Threads of Gold: Reclaiming the Textile in the Metaphors for Biblical Citations in Medieval Hebrew Literature

By Emma Cusson & Guadalupe González Diéguez

DOI: 10.38055/FCT040108

MLA: Cusson, Emma, and Guadalupe González Diéguez. "Threads of Gold: Reclaiming the Textile in the Metaphors for Biblical Citations in Medieval Hebrew Literature." Corpus Textile, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040108

APA: Cusson, E & González Diéguez, G. (2025). Threads of Gold: Reclaiming the Textile in the Metaphors for Biblical Citations in Medieval Hebrew Literature. Corpus Textile, special issue of Fashion Studies, 4(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040108

Chicago: Cusson, Emma, and Guadalupe González Diéguez. "Threads of Gold: Reclaiming the Textile in the Metaphors for Biblical Citations in Medieval Hebrew Literature." Corpus Textile, special issue of Fashion Studies 4, no. 1 (2025). 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040108

Special Issue Volume 4, Issue 1, Article 8

Keywords

Scriptural citations

Bible

Quran

Embroidery

Textile metaphors

Hebrew literature

Abstract

This paper traces the origin of the metaphor of the “mosaic” (šibbuṣ), commonly employed in Hebrew literary studies to refer to the practice of inserting biblical citations in literary texts, both religious and secular, which was widely practiced in the medieval period in Islamic Iberia (al-Andalus). Following up on the title of our conference, Fashioning and Breaking Bodies: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Sartorial Materiality, we will argue that the metaphoric language of the mosaic “breaks” the body of the biblical text, dividing it up in discrete fragments. In the footsteps of scholars of Hebrew literature, such as Neal Kozodoy and Peter Cole, we will propose reclaiming a different semantic field of metaphors, that of the embroidery (tašbeṣ). We point to examples in the medieval textile industries of the Islamic world that help us fashion differently, in a more flexible and continuous way, the practice of creative writing by means of the interweaving of biblical citations. The ubiquity and cultural and economic importance of these textiles with embroidered inscriptions in the Islamic world in general, and in al-Andalus in particular, support our hypothesis that the medieval Hebrew poets were invoking them when they referred to the insertion of biblical citations in their writings.

Introduction

“The text is a tissue of quotations…”

Roland Barthes, “The Death of the Author” (1967)

The affinities between text and textile are already present in the very etymology of the word. The English term “text” is derived from the Latin textus, a perfect infinitive of the verb texo, meaning “to weave, to plait together.”

In what follows, we will trace the origin of a very different metaphor commonly employed in Hebrew literary studies, that of the “mosaic” (šibbuṣ), to refer to the practice of inserting biblical citations in literary texts, both religious and secular, which was widely practiced in the medieval period in Islamic Iberia (al-Andalus). Following up on the title of our conference, Fashioning and Breaking Bodies, we will argue that the metaphoric language of the mosaic “breaks” the body of the biblical text, dividing it up in discrete fragments. In the footsteps of scholars of Hebrew literature such as Neal Kozodoy and Peter Cole, we will propose reclaiming for this purpose textile metaphors, more specifically the embroidery (tašbeṣ), pointing at examples in the medieval textile industries of the Islamic world that were part and parcel of the cultural context in which Hebrew writers in the medieval Mediterranean interwove biblical citations in their writings.

During the medieval period, most of the world’s Jewish population lived as protected minorities (ḏimmis) under Muslim rule. Since the emergence of Islam in the seventh century C.E., and its subsequent expansion until the end of the thirteenth century, known as the end of the period that historians name the “High Middle Ages,” Jewish communities in the lands of Islam held not only the demographic, but also the cultural pre-eminence within Judaism.[1] These communities were fluent in the Arabic language, and they participated in the cultural enterprise of the Islamicate world.[2] They produced scientific and philosophical works in Arabic language, just like their Muslim counterparts did, adapting some of the literary models employed by the Arabic writers in their own works, composed both in Arabic and in Hebrew. Rina Drory has explained this process as the adoption of a literary system, initially implemented by Muslims, in which the Quran occupies the place of privilege not only religiously, as revealed Scripture, but also aesthetically. This system would be taken on by the Jewish authors, first Karaite, and then Rabbanite,[3] who would, in their case, put the Hebrew Bible at the center of their literary system:

From the tenth century onwards, the organizing principles of the Arabic

hierarchy of literary genres (with the Koran as its summit) is introduced into

Jewish literature, with such results as the configuration of new literary activities

around the Bible; the emergence of a new division of functions between the

written languages; and the adoption of new Arabic literary models in Jewish

literature, reshaping the repertoire of models for writing in Hebrew and in

Judeo-Arabic.[4]

As part of the Islamicate realm, the Jewish community of al-Andalus, the southern parts of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule,[5] participated in this cultural process. Andalusi Jews were fluent in Arabic and reached a relatively high level of cultural assimilation, making important contributions in Arabic language in different areas of knowledge, such as the natural sciences, philosophy, politics, philology, and the arts.[6] They also created a new kind of Hebrew poetry, following poetic models taken from the Arabic. Up until that moment, post-biblical Hebrew poetry had been exclusively religious and liturgical poetry (piyyuṭ).[7]

[1] Robert Chazan, The Jews of Medieval Western Christendom: 1000-1500 (Cambridge University Press, 2006), 3–5.

[2] We use the term “Islamicate,” coined by Marshall Hodgson, to refer “not directly to the religion, Islam, itself, but to the social and cultural complex historically associated with Islam and the Muslims, both among Muslims themselves and even when found among non-Muslims.” Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam (University of Chicago Press, 1974) vol. I, 59.

[3] Karaite and Rabbanite refer to two different currents, or what we may call “denominations,” within medieval Judaism. Karaism is “a Jewish religious movement of a scripturalist and messianic nature, which crystallized in the second half of the ninth century in the areas of Persia-Iraq and Palestine,” see Moira Polliack, Karaite Judaism (Brill, 2003), XVII. It flourished between the ninth and the eleventh centuries c.e., and its main feature was the rejection of the authority of the Oral Law. Rabbanite, or rabbinical Judaism, which became the dominant, standard form of Judaism as we know it today, was centered, on the contrary on the study and authority of the Oral Law.

[4] Rina Drory, Models and Contacts: Arabic Literature and Its Impact on Medieval Jewish Culture (Brill, 2000), 7.

[5] Significant parts of the Iberian Peninsula were under Muslim rule during the Middle Ages, between 711 c.e. and 1492 c.e. This area was known as “al-Andalus” in Arabic; whereas the Jews employ the term “Sepharad” to refer to the Iberian Peninsula. The territories ruled by Muslims decreased notably starting in the thirteenth century, and by the fifteenth century they were reduced to the single kingdom of Granada, in the southern tip of the Peninsula.

