[52] Hess, 20.

[53] Diane Rasmussen Pennington, “Coding of Non-text Data,” The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods (Luke Sloan, Anabel Quan-Haase, eds.) (2017), 240.

[54] Pennington, 240.

[55] Pennington, 241.

[56] Pennington, 240; Timothy Recuber, “Digital Discourse Analysis: Finding Meaning in Small Online Spaces,” Digital Sociologies (Jessie Daniels, Karen Gregory and Tressie McMillan Cottom, eds.) (2017), 53.

[57] Recuber, 53.

Results

As someone personally familiar with the “lesbian earring” trend, there were certain themes I was anticipating, like particular objects (e.g., trinkets, small toys, figurines) and pride flags. The three main themes observed were identified as Pride, Objects, and Nature, though some examples fit into more than one category. Within Pride were three subcategories: flags, lesbian flags specifically, and non-flag pride. Flags included the standard rainbow flags for LGBTQ+ pride or other rainbow-coloured items, as well as non-lesbian pride flags. Earrings coloured to be reminiscent of a pride flag are included here. Posts which depicted multiple pride flags were grouped here even if the lesbian flag was depicted. Lesbian flags were exclusive to earrings including the lesbian flag colours. This was prominent enough to warrant its own category, likely because of the search term used. For non-flag pride, there were depictions of Sappho, of women embracing, and most commonly of the Venus symbol, either alone or two interlocking figures.

Objects was similarly divided into two categories: representative and actual. Representative refers to objects that are depictions of something, rather than the item itself. Examples include miniature sticks of butter, miniature cassette tapes, and tiny plastic babies. There was a notable number of weapons such as swords, daggers/ knives, axes, and guillotines included in this category. The subcategory of actual constituted items that were not a replication, but rather the item itself. Examples include dice and bubble blowers.

The final category was Nature, which was divided further into cottagecore and celestial aesthetics. Cottagecore refers to earrings which drew on the “cottagecore” aesthetic as described by Hess; [58] frogs, mushrooms, moths, and flowers. Earrings in the celestial category include moons and suns.

[58] Hess, “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings,” 21.

The table below (see Table 1) expresses the breakdown of each category and its relevant search results:

table 1

Breakdown of earring category and number of relevant search results.

Pride related earrings were the most prominent, with the majority being general pride flags. Objects (actual) and Nature (celestial) were the least common. There were 22 examples grouped into two categories, often because they were an object with pride colours. For this article, I will focus on the Object category.

Some objects have a potential connection to queerness that may be as obvious as those grouped under Pride (non-flag). These would be scissors and axes. The scissors could be referencing tribadism or “scissoring,” a sex act associated with lesbians and queer women, though often not in a positive manner. [59] Axes, particularly double-sided ones, may refer to the labrys flag. This early lesbian pride flag featured a white labrys (double-sided axe) on an inverted black triangle with a purple background. [60] This flag and the labrys have been adopted as symbols by trans-exclusionary groups so I hesitate to consider it a queer symbol, though I cannot disregard its history. [61] These objects have questionable acceptance as current queer symbols though it is possible they may be read as such.

[59] Nadège, “The Sex Act You’ve Never Heard Of That’s Haunted Queer Women For Centuries,” Medium (June 8, 2020), https://medium.com/pleasure-science/the-sex-act-youve-never-heard-of-that-s-haunted-queer-women-for-centuries-2439301f7af9.

[60] “LGBTQ+ Symbols & Meanings”; Aryelle Siclait and Naydeline Mejia, “The History and Meaning Of The Lesbian Pride Flag Is Nuanced And Ever-Evolving,” Women’s Health (June 22, 2022), https://www.womenshealthmag.com/life/a36523338/lesbian-pride-flag-meaning/.

[61] Siclait and Mejia.

Depictions of axes also fell within the many earrings representative of weapons. The first pair of earrings in my search were guillotines, and in total eight results featured weapons. Guillotines may connect to the notion of “eat the rich” and leftist politics, as it is not uncommon in online spaces for people to joke about bringing back the guillotine à la French Revolution. [62] As for the other weapons (e.g., swords, daggers, knives, chainsaws), these may be prevalent because of their connection to violence and therefore masculinity.

In North America, violence and the tools used to implement violence are associated with men and masculinity. [64] By taking the signifier of masculinity (weaponry) and utilizing it with a signifier of femininity (earrings), queerness is communicated using similar subversive principles as lesbian fashion in the early to mid-twentieth century.

[62] Kim Kelly, “How the French Revolution Is Inspiring Today’s Online Anti-capitalists,” TeenVogue (November 26, 2019), https://www.teenvogue.com/story/eat-the-rich-guillotine-anti-capitalists.

[63] Geczy and Karaminas, Queer Style, 25-34; Genter, “Appearances can be Deceiving,” 607.

[64] Mia Schöb and Henri Myrttinen, “Men and Masculinities in Gender Responsive Small Arms Control,” Gender Equality Network for Small Arms Control (March 2022), https://gensac.network/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Men-and-Masculinities_final.pdf.

Other objects, such as safety pins or dice, may pertain to subcultures or hobbies and identities outside the mainstream. Safety-pin earrings have connections to punk. [65] As for the dice, they are commonly used in Table-Top Role Playing Games (TTRPGs) such as Dungeons & Dragons. [66] Both punk and TTRPGs have been associated with various subcultures in the late twentieth century. [67] Earrings made with these items may position the wearer as outside the mainstream and as a part of the subculture being depicted in addition to communicating their queerness. This is particularly true for examples that combined a subculture-associated item with pride flag colours, as they more explicitly communicated both queer identity and group affiliation.

The majority of the objects were representative rather than actual. Part of the reasoning for this division may be practicality. The “bubble wand earrings” (fig. 1) are the actual item, but because they are smaller and lightweight they are feasible to be worn as earrings while still maintaining their functionality. Comparing these to the “butter sticks earrings” (fig. 1), these are representative figurines that depict butter sticks because wearing actual sticks of butter as earrings is likely impossible and inadvisable. I suggest that these items are chosen because they are “camp” or otherwise fall outside western expectations of femininity. The feminine signifier is made to communicate queerness not because it depicts queer symbols or draws on masculinity, but because it goes out of its way to not draw on heteronormative expectations of feminine beauty.

[65] Sharon M. Hannon, Punks: A Guide to an American Subculture, (2010), 53.

[66] Rick Heinz, “Why Do We Use Dice in Tabletop RPGs?” Nerdist (April 11, 2019), https://nerdist.com/article/dice-tabletop-game-masters-hall-sponsored/

[67] Monica Sklar et al., “Fashion Cycles of Punks and the Mainstream: A US Based Study of Symbols and Silhouettes,” Fashion Practice 13, no. 2 (2020), 255; Sarah Whitten, “Dungeons & Dragons had its Biggest Year Ever as Covid Forced the Game off Tables and onto the Web,” CNBC (March 13, 2021), https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/13/dungeons-dragons-had-its-biggest-year-despite-the-coronavirus.html.

I had anticipated more actual objects than resulted from my search. This may be because earrings of this type are not as easy to sell, thus are less prevalent on an e-commerce platform. I was also surprised by the prevalence of weapons in the replicated objects category. This is something I had seen before, but I was unaware of how common the theme was. Lastly, I was surprised how few unconventional objects there were, like the “plastic baby earrings” (fig. 2). Due to my familiarity with the trend, I associate it with objects like this. For there to be so few of these objects, and for them to appear so late in the search results, was unexpected. Again, this may pertain to the fact I conducted this search on an e-commerce platform. There is an algorithm that determines which results show first from a search, in addition to paid advertisements. Earrings like the “plastic baby earrings” may not sell as well, therefore being relegated to appear later in search results, and similar earrings may be shown in pages beyond the scope of my data.

figure 1

Screenshot of Etsy search results for "lesbian earrings." Includes earrings made from small bubble wands and miniature butter sticks. Lilly Compeau-Schomberg, Etsy Screenshot Number 18, April 4, 2023.

figure 2

Screenshot of Etsy search results for "lesbian earrings." Includes earrings made from small plastic baby figurines. Lilly Compeau-Schomberg, Etsy Screenshot Number 30, April 4, 2023.