[6] Esperanza Alfonso, Islamic Culture Through Jewish Eyes: Al-Andalus from the Tenth to Twelfth Century (Routledge, 2008).

[7] Liturgical poetry (piyyuṭ) probably originated in 1st century c.e. Palestine to embellish the service in the synagogue, and it evolved over time from a simpler and less ornate style into a much more obscure and enigmatic expression, using neologisms, rare words, and midrashic allusions. The poems of piyyuṭ are rhymed, usually divided in strophes, and they employ a Hebrew that is described as midway between biblical and rabbinic. See Ángel Sáenz-Badillos, A History of the Hebrew Language (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 209–214.

These advances gave rise to new poetic forms that developed both religious and, as a radical innovation, secular topics (for example, love poems, poems dedicated to wine, praise poems, etc.). Similar to what Arabic poets did with the Quran, Andalusian Jewish authors looked back at the language of the Bible as the standard for their literary creation, and took up the vocabulary and expressions of biblical Hebrew, a language which had not been used creatively and productively for centuries in secular writing.

Biblical Citations as Adornment of Poetry According to Moses ibn Ezra

We can read a first-hand description of this process in the words of one of the major Hebrew poets from this period, Moses ibn Ezra (ca. 1055-after 1135), who also composed (in Arabic) the first known treatise of Hebrew literary criticism, the Book of Discussion and Remembrance (Kitāb al-muḥāḍara wa’l-muḏākara). Moses ibn Ezra was born into an influential family from Granada. He was trained at the rabbinical academy of Lucena, under the mentorship of Isaac ibn Ghiyyat. He became a courtesan poet and led an itinerant life in the Muslim kingdoms of the south of Iberia. After the invasion of al-Andalus by the north African dynasty of the Almoravids in 1090, he decided to flee north into the Christian kingdoms. He would spend the last part of his life in the Christian lands, where his poetry was shaped by the topics of exile and solitude. Among his works, he left an important poetic production (diwān) of more than 400 poems, both secular and religious, his abovementioned treatise of Hebrew literary criticism, and a philosophical-exegetical work of Neoplatonic style, Treatise of the Garden of Figurative and Literal Meaning (Maqālat al-ḥadīqa fī maʿana al-majāz wa’l-ḥaqīqa).[8]

Ibn Ezra openly explains the purpose of his treatise on Hebrew literary criticism as follows:

These pages of little content aim to explain to you the question of how the two

nations, i.e., the Hebrew and the Arabic, are, and their parallelism in most

aspects, since the first one imitates the second, and takes from it, particularly in

what regards to poetry.[9]

In Arabic, this literary device is called “ignition” (iqtibās), referring to the action of “taking a burning coal or a brand (qabas) from a fire to light something else.”[10] The Quranic expression is compared to a lit coal which transfers luminosity and splendor to the text into which it is inserted. Quranic language was not always cited in pious or reverential manner; authors also used it in neutral manner, and for shock value in unexpected, or openly subversive contexts, constituting what Geert van Gelders has aptly named “forbidden firebrands.”[11]

[8] For an overview of his life and work, see Ángel Sáenz-Badillos and Judit Targarona Borrás, Diccionario de autores judíos. Sefarad. Siglos X-XV (Ediciones El Almendro, 1988), 69. In English, see Peter Cole, The Dream of the Poem. Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492 (Princeton University Press, 2007), 121–122.

[9] Moshe ibn Ezra, Kitāb al-muḥāḍara wa’l-muḏākara, ed. Montserrat Abumalhan Mas (CSIC, 1985), vol. 1, fol. 6v. Translation into English is ours.

[10] Bilal Orfali, “Iqtibās,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three, ed. Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Devin J. Stewart (Brill, 2007). Consulted online on 19 February 2023. The root is employed in Q 57:13 with the sense of enlightening, conveying luminosity.

[11] Geert van Gelder, “Forbidden firebrands. Frivolous iqtibās (quotation from the Qurʾān) according to medieval Arab critics,” Quaderni di studi arabi 20/1 (2002–03), 3–16.

Moses ibn Ezra includes at the end of his treatise on poetics a list of twenty rhetorical devices employed to beautify poetry (maḥāsin al-šiʿr), such as metaphor, hyperbole, etc. After this list, he includes a section on “proverbs (amṯāl) and enigmas (aḥāji),” within which he discusses the insertion of Scriptural verses or sections of verses. Scriptural citations would constitute a kind of riddle, an enigma, because the knowledgeable reader would be able to recognize and identify them. Ibn Ezra does not, however, employ the term iqtibās to refer to this device. He says:

The Arab poets found it laudable to introduce verses from their Qurʾān what they

call āyāt or “wonders” in their poetry, and in their eyes, these belong to their

glorious sayings. Most of them appear in the first hemistich (always at the

beginning of the poem), as one of them [of the Arab poets] said: “Spoke the

musk by his gates [saying]: / Enter ye here in Peace and Security” (Qurʾān 15:46).[12]

[…] It has been possible for the poets of our community to do something similar,

with complete verses and with part of them, introducing them into the hemistiches

of various sizes, [sometimes] with small additions, [sometimes] with some

deletions, and [sometimes] without any [modification]. Most of them are taken

from the compositions of Psalms, Job and Proverbs […].

The Arab poets have curiosities in verses, with figures of meaning taken from

their Qurʾān and only from them can they be imitated, for example what one

said about thinness: “If my thinness was transferred onto a camel, / nobody

would ever stay in hell. Because their Qurʾān says: “No opening will there be of the

gates of heaven, nor will they [the wicked] enter the Garden, until the camel can

pass through the eye of the needle (Qurʾān 7:40).” […] Among our compatriots [i.e.

the Jews] there are those who have imitated this way, composing verses with

figures whose meaning is taken from sacred books; there are those who completed

their endeavor in one verse and those who used two.[13]

[12] For the identification of the author of this verse, see Noah Braun, “The Arabic Verses,” Tarbiz 14 (1943): 200 (# 71) [Hebrew].

[13] Ibn Ezra, Kitāb, fols. 154v–156r. Translation into English is ours. An alternate English version of the text is also provided in Arie Schippers, “Biblical and Koranic Quotations in Hebrew and Arabic Andalusian Poetry,” in ‘Ever’ and ‘Arav,’ Contacts between Arabic Literature and Jewish Literature in the Middle Ages and Modern Times, ed. Yosef Tobi (Afikim, 2001) vol. 2, 9–22.