Limitations

This analysis is limited by my choice of using Etsy as the primary e-commerce platform for my research. While it does minimize privacy concerns, the items shown from my search were determined by Etsy’s algorithm and my choice of search term. Including the term “lesbian” in my search may have resulted in more pride flags. Additionally, some sellers may have included the terms “lesbian earring” in the item entry or tags without said item meeting my understood criteria of “lesbian earrings.” Advertisements impacted the results as well, with some posts showing multiple times. Etsy also notes “star sellers,” who have a proven customer service record, [68] and featuring these star sellers likely resulted in the promotion of certain items. The search term used, advertisements, and Etsy’s algorithm influenced which items were shown in my search.

Etsy’s terms of service likely also limit what is posted on the site. In their terms of service, “items that contain racial slurs or derogatory terms in reference to protected groups” are banned. [69] There may be homemade earrings that fit within the trend but use language that may be banned under this rule. As a result, they cannot be sold on Etsy and cannot be included in this analysis. There are also restrictions on “mature content,” [70] defined as “printed or visual depictions of human genitalia, sexual activity or content, profane language, sexual wellness items, violent images (within reason; see also Violent Items), and explicit types or representations of taxidermy.” [71] This restriction is broad, and while it does not ban this content from Etsy it may limit its appearance in search results or discourage sellers from posting it. Lastly, “items that encourage, glorify, or celebrate acts of violence against individuals or groups” are also prohibited. [72] This may prevent earrings which draw more heavily on the “eat the rich” notion or on the popular catchphrase “be gay do crime,” [73] as both could be seen as promoting violence.

[68] “What is the ‘Star Seller’ Badge?” Etsy (n.d.) [accessed May 13, 2025], https://help.etsy.com/hc/en-us/articles/4403058372503-What-is-the-Star-Seller-Badge?segment=selling.

[69] “Prohibited Items Policy,” Etsy (June 5, 2023) [accessed July 3, 2023], https://www.etsy.com/ca/legal/prohibited#Q7.

[70] “Prohibited Items Policy.”

[71] “Prohibited Items Policy.”

[72] “Prohibited Items Policy.”

[73] The phrase “be gay do crime” has been in use for many years but rose in prominence in 2018. It points to the history of queer identities being criminalized and encourages people to fight against unjust laws. Kevin Maimann, “Where Does ‘Be Gay, Do Crime’ Even Come From?” Xtra (March 5, 2024), https://xtramagazine.com/culture/be-gay-do-crime-explained-263699.

Performing the analysis on another site such as Instagram would likely have yielded different results. The primary purpose of Etsy is to act as a marketplace so only earrings which can be sold or are commercially viable are included. This is restrictive and has the potential to uphold systemic biases that favour those in privileged positions. Sellers with the finances to pay for advertisements may have a further reach and prioritized placement in search results. Use of unconventional items may make them less commercially successful. Past posts which did not sell may have been taken off the site. Personal creations, such as earrings made from empty prescription bottles are not allowed to be sold. There may be some sellers from outside the community tagging their listings as “lesbian earrings” to reach and profit from the queer community. The commercial viability of the earrings on Etsy limits what will be shown or included which is not true for other sites which are not restricted by the purpose of being a marketplace. Conducting a similar analysis on a different website may highlight the specific ways the forces of capitalism impacted my results by providing a new perspective.

Discussion: What Makes the Trend Queer

The semiotic analysis provided some examples of what is included in the trend, as well as how the trend can be used to communicate queerness. The following section considers its place within the broader context of queer women’s fashion.

Legacy of Queer Earrings

As previously mentioned, there is a history of earrings being used as a signifier of queer identity, primarily by gay men. [74] Prior to the flag becoming known to the broader public, it allowed for the communication of identity only to others in the know. Earrings are a small, inconspicuous accessory that can easily be removed or changed. The earring as a signifier takes on new meaning under the “lesbian earring” trend as it is not having a specific piercing itself that communicates identity, but rather the style of jewelry worn.

[74] “A Brief History of Signaling: The Gay Ear Myth.”; Hall, “Piercing Fad is Turning Convention on Its Ear.”

In western culture, earrings are culturally coded as feminine. For gay men, wearing a feminine-coded accessory transgresses expectations of masculine appearance, thus communicating queerness. This is the inverse of the notion of queer women utilizing masculinity previously discussed. In this context, earrings on a feminine body are not inherently transgressive and do not communicate the challenge of heteronormativity—the unconventional designs and motifs of the earrings themselves are what allow them to serve as a signifier of queer identity.

Visually, complying with these norms through dress communicates heterosexuality, as they are rooted in heterosexual patriarchy. The “lesbian earring” trend eschews convention and is distinct from the norm. It is through this break from normativity that it can function as a queer signifier, rather than its transgressions of gendered expectations like earrings for gay men.

Regardless of their differences in function, both uses of queer earrings have been used to communicate identity. This is because they are known identity flags to the desired group. For gay men, the use of the earring fell out of fashion as its meaning became known, thus eliminating the subtlety of identification that the trend relied on. [75] For the “lesbian earring” trend, its meaning is clear from its name. There is not the same element of secrecy. This could reflect a broader change in public attitudes towards queer people that allows the association of the accessory to be made clear. It may also be in part due to the origination of the trend online where the clear naming allowed for a rise in visibility.

Like the gay men’s use of earrings, the “lesbian earring” has decreased in popularity, though its life cycle has been far shorter. Google Trends search results show the trend peaking from May-August of 2020. [76] It has since fallen dramatically, failing to surpass one quarter of the peak popularity since 2021. [77] It is likely that different factors influenced the decline of “lesbian earrings” compared to the gay men’s earrings. Covid-19 lockdowns may have encouraged earring making as a form of creative expression that was accessible within the spatial limitations of the time. The increasingly rapid trend cycle attributed to the global rise in fast fashion may have also been a contributing factor. Regardless of the reasoning, both uses of earrings to communicate identity from gay men, lesbians, and other queer people demonstrate how a small, otherwise inconspicuous accessory can be a valuable tool of communication.

[75] “A Brief History of Signaling: The Gay Ear Myth.”; Hall, “Piercing Fad is Turning Convention on Its Ear.”

[76] “Lesbian Earrings.” Google Trends (n.d.) [accessed April 4, 2025], https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=lesbian%20earrings&hl=en-US.

[77] “Lesbian Earrings,” Google Trends.

Camp

What is “camp”? While it can be challenging to pinpoint exactly what camp is, camp is best understood as heightened artifice and extravagance. [78] “Bad art,” or kitsch, can be considered camp, though not always, and “good art” still has the potential to be camp. [79] It is not necessarily connected to high or low culture; Sontag lists both Swan Lake and Flash Gordon comics in her canon of camp. [80]

[78] Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’,” (1964), 1, 7, https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf.

[79] Sontag, 3.

[80] Sontag, 2-3.