It can be argued that the insertion of biblical citations existed in Hebrew literature well before any contacts with the Arabic literary system; in fact, the Hebrew Bible practices the biblical citation of earlier passages within its own corpus. Michael Fishbane has famously referred to “inner biblical exegesis,” and one could, by analogy, speak of “inner biblical citation.”[14] The authors of classical piyyuṭ and the rabbis also included biblical expressions and citations in their works. David Yellin notes that the classical liturgical poets, such as Yosi ben Yosi and Eliezer ha-Kallir, employed fragments of Scriptural verses sparingly, and, for the most part, in a fixed place at the end of the rhymes in their poems.[15]

A more radical critique of the very possibility of biblical citation within the corpus of medieval Hebrew poetry is offered by Schippers in an article that compares biblical and Quranic quotations in Hebrew and Arabic Andalusian poetry. Schippers notes that Ibn Ezra does not offer any examples of literal citations from the Bible in Hebrew poetry, and he deduces that this is because for Ibn Ezra, as well as for his contemporaries, “the whole corpus of the poetry of the Hebrew Andalusian school consists by definition of the Holy language,” that is, biblical Hebrew. It becomes thus impossible to ascertain “why a certain phrase of Hebrew poetry rather than others should be considered a quotation: all are of biblical origin. Everything about this poetry is biblical, so no striking feature, no additional effect, can be singled out such as, in Arabic poetry, the occurrence of a Koranic phrase.”[16] Only later, after having lost awareness of this biblical substratum of the whole of medieval Hebrew poetry, did it become possible to distinguish in the medieval Hebrew poems between biblical “quotation” (which would later become what us readers recognize as a biblical quotation) and that which is not (recognized by us as) biblical quotation.

Schippers’ critique does certainly have a point, and scholars have tried to circumvent this impossibility to discern what would constitute in this context a biblical quotation. One possible criterion is qualitative, and sometimes the technique of biblical citation is defined, for instance, as “at least three biblical words, not necessarily in the order in which they appear in Scripture.”[17] The criterion could also be qualitative, as for instance in the case of heavily connoted terms, or hapax legomena that are intrinsically associated with certain biblical episodes.

[14] Michael Fishbane, “Inner Biblical Exegesis: Types and Strategies of Interpretation in Ancient Israel,” in Midrash and Literature, ed. Geoffrey Hartman and Sanford Budick (Yale University Press, 1986) 19–37. Verses or fragments of verses from the Torah are cited in the sections of the Prophets and the Writings in the Hebrew Bible, for example, numerous verses from Genesis are reprised in the Psalms. See also Jean-Jacques Lavoie, “L’Écriture interprétée par elle-même,” in Entendre la voix du Dieu vivant: interprétations et pratiques actuelles de la Bible, ed. Jean Duhaime and Odette Mainville (Médiaspaul, 1994), 83–95.

[15] David Yellin, Theory of Spanish Poetry (Jerusalem, 1940, 2nd ed. 1972), 119 [Hebrew].

[16] Schippers, “Biblical and Koranic Quotations in Hebrew and Arabic Andalusian Poetry,” 22.

[17] Peter Cole, The Dream of the Poem. Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492 (Princeton University Press, 2007), 542.

Himself an accomplished poet, Moses ibn Ezra employed this technique, of which we can see a paradigmatic example in his famous poem “The Garden,” which plays with the insertion of multiple biblical citations referring to clothes to describe the colours and textures of a garden in spring:

The garden wears a colored coat,[18]

The dress of the lawn[19] are embroidered robes,

The trees are wearing checkered shifts,[20]

They show their wonders to every eye,

And every bud renewed by spring

Comes smiling forth to greet his lord.

See! Before them marches a rose,

Kingly, his throne above them borne,

Freed of the leaves that had guarded him,

No more to wear his prison clothes.[21]

Who will refuse to toast him there?

Such a man his sin will bear.[22]

It may well be, as Schippers argues, that each one of the words in this poem can be found in the biblical corpus, but we do recognize certain phrases, in this case made up of two words, that have a particular resonance and that evoke specific objects or events in the biblical account. We would argue that this holds for us, contemporary readers, as well as for our medieval counterparts: for instance, the “colored coat” of the first line carries an intensity that is not found in more anodyne expressions that could also be taken from the Bible, like “such a man.”

[18] Literally “multicolored coats,” (kotnot passim) in the plural. This biblical expression refers to the famous multicolored tunic of Joseph (Gen 37: 3), as well as to that of Tamar (II Samuel 13: 18–19).

[19] The “dresses” (midde) of the lawn refers to the dress of linen worn by the priest in preparation before offering a sacrifice in Lev 6:3.

[20] “Checkered shift” is taken from “checkered shift and tunic” (meʿil u-ḵtonet tašbeṣ) in the description of the apparel of the High Priest in Exod 28:4.

[21] “His prison clothes” (bigde kil’o), expression used in II Kings 25:27–30, to refer to king Jehoiakim of Judah, who had been imprisoned in Babylon for 37 years, and finally was liberated under the successor of Nebuchadnezzar.

[22] This echoes Numbers 9:13, with a slight inversion in the order of the words. We cite the English translation by Raymond Scheindlin, Wine, Women and Death. Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life (The Jewish Publication Society, 1986), 35.

Here, in this version the “checkered shifts” translate the biblical term tašbeṣ (“chequered (or plaited) cloth”), from the root š-b-ṣ. According to the The New Brown, Driver, and Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, this root in its verbal forms means probably “to weave in chequer or plaited work.”[23] We also find in the Bible the related nominal form mišbeṣot (“chequered (or plaited) work, usually of settings for gems”).

The intensive use of this technique started with the Jewish poets of medieval Sepharad, and it later crossed over to Hebrew rhymed prose. The technique evolved by enchaining citations of verses or fragments of verses one after the other, sometimes producing compositions that are almost entirely made up of “cut and paste” fragments of biblical text; and of tweaking the biblical citations “[sometimes] with small additions, [sometimes] with some deletions, and [sometimes] without any [modification],” in the words of Moses ibn Ezra.

Despite its widespread use, this technique did not receive a specific name in Hebrew, although sometimes it was referred to as meliṣah, a general way to name ornate or stylized language. As we will see in the following section, it would be called by the name of “Mosaic style” (in German) in mid-nineteenth century Europe. Roughly one century later, the German term would be translated into Hebrew as šibbuṣ, a word from the same root as tašbeṣ, but with a different semantic field of connotations, far from the textile, which would become the standard name for this literary device.

[23] Brown, Francis, S.R. Driver and Charles A. Briggs, The New Brown, Driver, and Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (Associated Publishers and Authors Inc., [1907] 1981), 990.

The “Mosaic Style” of Biblical Citation in Nineteenth-Century German Scholarship

The Romantic period sparked the interest of European scholars in the Bible as literature, as we can see for instance in the works of the German philosopher Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803), who composed a book on The Spirit of Hebrew Poetry (1782-3). In it, he says the following about what he calls the “playful” insertion of biblical citations in Hebrew poetry:

Among the Hebrews, history and poetry rest in a great measure on paronomasia

[wordplay], as on the originals of the language, and only by a taste for these

can our ear come to an intimate acquaintance with the spirit of the language.