The artifice of camp extends to ways of seeing people and objects as, “Being-as-Playing-a-Role.” [82] Campiness can either be done intentionally or naively, with naive camp done with the intention of seriousness. [83] Ultimately, camp is failed seriousness. [84]

Sontag gives Art Nouveau as an example of an aesthetic movement built on camp. [85] She uses it to explain the style of camp as “things-being-what-they-are-not.” [86] This applies to the “lesbian earring” trend. In Art Nouveau, an object becomes something it was not intended to be, like Schiaparelli’s shoe hat. [87] In the “lesbian earring” trend, objects that are not intended to be earrings are made into earrings, employing a similar design ethos. The trend is intentional rather than naive camp, taking a lighthearted and playful approach to its aesthetic. Art Nouveau and the “lesbian earring” trend share similar design sensibilities in their transformation of objects into something new, and in this the trend intentionally employs a camp lens.

[81] Sontag, 9.

[82] Sontag, 4.

[83] Sontag, 6-7.

[84] Sontag, 10.

[85] Sontag, 3-4.

[86] Sontag, 3.

[87] Elsa Schiaparelli, “Hat,” The Met Museum (n.d.) [accessed July 30, 2023], https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/83437.

Camp and Subverting Femininity

Historically, masculinity was used to communicate queerness for women because of how sexuality is connected to gender. [88] By excluding people who are not heterosexual from the gender binary, heterosexuality becomes a constituting factor of gender. To be a woman or to be a man, then, is to be straight. By drawing on masculinity, queer women were able to communicate that they did not meet this criterion of womanhood. Subverting expectations of gender presentation communicates that expectations of gendered desire or action are not met.

Various factors (whiteness, middle class, able-bodied, thinness, heterosexuality, and cisgenderedness) come together to construct the ideal woman and ideal femininity. [89] This is then presented as a natural category of “woman,” and the constituting factors are ignored or forgotten. Camp is artifice, so employing camp in presentations of femininity highlights the artifice and instability. Masculine dress on a feminine body challenges expectations of feminine presentation by forgoing femininity, thus communicating queerness. Camp utilizes femininity to communicate queerness by heightening the artifice, calling the idea of womanhood as natural into question.

Sontag’s assertion that camp in a person is, “Being-as-Playing-a-Role,” is of note. [90] Utilizing femininity in a campy way is to “put on” the role of woman or femme. It is not an enactment of something natural and innate, but rather a performance. This shares some similarity with Butler’s understanding of performativity. Performativity for Butler is not something that can be put on and taken off; rather, it is the process through which gender is constructed and internalized. [91] What this shares with camp is that it is not a natural and innate quality. [92] Gender is artificial and acted out. [93] Camp is this artifice heightened and performed in the colloquial sense, and femininity is something that is intentionally carried out and not passively enacted.

[88] Geczy and Karaminas, Queer Style, 25.

[89] Laura T. Hamilton et al., “Hegemonic Femininities and Intersectional Domination,” Sociological Theory 37, no. 4 (2019), 322.

[90] Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’,” 4.

[91] Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988), 522.

[92] Butler, 522.

[93] Butler, 520.

By subverting expectations of feminine appearance, the category of “woman” and its co-constituting factors are recognized as artificial. Heterosexuality and queerness are not visible in the same way as masculinity. By using dress, and in this case the “lesbian earring,” to destabilize the idea of “woman,” the assumption of heterosexuality is lost. As the “lesbian earring” trend does not support hegemonic feminine beauty standards and expectations, which heterosexuality is a part of, it is instead able to communicate queerness.

Conclusion

Gender is not an innate and natural phenomenon but is socially constructed, performed, and communicated in large part through dress. [94] Gendered expectations of dress allow this system to be upheld while allowing for deviations from the norm that communicate different embodied identities. Historically, queer women have used masculine dress to communicate their queer identity. The current “lesbian earring” trend takes a different approach. This trend continues the history of earrings serving as a signifier of queerness and utilizes camp to heighten the artifice of femininity. By bringing attention to this artifice, the understanding of “woman” as a natural category is destabilized. Heterosexuality is connected to this understanding of womanhood, so by demonstrating that femininity is artificial, queerness is communicated.

[94] Butler, 522; Entwistle, “Fashion and the Fleshy Body,” 341.

Femme has been an important identity category throughout the twentieth century for queer women, but its fashion has been overlooked in favour of its more visible butch counterpart. Femininity is not limited to heterosexuality and queer femme fashion is not synonymous with straight women’s fashion. By drawing on the history of queer signifiers and leaning into the artifice of femininity, the lesbian earring trend uses camp to become a queer femme signifier. While this trend may not last as a signifier of queerness, its documentation solidifies its place in the canon of queer fashion, expanding the image of a lesbian beyond butch.

Bibliography

“A Brief History of Signaling: The Gay Ear Myth.” Queerty (2023, April 6): https://www.queerty.com/brief-history-signaling-gay-ear-myth-20220130.

Barnard, Malcolm. “Fashion as Communication Revisited.” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.), (2020): 247-258. Routledge.

Barnard, Malcolm. “Fashion: Identity and Difference.” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.), (2020): 259-268. Routledge.

Barthes, Roland. “The Analysis of the Rhetorical System.” In Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard ed.), (2020): 212-224. Routledge.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (1988): 519-531.

Campbell, Colin. “When the Meaning is not a Message: A Critique of the Consumption as Communication Thesis.” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.), 236-246. Routledge.

Ciasullo, Ann M. “Making Her (In)visible: Cultural Representations of Lesbianism and the Lesbian Body in the 1990s.” Feminist Studies 27, no. 3 (2001): 577+.

Davis, Fred. “Do Clothes Speak? What Makes them Fashion?” Fashion Theory: A Reader (Malcolm Barnard, ed.), (2020): 225-235. Routledge.

Entwistle, Joanne. “Fashion and the Fleshy Body: Dress and Embodied Practice.” Fashion Theory 4, no. 3 (2000): 323-347.

Entwistle, Joanne. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress, and Modern Social Theory (2nd ed.), (2015): Polity Press.

Geczy, Adam, and Vicki Karaminas. Queer Style, (2013): Bloomsbury.

Genter, Alix. “Appearances can be Deceiving: Butch-Femme Fashion and Queer Legibility in New York City, 1945-1969.” Feminist Studies 42, no. 3 (2016): 604+.

Hall, Trish. “Piercing Fad is Turning Convention on Its Ear.” The New York Times (1991, May 19): https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/19/news/piercing-fad-is-turning-convention-on-its-ear.html.

Hamilton, Laura T., et al. “Hegemonic Femininities and Intersectional Domination.” Sociological Theory 37, no. 4 (2019): 315-341.

Hannon, Sharon M. Punks: A Guide to an American Subculture. (2010): GreenwoodPress.

Heinz, Rick. “Why Do We Use Dice in Tabletop RPGs?” Nerdist, (2019, April 11): https://nerdist.com/article/dice-tabletop-game-masters-hall-sponsored/.

Hess, Martine Aamodt. “Cottagecore, Frogs and Lesbian Earrings: A Celebration of Queer Trends.” Diva (2021, July): 20-21.

Kelly, Kim. “How the French Revolution Is Inspiring Today’s Online Anti-capitalists.” TeenVogue (2019, November 26): https://www.teenvogue.com/story/eat-the-rich-guillotine-anti-capitalists.

Laham, Martha. Made Up: How the Beauty Industry Manipulates Consumers, Preys on Women's Insecurities, and Promotes Unattainable Beauty Standards. (2020): Rowman & Littlefield.

“Lesbian Earrings.” Google Trends. [Accessed April 4, 2025]. (n.d.): https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=lesbian%20earrings&hl=en-US.

Lenzen, Cecilia. “TikTok Lesbians will make Earrings out of Literally Anything.” dailydot (2020, September 23): https://www.dailydot.com/irl/lesbian-earrings-tiktok/.

“LGBTQ+ Symbols & Meanings.” De Montfort University Leicester. (n.d.) [Accessed July 3, 2023]: https://www.dmu.ac.uk/events/pride/symbols.aspx.