And this acquaintance is the more necessary, since their writers delight in copying

and improving upon each other in whole phrases, which they unfold and amplify,

each in his own peculiar style. This, too, if any chose to call it so, is a playing upon

words, yet such as even the refined Greeks would not dislike. It was a favorite

practice with them to express their own thoughts in the word of Homer and

other distinguished ancient writers; and who would not be gratified by it? Both the

speaker and hearer are gratified, the former with the successful exercise of his

invention, the latter with finding a new friend [making a new discovery] in

an old and favorite costume (Ausdruck), a new thought in a known and approved

form of expression. So the Prophets employ the figurative language of the

Patriarchal benedictions and the Psalms. So the modern Hebrews employ the

words of all the more ancient writers in a new sense, but in the same beautiful

forms of expression. Their poetical language, in employing the expression of the

Bible, may be said, perhaps, in some sense, to be nothing but a play upon words;

but how refined! How interesting for one, who has a taste for the simplicity

of ancient times, which in this way reappear, as it were, dressed in a finer

costume (Schmuck).[24]Writing a few decades after Herder, the Lutheran theologian and Hebraist Frantz Delitzsch (1813-1890)[25] will be the first to describe the technique of biblical insertions as Musivstyl, or “mosaic style,” in his On the History of the Jewish Poetry from the Closing of the Old Testament of the Holy Scripture and Up Until the Most Recent Times (1836). There, he recognizes the novelty of the denomination “mosaic style”:

Mosaic style, mosaic, emblematic style are newly coined speech images (neugeprägte

Redebilder) to describe one of the basic tones in the Orientalism and Romanticism

of Jewish poetry of the Middle Ages. An old Italian poet already transfers the

image of musical work to the style, the words of his distich are the most beautiful

miniature of that Jewish emblematics, about which only Herder, as far as I know,

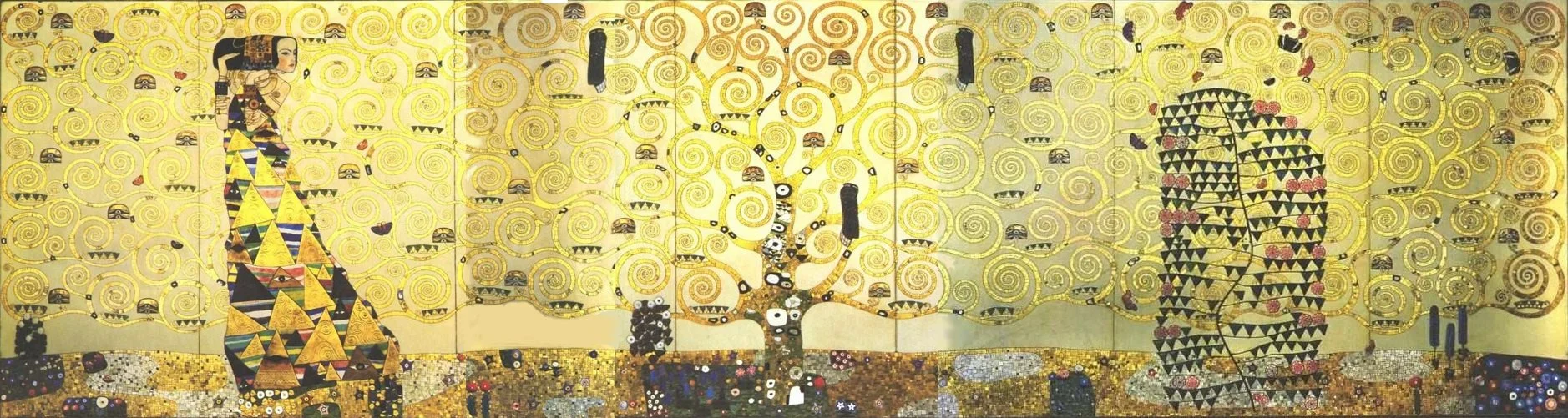

gave some dark but deeply thought-out hints.[26]The German Musiv originates in the Latin musivus, in turn derived from the Greek mousaios (that is, artistic, related to the Muses). A mosaic would be in Latin musivum. In German, it is not a very used term, and it evokes the Musivgold (also known by the rather problematic term Judengold), the fake gold-like metal that was employed in Byzantine mosaics, for instance, or in some works by Gustav Klimt (the golden mosaics of his Stoclet Frieze from 1905-1911).

[24] Johann Gottfried von Herder, Vom Geist der Ebraischen Poesie (Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1825), 281. The English version is taken from The Spirit of Hebrew Poetry, trans. James Marsh (Edward Smith, 1833), vol. 2, 214–215. Bold letters are ours. We have amended the rather free translation of “finding a new friend” into the more literal “making a new discovery”.

[25] Frantz Delitzsch was a German Lutheran with unusual knowledge of Hebrew and the rabbinic tradition, and who was, precisely for that reason, suspected of having Jewish ancestry. He is mostly known for this translation of the New Testament into Hebrew (1877), which he made with the goal of proselytizing among the Jews.

[26] Franz Delitzsch, Zur Geschichte der jüdischen Poësie vom Abschluss der heiligen Schriften Altes Bundes bis auf die neueste Zeit (Karl Tauchnitz, 1836), 164.

Figure 1

Gustav Klimt, "Stoclet Frieze" (1905-1911), left panel (Public Domain). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoclet_Frieze

The luminous effect evoked by this fake gold-like metal in German (or, at least, in nineteenth-century German) is lost to the contemporary English reader, the connotation of “mosaic” is most immediately the composition of an image out of little discrete pieces of stone or clay, the tesserae.

Soon after Delitzsch, the Hungarian-Jewish critic of Hebrew literature Leopold Dukes (1810-1891), in his work On the New Hebrew Religious Poetry (1842), includes a section on the history of the Musivstyl:

The art of the new Hebrew [literary] stylists dressing their thoughts into a

tissue of Bible citations (ihre Gedanke in ein Gewebe von Bibelstellen einzukleiden)

is referred to as the mosaic style (Musivstyl), because it can be compared to the

artful visual work of the mosaic, in which countless unequal pieces combine

into a beautiful whole. This expression was chosen because none was better

and more significant, and also because there was also no such expression in

Hebrew itself. This type of style had long existed even before it was mentioned

by a theorist, and also before it had received a specific name.[28]

The German term Musivstyl was later on translated into Hebrew as šibbuṣ. It seems that this translation was coined by David Yellin in his 1940 Hebrew book Theory of Spanish Poetry, as Neal Kozodoy already indicated in 1977.[29] Yellin says: “And in Hebrew, this is called by the name of šibbuṣ,” adding in a footnote that: “in the European languages this is called ‘the style of the mosaic’ (ha-signon ha-musivi), a name derived from the word ‘Mosaik’ (ʿuvdat pispasim).”[30] The term šibbuṣ is not employed in the Bible; it does appear in the Mishnah and Talmud, and in the religious poetry of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages (piyyuṭ).

[27] Delitzsch, Zur Geschichte, 167.

[28] Leopold Dukes, Zur Kenntnis der neuhebräeischen religiösen Poesie (Bach, 1842), 116. Translation into English is ours.

[29] Neal Kozodoy, “Reading Medieval Hebrew Love Poetry,” AJS Review 2 (1977): 111–129, 118, footnote 13.

[30] Yellin, Theory, 120 (body of the text and footnote 1). Translation into English is ours.

The term is most often translated into English (as well as into the other Western European languages) as “mosaic” or “inlay.” This metaphor creates a hard, fragmentary impression, and that fails to account for the luminosity that is conveyed by the gold, and the flexible integration that is conveyed by the textile. Writing in 1976, Hebrew literature scholar Dan Pagis employs abundant textile metaphors to explain the device that he calls “mosaic style,” but without calling into question the term itself:

In the period of classical piyyut, in general the verses of the Bible were not

integrated in the internal tapestry (riqmah) of the poem, but they were in fixed

places, for instance at the end of the rhymes. [But] already in the first poets

of Sepharad, we find an internal biblical interweaving (šĕzirah), and there are

poems whose internal tapestry is made fundamentally out of the warp and woof

(šĕti wa-ʿerev) of verses [taken] from different passages in the Bible.[31]

Where Pagis did not openly challenge the use of the “mosaic” metaphor, other scholars did. In a 1977 article, Neal Kozodoy explained in detail the inadequacy of this metaphor, and proposed a different metaphorical language:

The art of inlay is inadequate as an analogy to this method, which needs to be

seen as a more delicate and pliable operation. With greater accuracy we might

think of the poem as a garment woven with great skill from costly and colorful

material. Into this fabric have been twined threads of pure gold, beaten down

from a single golden bar, the Bible; … [These threads] call attention to

themselves, first, inviting us to hold up the work, tilting it at a variety of angles

and planes in an attempt to perceive whether they might not form some hidden

pattern. At the same time, they impart real depth and brilliance to the surfaces

surrounding them, and as we study these surfaces we become struck by the

impression of motion, as the presence of the pure gold subtly alters the values

and intensities of the surrounding hues.[32]

Similarly, Peter Cole noted:

The term itself is somewhat misleading and in fact reflects a development in

nineteenth-century German scholarship. […] The Hebrew term shibbutz means

“setting” or “inlay,” as in the craft of the jeweler or mosaicist, and relies on a

metaphor that misses the dynamic action of the scriptural force in the poem.[33]

[31] Dan Pagis, Innovation and Tradition in Secular Hebrew Poetry: Sepharad and Italy (Keter, 1976), 70 [Hebrew]. Translation into English is ours.

[32] Kozodoy, “Reading Medieval Hebrew Love Poetry,” 120.

[33] Cole, The Dream of the Poem, 542–543.

Following in the footsteps of Kozodoy and Cole, we would like to propose a different metaphor to think about the technique of biblical citation in medieval Hebrew literature. We recover a biblical term embedded into the abovementioned poem by Moses ibn Ezra: tašbeṣ, which we would render by tapestry or embroidery.

Text Written with Threads of Gold: Material Convergence of Text and Textile

In the printed booklet of the 2018 exhibition titled “Text and Textile,” held at the Beinecke Library in Yale University, curator Melina Moe reminds us that while “textiles are supple materials for fashioning figures of speech, […] textiles are also material, the product of global supply chains, complex machinery and backbreaking labor […]

This reminder led us to search for the “sartorial materiality” that could correlate to our metaphor of text embroidered with gold (or light).

During the period of Islamic rule in al-Andalus, changes in the agricultural techniques brought about what some scholars have even called a “green revolution.”[35] The introduction into the region of new crops, some of them of Indian provenance, the implementation of innovative irrigation techniques, and of schemes of crop rotation that allowed more than one harvest per year, as opposed to the traditional Mediterranean yearly harvest. These implementations significantly increased agricultural productivity, boosting both the economy and demography. Among the plants that were introduced, besides many edible crops, were species that fulfilled diverse industrial purposes, including textiles such as cotton, and mulberry trees for silk production.[36] The textile industry in al-Andalus, whose products were exported throughout the Islamic world, is often cited in studies as one of the main sources of revenue for the region.[37]

[34] Melina Moe, “Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs & the Finest Thread,” in Text & Textile (exhibition booklet), ed. Kathryn James, Melina Moe & Katie Trumpener (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, 2018), 15 and 18.

[35] Andrew Watson, Agricultural Innovation in the Early Islamic World (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[36] Vincent Lagardère, “Mûrier et culture de la soie en Andalus au Moyen Âge (Xe–XIVe siècles),” Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez. Antiquité et Moyen-Age, 26.1 (1990), 97–111.

[37] Maurice Lombard, Textiles in the Muslim World VIIe-XIIe siècle (Mouton, 1978).

As an important part of the decorative arts, luxury textiles were produced, such as silk tissue embroidered with gold thread. In al-Andalus, the manufacture of luxury textiles was introduced by the emir ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II (r. 822-852), who established in Cordoba the royal dār al-ṭirāz (“luxury textile factory”).

Writing in 1377 in North Africa, the historian Ibn Khaldūn explains this practice as follows:

It is part of royal and governmental pomp and dynastic custom to have the names

of rulers or their peculiar marks embroidered on the silk, brocade, or pure silk

garments that are prepared for their wearing. The writing is brought out by weaving

a gold thread or some other coloured thread of a colour different from that of the

fabric itself into it. (Its execution) depends upon the skill of the weavers in designing

and weaving it. Royal garments are embroidered with such a ṭirāz, in order to increase

the prestige of the ruler or the person of lower rank who wears such a garment, or

in order to increase the prestige of those whom the ruler distinguishes by bestowing

upon them his own garment when he wants to honour them or appoint them to

one of the offices of the dynasty. The pre-Islamic non-Arab rulers used to make a

ṭirāz of pictures and figures of kings, or figures and pictures specifically (designed)

for it. The Muslim rulers later on changed that and had their own names embroidered

together with other words of good omen or prayer. In the Umayyad and ‘Abbâsid

dynasties, the ṭirāz was one of the most splendid things and honours.[39]

[38] Yedida Stillman, Paula Sanders, and Nasser Rabbat, “Ṭirāz,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, ed. Peri Bearman, Thierry Bianquis, Edmund Bosworth et al. (Brill, 2000), vol. 10, 534–538.