Mak, Geertjie. “Sandor/Sarolta Vay: From Passing Woman to Sexual Invert.” Journal of Women’s History 16, no. 1 (2004): 54-77.

McKee, Heidi A., and James E. Porter. “Rhetorica Online: Feminist Research Practices in Cyberspace.” Rhetorica in Motion: Feminist Rhetorical Methods & Methodologies, (Eileen E. Schell and K.J. Rawson, eds.), (2010): 152-170. University of Pittsburgh Press.

Nadège. “The Sex Act You’ve Never Heard Of That’s Haunted Queer Women for Centuries.” Medium (2020, June 8): https://medium.com/pleasure-science/the-sex-act-youve-never-heard-of-that-s-haunted-queer-women-for-centuries-2439301f7af9.

Prager, Sarah. “Lesbian Earrings are Taking Over TikTok, and They’re Wild.” them (2020, September 18): https://www.them.us/story/tiktok-lesbian-earrings.

“Prohibited Items Policy.” Etsy (2023, June 5) [Accessed July 3, 2023]: https://www.etsy.com/ca/legal/prohibited#Q7.

Recuber, Timothy. “Digital Discourse Analysis: Finding Meaning in Small Online Spaces.” Digital Sociologies, (Jessie Daniels, Karen Gregory and Tressie McMillan Cottom, eds.) (2017): 47-60.

Schiaparelli, Elsa. “Hat.” The Met (n.d.) [Accessed July 30, 2023]: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/83437.

Schöb, Mia and Henri Myrttinen. “Men and Masculinities in Gender Responsive Small Arms Control.” Gender Equality Network for Small Arms Control (2022, March): https://gensac.network/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Men-and-Masculinities_final.pdf.

Siclait, Aryelle, and Naydeline Mejia. “The History and Meaning of The Lesbian Pride Flag Is Nuanced And Ever-Evolving.” Women’s Health (2022, June 22): https://www.womenshealthmag.com/life/a36523338/lesbian-pride-flag-meaning/.

Sklar, Monica, et al. “Fashion Cycles of Punks and the Mainstream: A US Based Study of Symbols and Silhouettes.” Fashion Practice 13, no. 2 (2020): 253-274.

Sontag, Susan. Notes on ‘Camp’ [Essay]. (1964): https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag_Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf.

“The Life and Death of Femme Flagging.” Into (2023, October 16): https://www.intomore.com/culture/the-life-and-death-of-femmeflagging/.

Vänskä, Annamarie. “From Gay to Queer- Or, Wasn’t Fashion Always a Very Queer Thing?” Fashion Theory 18, no. 4 (2014): 447-463.

Whitten, Sarah. “Dungeons & Dragons had its Biggest Year Ever as Covid Forced the Game off Tables and onto the Web.” CNBC (2021, March 13): https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/13/dungeons-dragons-had-its-biggest-year-despite-the-coronavirus.html.

Wilber, Jennifer. “10 Things That Are Bisexual Culture.” Paired Life (2023, June 25): https://pairedlife.com/gender-sexuality/10-Things-that-are-Bisexual-Culture.

Author Bio

Lilly Compeau-Schomberg is a Second year MA Fashion student at Toronto Metropolitan University. She graduated from the University of Western Ontario in 2023 with a MA in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies. Her research interests include queer women’s fashion, fashion as identity communication, and critical analysis of gender and sexuality in fashion and costuming. Lilly is a recipient of the Ontario Graduate Scholarship for her 2023-2024 academic year. She presented at the Fashion Studies Network 2024 Symposium, “Unravelling Fashion Narratives,” and has given two guest lectures at the University of Western Ontario for the “Gender and Fashion” course.

Article Citation

Compeau-Schomberg, Lilly. “Things Being what they are Not: Contextualizing the “Lesbian Earring” Trend.” Unravelling Fashion Narratives, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-25. https://doi.org/10.38055/UFN050109.

Copyright © 2025 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)