[39] Ibn Khaldūn, The Muqaddimah. An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, ed. N. J. Dawood (Princeton University Press, 1967, 2005), 341–343.

We have a good number of references to textiles with embroidered inscriptions as a mark of prestige in al-Andalus, particularly those employed by the ruling Umayyad caliphs. For instance, caliph ʿAbd al-Raḥmān III (890-961) received a gift in 939 which contained garments embroidered with gold thread.[40] Another fascinating example of a vestment blending text and textile is the veil of Hishām II, a caliph who lived in Cordoba (976-1013): on this piece, we find an inscription indicating its production location and its future wearer,[41] acting as tags do in our contemporary clothing. Perhaps the most famous reference to these garments with inscriptions concerns the Umayyad princess Wallāda bint al-Mustakfī (11th century), who is reported to have worn a tunic with the following verses embroidered across her shoulders:

Worthy am I, by God, of the highest, and

Proudly I walk, with head aloft.

My cheek I give to my lover and, to those who wish them,

I yield my kisses.[42]

These adorned textiles produced in Islamic Iberia found their way into the northern Christian kingdoms, attesting to their prestige as high luxury items and to their economic value. They were distributed in a post-battle celebration in 997, when the Vizier Al-Mansour (978-1002) handed out textile gifts to warriors and Christian counts, which included eleven sets of silk garments embroidered with gold thread.[43] A ṭirāz produced in al-Andalus can be seen in the funeral trousseau of the Christian Queen Berenguela of Castile (m. 1246), preserved at the Monastery of Las Huelgas (Burgos), which contains three very richly decorated pillows of Muslim workmanship (from the late Almohad or early Nasrid period). The burgundy pillow, made of tapestry, carries two ṭirāz inscriptions around the central medallion and in the two upper and lower bands, which read “There is no God but God” (lā ilāha illā Allāh) around the medallion; and “the perfect blessing” (al-baraka al-kāmila) in the upper and lower bands.

[40] Eneko López-Marigorta, “How al-Andalus wrapped itself in a silk cocoon: the ṭirāz between Umayyad economic policy and Mediterranean trade,” Mediterranean Historical Review 38.1 (2023): 7.

[41] López-Marigorta, “How al-Andalus wrapped itself in a silk cocoon: the ṭirāz between Umayyad economic policy and Mediterranean trade,” 5.

[42] María Jesús Viguera, “Aṣluḥu li’l-maʿālī: On the Social Status of Andalusi Women,” in The Legacy of Muslim Spain, ed. Salma Khadra Jayyusi (Brill, 1992), 709.

[43] Juan José Larrea, “Du Tiraz de Cordoue aux montagnes du Nord. Le luxe en milieu rural dans l’Espagne chrétienne du haut Moyen Âge,” in Objets sans contrainte, ed. Laurent Feller and Ana Rodríguez (Publications de la Sorbonne, 2019), § 3. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.psorbonne.26793

In a similar example, the phrase “perfect blessing” in Kufic is read on an embroidered textile fragment named the “St Sernin’s chasuble” dating from the same period and woven in an Andalusian workshop.[44] Another vestment fragment (named “The Lion Strangler”) produced in the same period features lions and a Kufic inscription “prosperity.”[45]

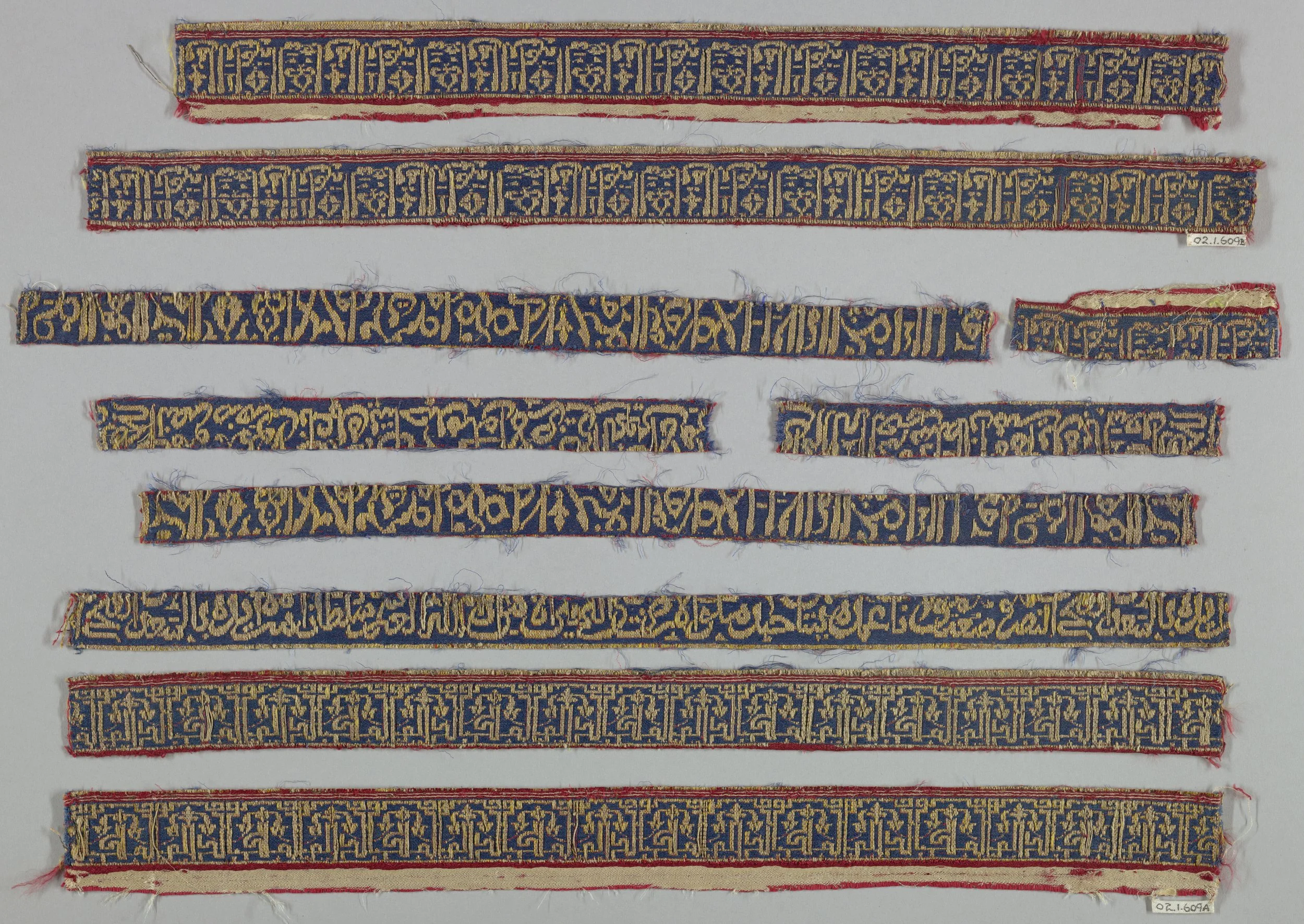

It is interesting for our purposes here to note that the inscriptions embroidered in the bands were often Quranic quotations or other religious formulas. The ornamental elements in the textile design presents marked similarities with Quranic ornamentation and book miniatures, according to Partearroyo.[46] We can observe these similarities in the image below:

Figure 3

Cooper Hewitt. Fragments of ṭirāz from 14th century Spain, silk and metallics, woven (Public domain). https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18131769/

Figure 2

Queen Berenguela's pillow, Monastery of Santa Maria la Real de las Huelgas, Burgos, Patrimonio Nacional, 00650512

The prevalence of textile metaphors in the titles of works dedicated to Arabic grammar, philology, and literature, disciplines heavily associated with Quranic interpretation, studied by Mesa Fernández,[47] also strengthens our hypothesis. The words of revelation were perceived as a precious embroidery in the Islamicate imagination.

[44] Musée de Cluny, “Fragment de la chasuble de saint Exupère.” https://www.musee-moyenage.fr/collection/oeuvre/chasuble-de-saint-exupere.html

[45] Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, “The Lion Strangler,” January 27, 2016, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2016/01/27/the-lion-strangler/

[46] Cristina Partearroyo, “Tejidos andalusíes,” Artigrama 22 (2007): 371–419, 372.

[47] Elisa Mesa Fernández, “Bordar las palabras: título y contenido en la literatura árabe clásica,” in Tejer y vestir de la antigüedad al islam, ed. Manuela Marín (CSIC, 2001), 219–238. Some examples, covering a long period of time, are The Embroidery of Literature (Ṭirāz al-adab), by Abū Firās, in the 10th century; The Embroidery that Includes All What is Needed to Discover the Secrets of Rhetoric and the Sciences of the Truths of [Quranic] Inimitability (Al-ṭirāz al-mutaḍammin li-asrār al-balāga wa-ʿulūm ḥaqā’iq al-iʿjāz), by the Yemeni Ibn Rasūl Allāh (14th century); to the more recent The Gold Embroidery on the Belt of Literature (Ṭirāz al-ḏahab ʿala wišaḥ al-adab), by Muhammad b. Aḥmad al-Muṭahhar al-Azdī (19th century).

As the above-cited passage from Ibn Khaldūn states, “a gold thread or some other coloured thread of a colour different from that of the fabric itself” was used in the ṭirāz.

In fact, in the discussion portion of the conference, Ersy Contogouris precisely argued that metal conveys hardness, and is thus not so different from the tesserae of the mosaic. How did then the artisans of the ṭirāz manage to bend the gold to be able to embroider with it? The gold thread (called ṣarma or “goldwork embroidery”) was elaborated by first preparing fine threads out of the membrane of the intestine of beef or lamb, which were gilded (that is, thinly covered with gold) and cut into very narrow strips. These were wrapped around a silk thread, which was the “core.” This type of thread was called by the Christians oropel (a portmanteau word meaning something like “gold-skin.”)[48] The funeral trousseau of Queen Berenguela contains another pillow with goldwork embroidery, which is shown in the images below:

Figure 4

Queen Berenguela's pillow, Monastery of Santa Maria la Real de las Huelgas, Burgos, Patrimonio Nacional, 00651964

Figure 5

Queen Berenguela's pillow, Monastery of Santa Maria la Real de las Huelgas, Burgos, Patrimonio Nacional, 00651964 (detail)

The amount of gold required for this manufacture was significant, and the domestic gold mines around the rivers Segre, Tajo and Darro in the Iberian Peninsula could not satisfy the demand. Therefore, gold was imported from Sub-Saharan Africa. This links our gold threads with the very material “development of trade routes, and the uneven accumulation of national wealth across the globe,”[49] echoing the words by Melina Moe cited at the opening of this section.

[48] Partearroyo, “Tejidos andalusíes,” 373. Translation into English is ours.

[49] Moe, “Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics,” 18.

Concluding Remarks

Our choices of metaphoric language are never neutral. In this paper, we have inquired about the origins of the metaphor of the mosaic to refer to the insertion of biblical citations in Hebrew literature. In the wake of other scholars, such as Kozodoy and Cole, we have proposed to replace it with a different kind of metaphor, from the textile semantic field, which conveys better the integrity, continuity, and suppleness of the textual body of Scripture, as opposed to the hard, discontinuous granularity of the mosaic. Going beyond previous scholars, we have researched in the material culture of medieval Iberia examples of the sartorial materiality that could have underpinned the metaphor of the gold embroidery. We have thus examined the agricultural innovations that were introduced, the development of a textile industry, and the establishment of highly specialized workshops of ṭirāz, providing several visual examples and literary references which attest to the popularity and ubiquity of gold embroidery in the Andalusi context. We have argued that the presence of these concrete objects shaped the imaginary of the Hebrew poets when they used the metaphor of embroidering words, often taken from sacred Scriptures, with gold thread. In this gold thread, which represents the luminosity and intensity of the words from Scripture, the metal is not cold and hard, but hot and malleable; it is like molting gold.

In the exercise of this fiber art, the thread must pass behind the fabric—it withdraws itself and is hidden from the eye—and it then reemerges while drawing unto itself the attention on the other side of the embroidered textile, adding a texture and a visual effect. The incorporation of biblical citations in the poem thus mimics the ornamented aspect of the gold thread that runs through the fabric.

References

Alfonso, Esperanza. Islamic Culture Through Jewish Eyes. Routledge, 2008.

Braun, Noah. “Arabic Verses in Kitāb al-muḥāḍara wa'l-muḏākara.” Tarbiz 14 (1943): 126–139; 191–203 [Hebrew].

Brown, Francis, S.R. Driver and Charles A. Briggs. The New Brown, Driver, and Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Associated Publishers and Authors Inc., [1907] 1981.

Cole, Peter. The Dream of the Poem. Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950-1492. Princeton University Press, 2007.

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. “The Lion Strangler.” Accessed September 3, 2025 https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2016/01/27/the-lion-strangler/

———. “Fragments of Tiraz (Spain).” Accessed August 6, 2025 https://collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18131769/

Decter, Jonathan. “Panegyric as Pedagogy: Moses ibn Ezra’s Didactic Poem on the ‘Beautiful Elements of Poetry’ (maḥāsin al-shir) in the Context of Classical Arabic Poetics.” In His Pen and Ink are a Powerful Mirror. Andalusi, Judaeo-Arabic, and Other Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Ross Brann, edited by Adam Bursi, S.J. Pearce, and Hamza Zafer. Brill, 2020.

Delitzsch, Frantz. Zur Geschichte der jüdischen Poësie vom Abschluss der heiligen Schriften Altes Bundes bis auf die neueste Zeit. Karl Tauchnitz, 1836.

Drory, Rina. Models and Contacts: Arabic Literature and Its Impact on Medieval Jewish Culture. Brill, 2000.

Drory, Rina. “Literary Contacts and Where to Find Them: On Arabic Literary Models in Medieval Jewish Literature.” Poetics Today 14, no. 2 (1993): 277–302.

Dukes, Leopold. Zur Kenntnis der neuhebräeischen religiösen Poesie. Bach, 1842.

Fishbane, Michael. “Inner Biblical Exegesis: Types and Strategies of Interpretation in Ancient Israel.” In Midrash and Literature, edited by Geoffrey Hartman and Sanford Budick. Yale University Press, 1986.

Gelder, Geert van. “Forbidden firebrands. Frivolous iqtibās (quotation from the Qurʾān) according to medieval Arab critics.” Quaderni di studi arabi 20, no. 1 (2002–3), 3–16.

Herder, Johann Gottfried von. Von Geist der ebräischen Poesie. Verlagskasse Buchhandlung der Gelehrte, 1782.

Hodgson, Marshall. The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Ibn Ezra, Moses. Kitāb al-muḥāḍara wa'l-muḏākara. Edited by Montserrat Abumalhan Mas. CSIC, 1985.

Kozodoy, Neal. “Reading Medieval Hebrew Love Poetry.” AJS Review 2 (1977): 111–129.

Lagardère, Vincent. “Mûrier et culture de la soie en Andalus au Moyen Age (Xe–XIVe siècles.” Mélanges de la Casa de Velázquez. Antiquité et Moyen-Age 26, no. 1 (1990), 97–111.

Larrea, Juan José. “Du tiraz de Cordoue aux montagnes du Nord. Le luxe en milieu rural dans l’Espagne chrétienne du haut Moyen Âge.” In Objets sous contrainte. Circulation de richesses et valeur des choses au Moyen Âge. Edited by Laurent Feller and Ana Rodríguez. Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.psorbonne.26793

Lavoie, Jean-Jacques. “L’Écriture interprétée par elle-même.” In Entendre la voix du Dieu vivant: interprétations et pratiques actuelles de la Bible. Edited by Jean Duhaime and Odette Mainville. Médiaspaul, 1994.

Lombard, Maurice. Les textiles dans le monde musulman di VIIe au XIIe siècles. Mouton, 1974.

López-Marigorta, Eneko. “How al-Andalus wrapped itself in a silk cocoon: the ṭirāz between Umayyad economic policy and Mediterranean trade.” Mediterranean Historical Review 38.1 (2023): 1–23.

Marín, Manuela, ed. Tejer y vestir de la antigüedad al Islam. CSIC, 2001.

Mesa Fernández, Elisa. “Bordar las palabras: título y contenido en la literatura árabe clásica.” In Tejer y vestir de la antigüedad al islam. Edited by Manuela Marín. CSIC, 2001).

Moe, Melina. “Tight Braids, Tough Fabrics, Delicate Webs & the Finest Thread.” In Text & Textile (exhibition booklet). Edited by Kathryn James, Melina Moe, and Katie Trumpener. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, 2018.

Musée de Cluny. “Fragment de la chasuble de saint Exupère.” Accessed October 20, 2026. https://www.musee-moyenage.fr/collection/oeuvre/chasuble-de-saintexupere.html

Orfali, Bilal. “Iqtibās.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, et al. Brill, 2007- [Consulted online on 19 February 2023].

Owen-Crocker, Gale et al., eds. Textiles of Medieval Iberia. Cambridge University Press, 2022.

Pagis, Dan. Innovation and Tradition in Secular Hebrew Poetry: Sepharad and Italy. Keter, 1976 [Hebrew].

Partearroyo, Cristina. “Almoravid and Almohad Textiles.” In Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. Edited by Jerrilyn Dodds. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992.

Partearroyo, Cristina. “Tejidos andalusíes.” Artigrama 22 (2007): 371–419.

Patrimonio Nacional. “Almohada de la reina Berenguela.” Accessed October 20, 2026. https://www.patrimonionacional.es/colecciones-reales/telas-medievales/almohada-de-la-reina-berenguela

Polliack, Meira. Karaite Judaism. Brill, 2003.

Sáenz-Badillos, Ángel. A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Sáenz-Badillos, Ángel, and Judit Targarona Borrás. Diccionario de autores judíos (Sefarad. Siglos X-XV). Ediciones El Almendro, 1988.

Scheindlin, Raymond. Wine, Women and Death. Medieval Hebrew Poems on the Good Life. The Jewish Publication Society, 1986.

Schippers, Arie. “Symmetry and Repetition as a Stylistic Ideal in Andalusian Poetry:

Moses ibn Ezra and Figures of Speech in the Arabic Tradition.” In Amsterdam Middle Eastern studies. Edited by Manfred Woidich. Reichert, 1990.

———. “Biblical and Koranic Quotations in Hebrew and Arabic Andalusian Poetry.” In “Ever” and “Arav,” Contacts between Arabic Literature and Jewish Literature in the Middle Ages and Modern Times. Edited by Yosef Tobi. Afikim, 2001.

Stillman, Yedida, Paula Sanders and Nasser Rabbat. “Ṭirāz.” In Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by Peri Bearman, Thierry Bianquis, Edmund Bosworth et al. Brill, 2000.

Waltson, Andrew. Agricultural Innovation in the Early Islamic World. Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Yellin, David. Theory of Spanish Poetry. Magnes Press, 1972 (1st ed. 1940) [Hebrew].

Author Bios

Emma Cusson is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Information Sciences at the École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information (Université de Montréal). She also holds a master’s degree in Religious Studies from the Institut d’études religieuses (Université de Montréal). Outside of her studies, she practices textile arts as a hobby.

Guadalupe González Diéguez is an associate professor at the Institut d'Études Religieuses de l'Université de Montréal (Canada). Trained in Jewish Studies (New York University, USA, PhD 2014) and in Hebrew Philology (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain, PhD 2016) she works on the intertwining of philosophy, mysticism, and literature in the intellectual production of Iberian Judaism, and the contacts among Jewish, Islamic, and Christian religious cultures in the Middle Ages.

Article Citation

Cusson, Emma, and Guadalupe González Diéguez. "Threads of Gold: Reclaiming the Textile in the Metaphors for Biblical Citations in Medieval Hebrew Literature." Corpus Textile, special issue of Fashion Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1-26. https://doi.org/10.38055/FCT040108

Copyright © 2025 Fashion Studies - All Rights Reserved

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license (see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)